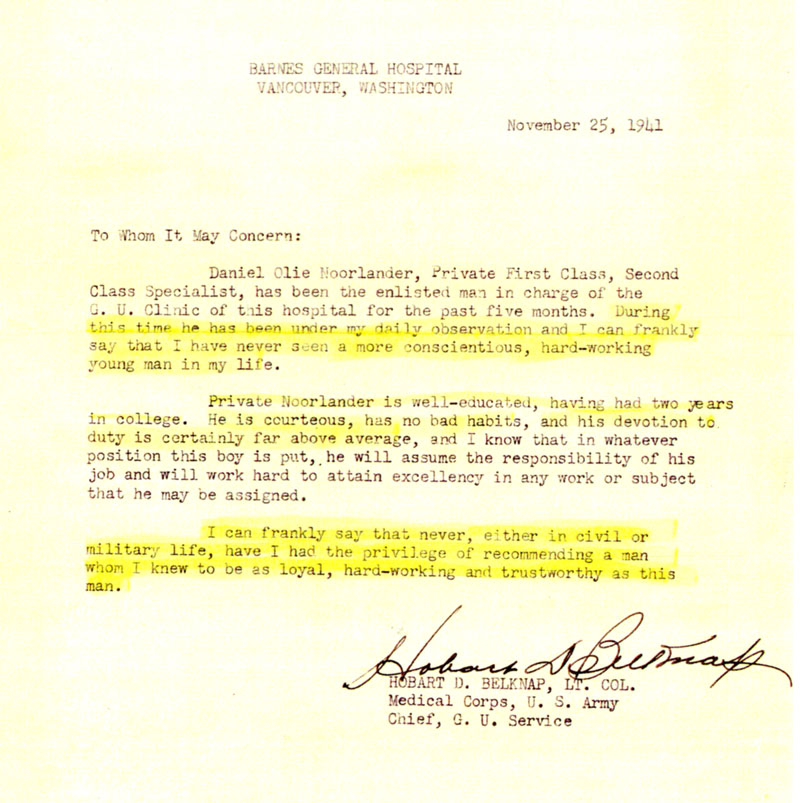

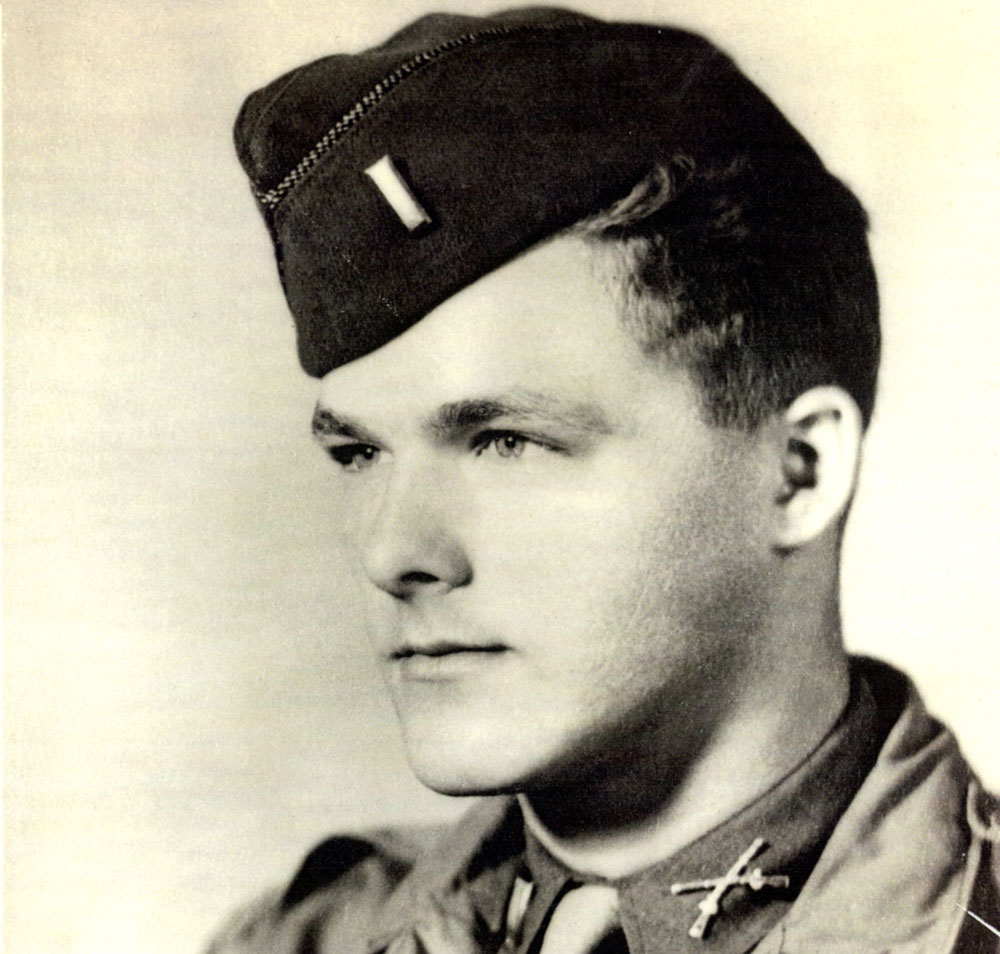

Lieutenant Dan Noorlander

March 12, 1921 — October 3, 1990

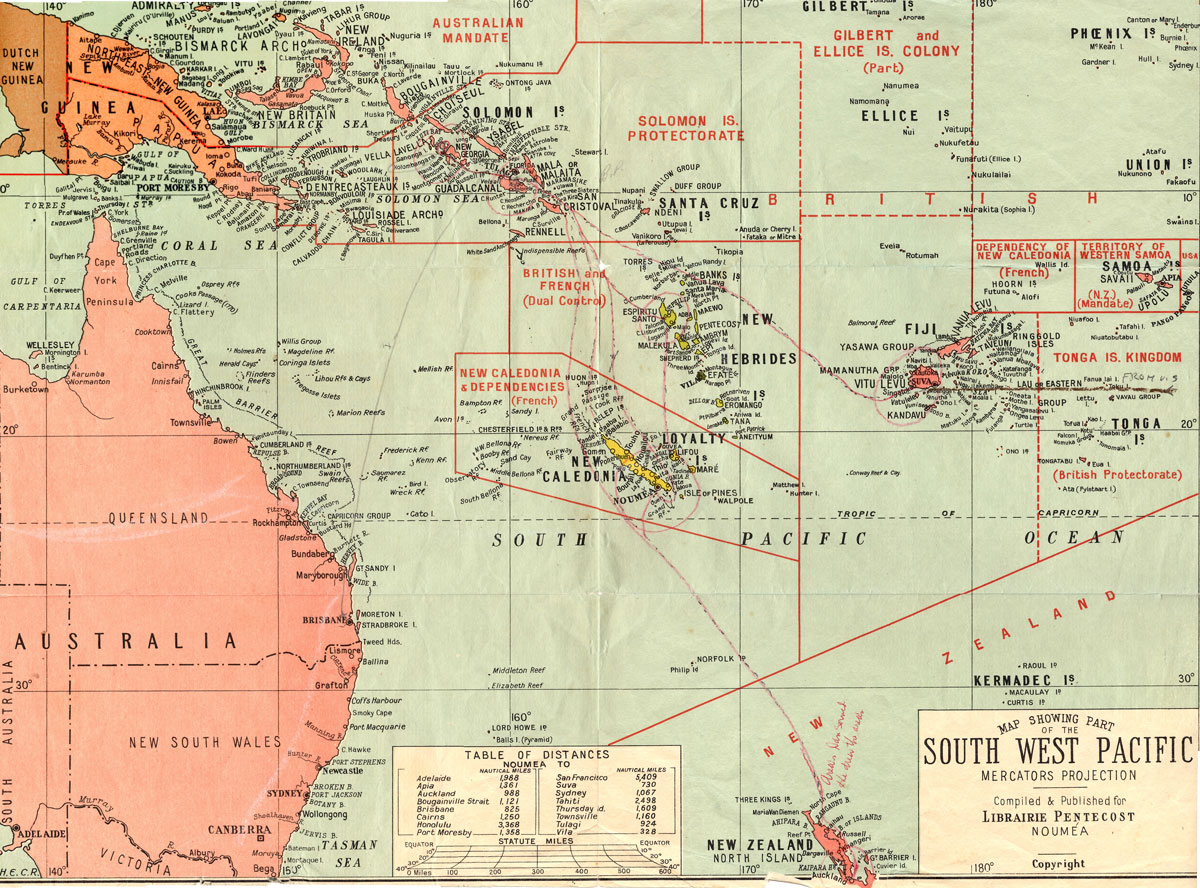

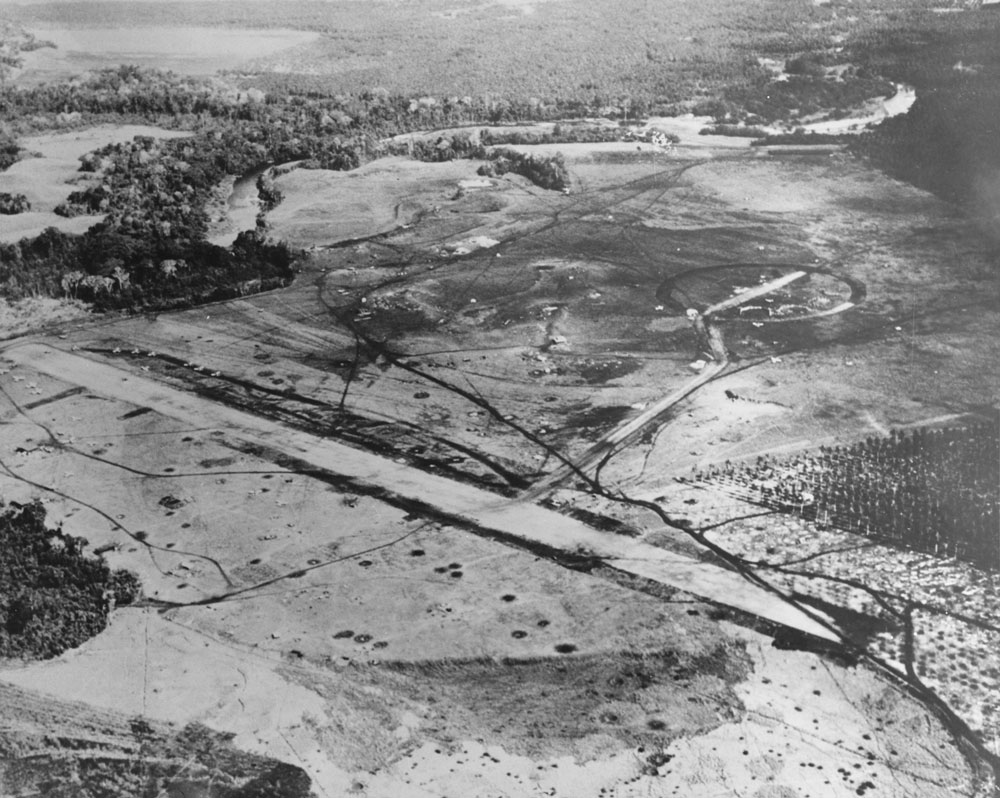

New Caledonia

The last months of Lt. Noorlander’s army career were spent on New Caledonia, away from the main action, where he used his considerable experience to train men for combat. Always the innovator, his ingenuity was put to the test several times, often under humorous circumstances.

Once again, Lt. Noorlander’s devotion to the men under him was on full display when he ran afoul of company officers who insisted that he use traditional but ineffective training methods. Lt. Noorlander refused, knowing that he couldn’t prepare the men using the time-consuming methods contained in the Army manual, and instead give them what they needed for combat.

Lt. Noorlander’s Account

Training Combat Troops — Going Home after 3½ Years in the South Pacific

The Island

New Caledonia was a former French prison colony where the population was divided between the descendants of the prisoners, Melanesians, and a labor force from Java to mine tin and other minerals.

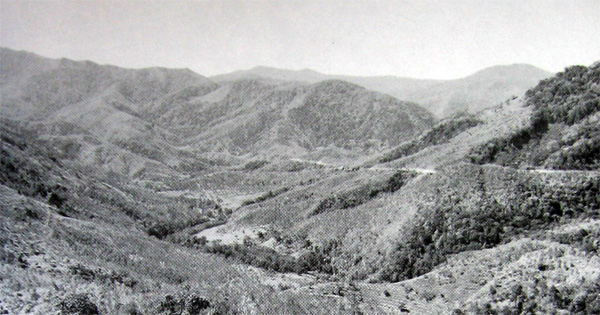

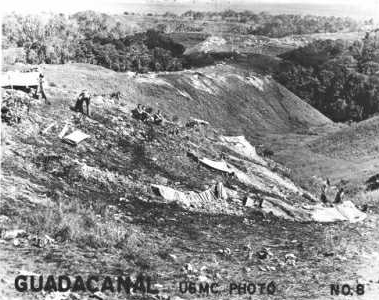

The north half of this hundred-mile-long Island was tropical like Guadalcanal, but the southern half was more like Southern California. It was ideally suited for training soldiers and for regrouping combat troops. It was also a good place for the Army to send all its misfits and reclassified Army officers who couldn’t quite make it in combat, but who couldn’t do much harm since the enemy was far to the north.

New Caledonia with typical terrain.

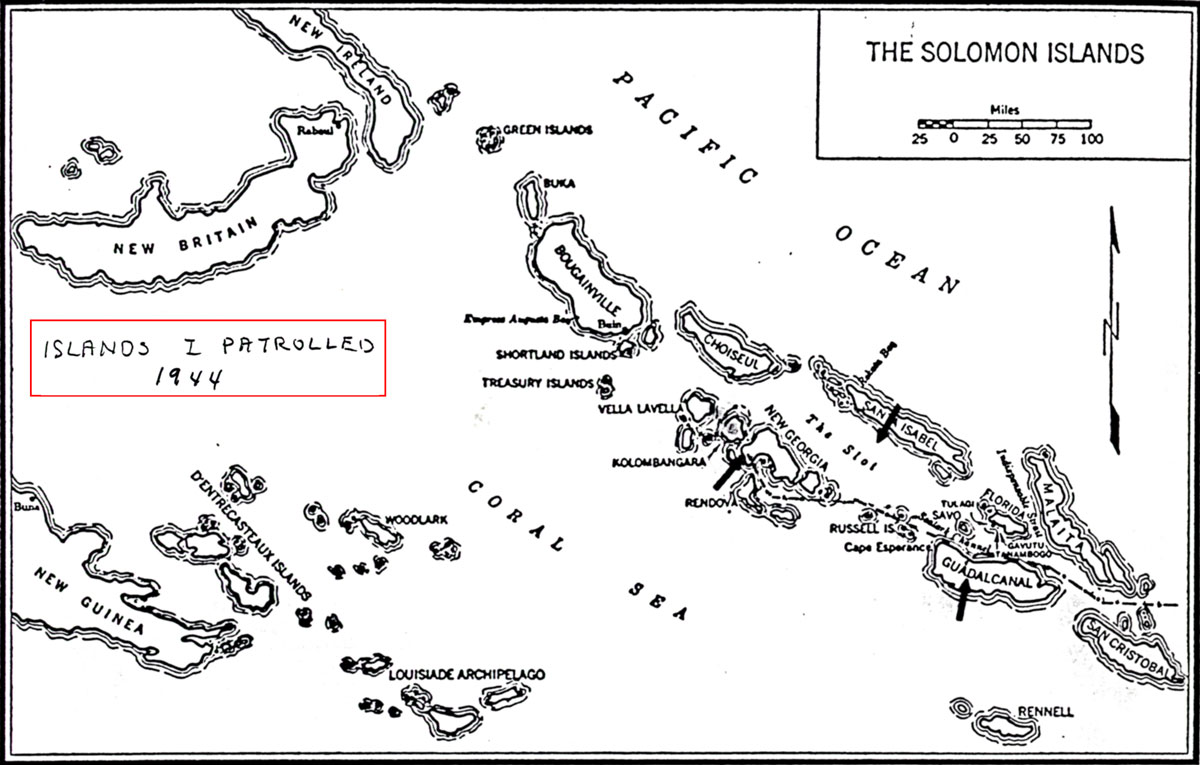

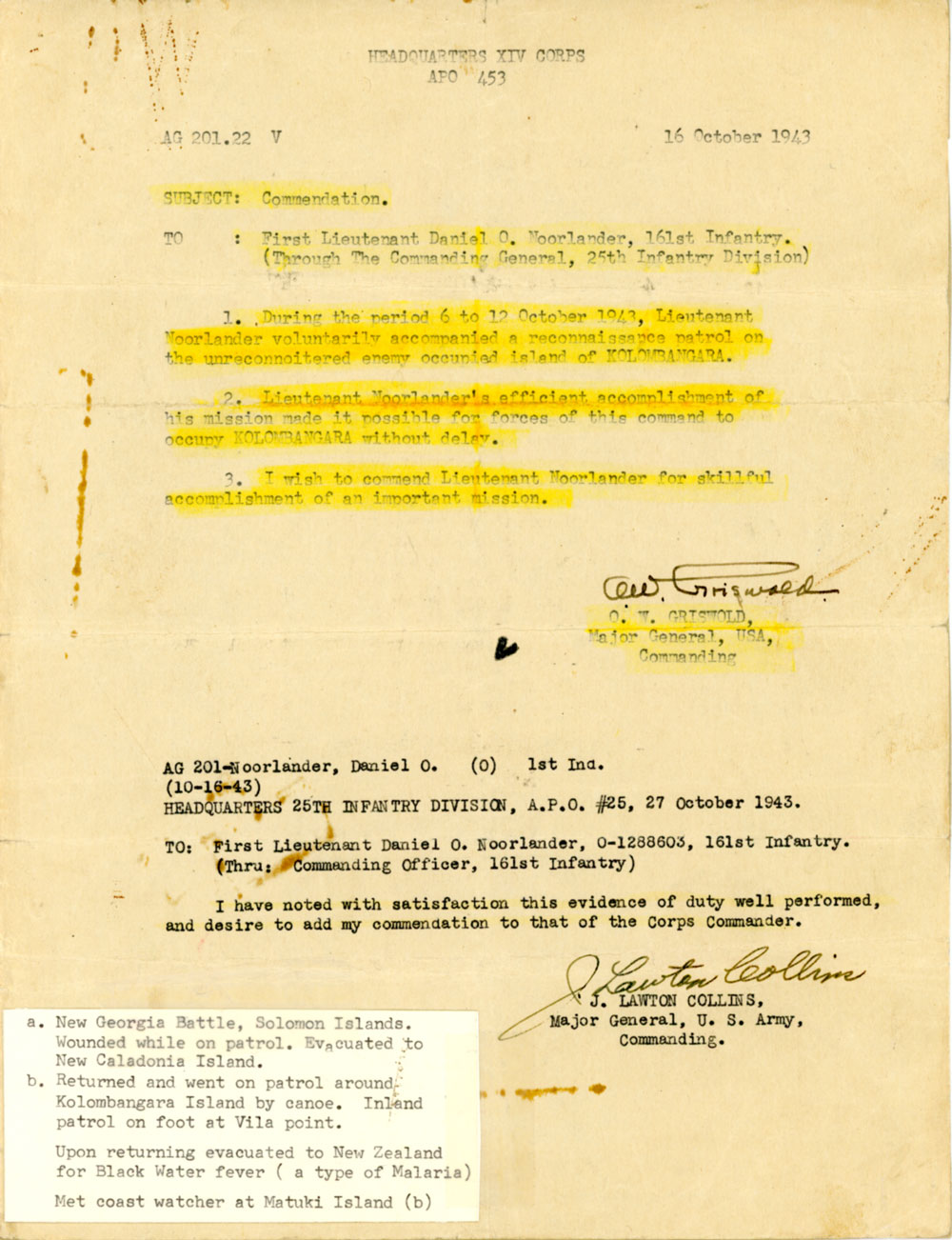

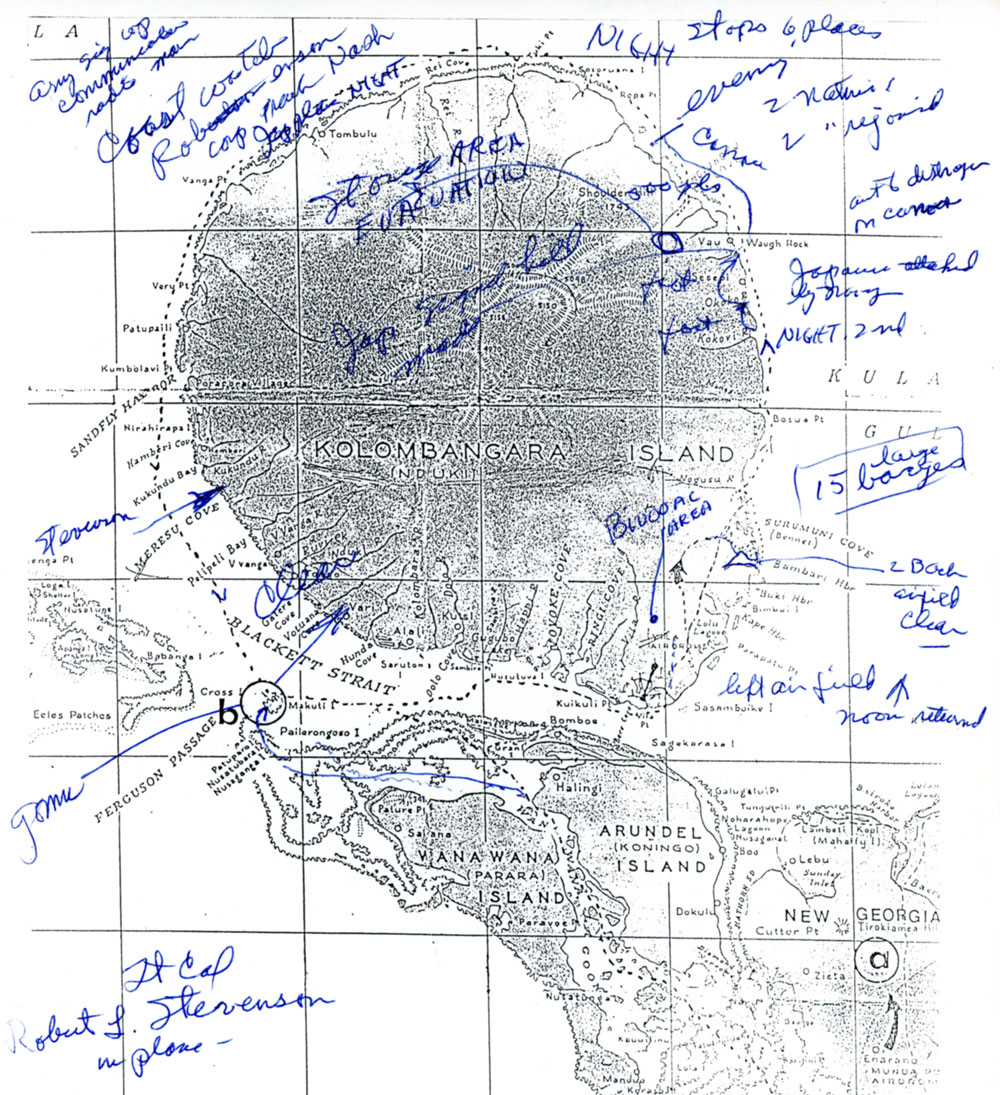

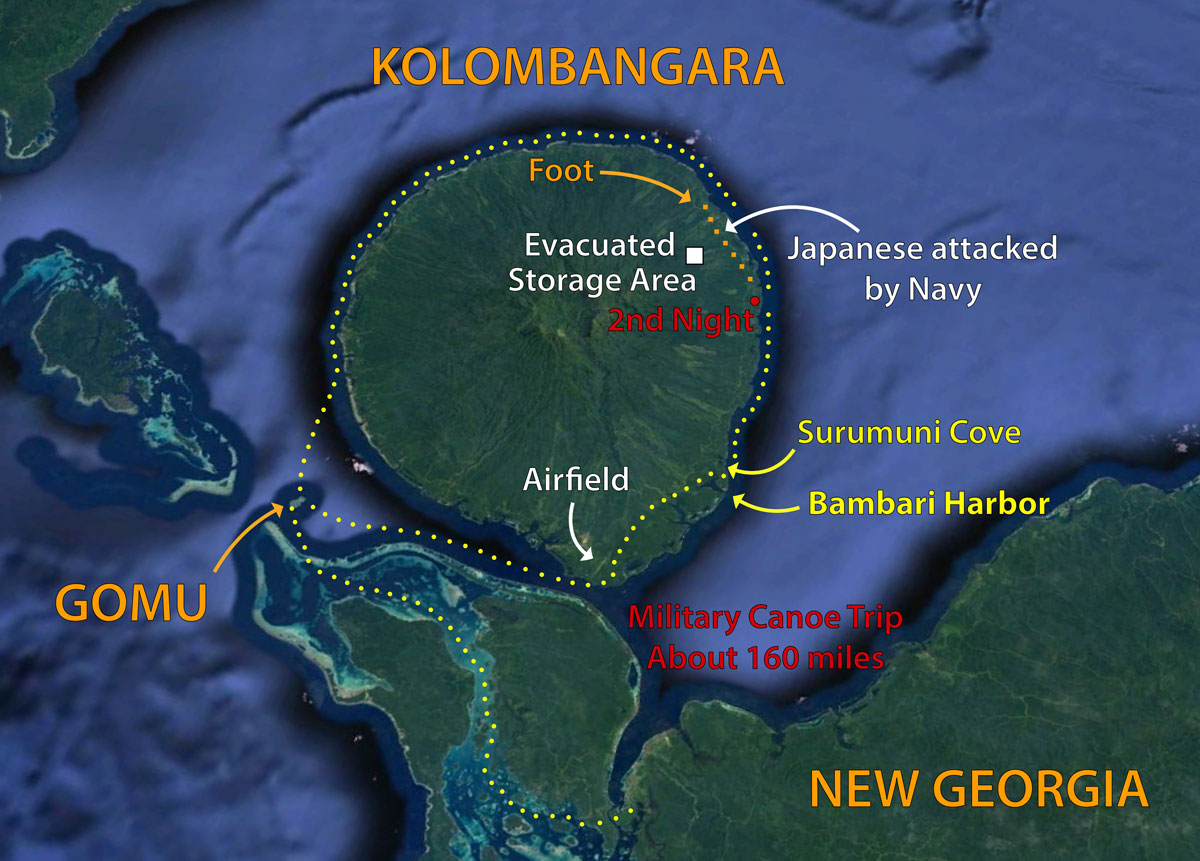

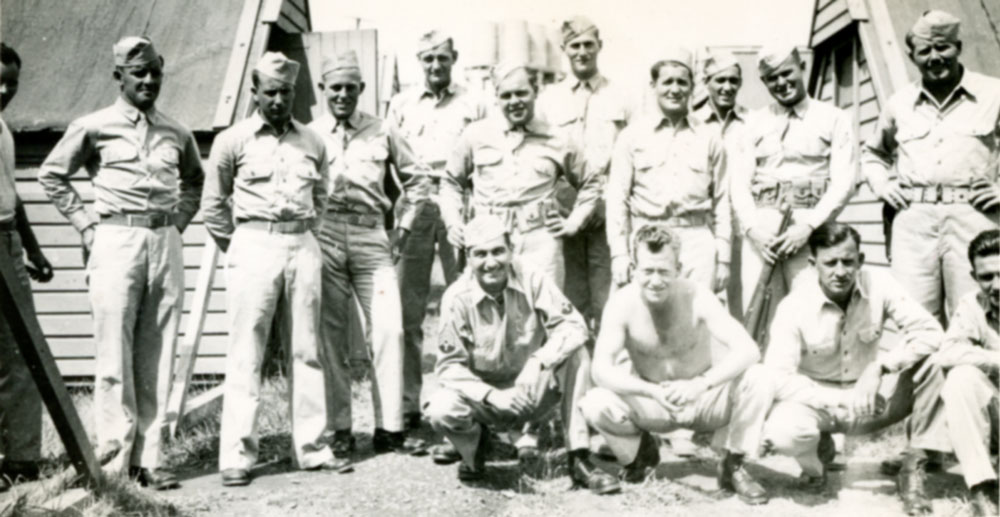

I lived on the Island three times: Once I was evacuated there from New Georgia after I was wounded. I was there this time as a platoon leader assigned to the 25th Division Reconnaissance troops. The division was headed by Captain Ferriter, who went with me on patrol around Kolombangara. The final time I was sent there as a training officer for soldiers being reassigned from the European theaters to fight the Japanese.

Assignments

One of my assignments was to take my platoon and make a reconnaissance of a small offshore island just north of the Noumea Harbor, which became a major port for our Navy. The division wanted to map the Island in preparation for some maneuvers.

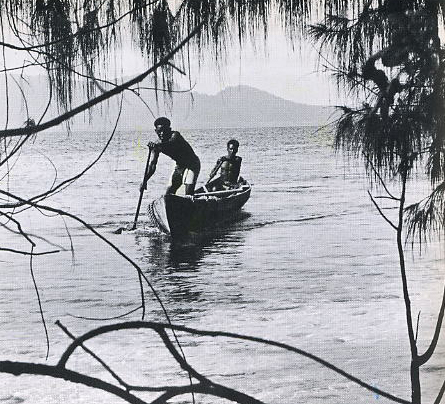

New Caledonia with small island north of Noumea Harbor.

After landing on the Island, we were inundated with millions of mosquitoes, which covered everyone’s back as we hunched over to avoid being covered completely. The tall, dry grass that covered the Island didn’t do much to discourage the mosquitoes, and I couldn’t see how any soldier could possibly learn anything there, but the operation was already in the works. The division troops were going to land on this mile-long Island in just three days.

I tried to figure in my mind just how I could explain to a division commander that it was going to be impossible to use the Island for maneuvers because of some mosquitoes. I couldn’t even map the Island, because I couldn’t take my hands out of my pockets long enough to hold a pencil.

Necessity finally took over my thoughts, and I figured either the mosquitoes were going to win out or something else more dramatic would have to take place. I called my troops over in a huddle and made a suggestion: “See all that dry grass? It looks like it covers the whole Island.” Then, I asked them if they thought it would burn. “Yeah, if we don’t go up with it,” my sergeant added.

I remembered a little about firefighting techniques in California during the dry season when firemen used “backfires” to control a blaze. “What do you say we split up in two groups, with each group going around the Island and setting fire at the shoreline and having the fire work itself toward the middle?” I asked.

The plan seemed plausible, so we proceeded to set fire to the tall, thick, dry grass. What resulted was not just an ordinary fire. If hell was anything like it, I didn’t want to go there.

It seemed as if the grass was saturated with oil, because as it reached its height in the middle of the Island, it looked like an active volcano. The smoke became so dense it covered Noumea Harbor and every ship in the Navy. I became a little concerned. Nevertheless, as I mapped the Island, not one mosquito bothered me.

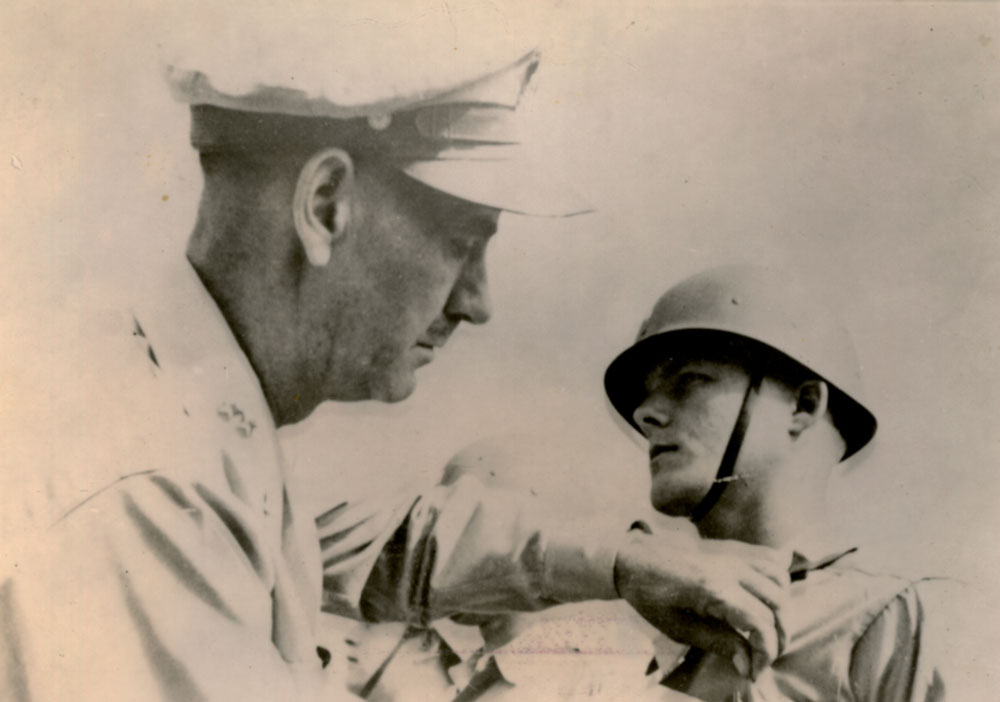

Captain Ferriter

When I returned later to company headquarters, Dick Ferriter walked over to me and asked me in rather subdued tones, “Just what went on over there? The Navy has been bugging division headquarters for an explanation, and the Army has been wondering if the Navy had some special maneuvers out there it wasn’t aware of.”

“Well, as long as they think each other did it, no damage has been done,” I said, as I tried to smooth things over. Captain Ferriter responded, “If you won’t tell I won’t.”

Captain Ferriter covered me on several other occasions, as I attempted to occupy my boredom. On one occasion I tried out a new method for discharging bazooka shells that I read about in an Army manual. Instead of firing the shells through a tube, it recommended placing the shell in the crevice of a V-shaped board nailed together, similar to what you might do setting up traps for tanks. I thought I would try it out and had my platoon make a half dozen V-shaped boards for a trial test. When the shells were inserted in the channels, I angled them for maximum distance and fired them with an electrical charge from a battery.

It worked, and they did look beautiful as they arched into the sky about a mile from where we stood. It was just like the Fourth of July. Nevertheless, it didn’t take long for me to realize that the result was just like the fire we started on the small island north of Noumea Harbor. Although the grass under the trees was not as tall, it was dry. It caught fire as the bazooka shells exploded. The whole company was called out on this one, with every man grabbing available shovels and water.

Later, a tired company was black with soot as they stood in line at retreat. I looked at Captain Ferriter out of the corner of my eye. He kind of smiled as he shook his head, and I guess he wondered what kind of a platoon leader he had. I was glad he didn’t find out that I was responsible for a major scare on the Island just a few weeks later.

Flare Pistols

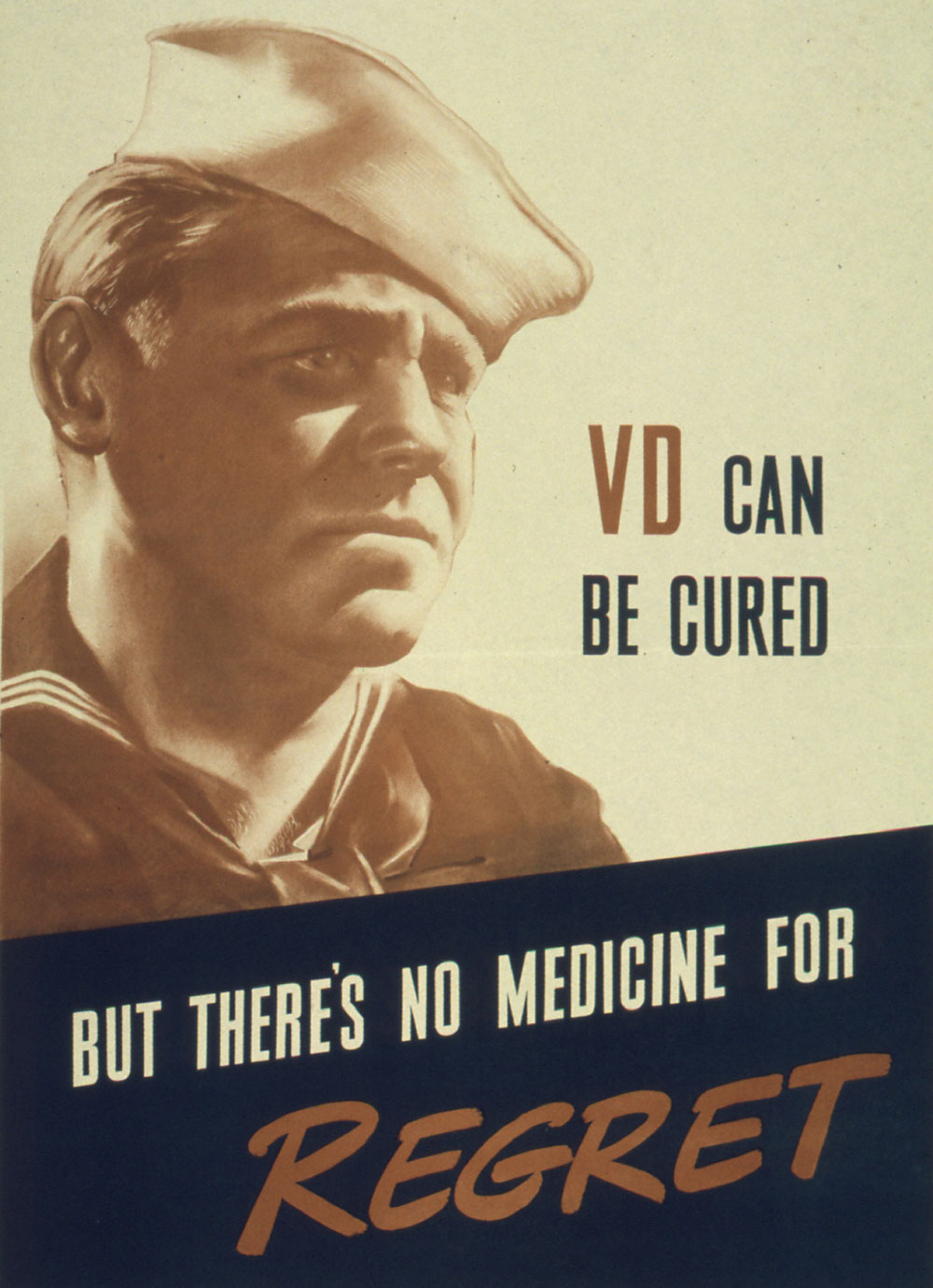

I was working on a project to develop a simple flare that could be shot from a flare pistol. Flare ammunition was almost impossible to get, and I remembered the times on Guadalcanal when I wished I had some.

I fussed around with some tracer ammunition. I took out some of the black powder, then placed it in the wooden chamber I made and placed in the large chamber of the pistol. I found the tracer ammunition would spin out of the pistol like a Fourth of July spinning wheel. Each tracer had a tail about six inches long, which lit up the night.

I made up about 50 of them and decided to fire them as a test somewhere away from observing eyes, in case something went wrong. On the way to Noumea I decided to fire some into the air to see how far up they would go. I gave half of them to one of my squad leaders following behind me in another jeep. The flares worked perfectly. Both of us caught the spirit of the thing and started to whoop it up as we fired cowboy-style down the road. Just then I noticed a wire fence to my left that had unusual piles or stacks of something that lit up under the light of the red flares. I ducked my head and waved to my sergeant to cool it, but he had already grasped our situation. What we had exposed with our flares was the Island ammunition dump.

We both put our jeeps into gear, and got out of there fast. Fortunately, the Army had cleared the grass from around the stacks of munitions, and my men played dumb when news came out about the strange happenings the night before: “The ammunition dump was raided by unknown parties.”

Training Command

About three months later I was given a physical, including an eye check. It was found that my right eye had a blind spot in the center of vision, and I was reclassified so I couldn’t go into combat again. In later years I was able to hide this defect by memorizing the letters in a doctor’s office when I was preparing to go to Korea. While on New Caledonia, I was assigned to a training command to teach soldiers how to fire weapons. I found out later that I was the only combat officer on the training team.

How to Get Blackballed

My new commander asked me to set up a training program for the new soldiers coming in from Europe. They were, for the most part, former medics and service troops that the Army wanted to train as infantry soldiers.

Having been in combat and realizing that I had these soldiers for only two weeks, I decided to give them the information and training they would need to kill the enemy and save their own lives in battle.

Instead of giving them time-consuming training methods from the Army manual, all new soldiers learned how to fire every infantry weapon from the hip, including machine guns and rifle grenades. We also dropped grenades in front of them with only a mound of dirt to protect them from the shrapnel. The trainees fired their rifles at moving targets, as they got used to the noise of battle. We had the men cross a river on oil-drum bridges tied together with strips that were used on landing fields. After all was said and done, we were able to move several hundred soldiers through each two-week training cycle.

Placed Under Arrest

After one such exercise, I rode from the river on top of a truck filled with oil drums to get ready for the next class. I was met by the commanding officer who proceeded to reprimand me.

The commanding officer was a Captain who did not take kindly to my methods of training. I was getting some attention because of my methods, which turned service personnel into soldiers in the shortest possible time. The Captain called me into his office and ordered me to stick to more conventional methods of training. After a slightly heated exchange, and recognizing his real intent, I told him where he could go. He ordered me to my quarters and placed me under arrest.

A few days later I was confronted by the Island Commander. I tried to explain my position, but he would have none of it. He said he was going to give me a general court martial.

“Colonel, that’s just what I want. And let me tell you one more thing. I want a General to find out how you ordered me to train troops to go into combat without giving them with the necessary training to protect themselves, let alone kill the enemy. Now isn’t that the function of the army,” I asked with a delayed “Sir.” I continued, “Your Captain knew what we were doing and accomplishing before ordering me to stop the training.”

I reinforced my attack by adding that every man I trained cost the citizens of the United States thousands of dollars just to get them here. It was a hard cold fact of life that when a man was killed, it cost the taxpayers another $10,000 for insurance claims alone. Then I asked the magic question, “Sir, how would you like me to expose this situation to my congressman?”

The Colonel was taken back so completely that he didn’t know what to say. When I added that it did not make any difference to me if my commission was taken away, because I would prefer to fight the Japanese as a Private than put up with Army stupidity. He ordered me to my quarters, and placed me under house arrest (again).

I had two things going for me if I didn’t plan to make the Army my career. First, my war record contained two medals and a citation; and second, I was the only combat officer in the training camp. I also knew that these rear area commanders would be on the front line if they had anything on the ball at all.

Without Conscience

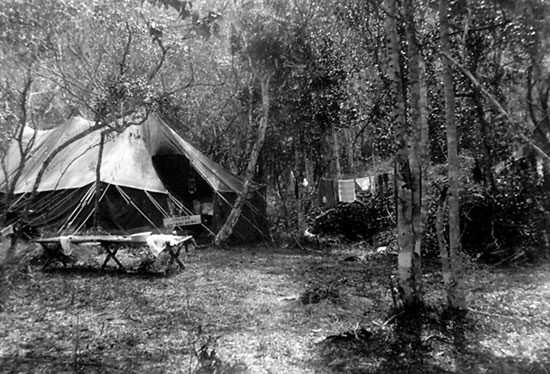

After a week of confinement in my tent, the Army Adjutant General came to see me. He was kind of an Army attorney. He asked me to sign a paper that I had been insubordinate to my commanding officer. I refused. “No,” I said. “I think I would rather have a court martial.”

New Caledonia 1942. Army tent with folding cot.

He came back the second day and the third with the same request. I gave him the same answer both times. Since I refused, he decided to use another approach.

“Lieutenant,” he said slowly, “the word is out about your case here, and it is spreading all over the Island. It is now a problem of discipline among the soldiers. I am appealing to you Lieutenant. Increasingly, it is becoming an embarrassment to the Colonel. Please sign it.” He softened his position by informing me that the letter I was to sign “only says that you used ‘harsh’ words against the Captain,” adding that if I would sign it, he would drop the court martial.

“And if I don’t?” I asked.

Without hesitating he said, “You will be blackballed.”

“What do you mean by being blackballed?”

Without any display of emotion or feeling of guilt, the Adjutant General answered very simply, “You will be transferred to a small Island, and no one will ever hear of you again.”

At that point I figured that I had no alternative. I learned for myself that sometimes an Army soldier is not protected by the natural right to life guaranteed him by the Constitution of the United States.

New Assignment

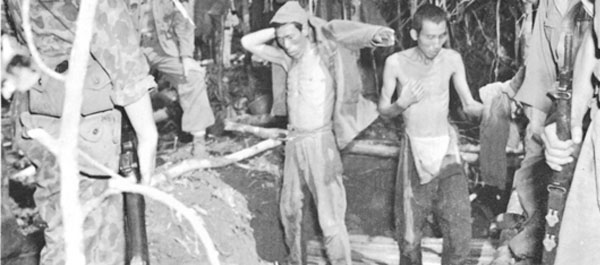

I signed the paper and was assigned to an Island that had already been abandoned. I ended up on Guadalcanal with the Military Police. My job on the island was to crack down on stills used to make raisin alcohol. There was no legal basis to prevent the men from making moonshine, but a soldier could be tried for using Army property. I did find a lot of stills, but never made an arrest.

I knew a lot of the Melanesian natives on Guadalcanal, and only had to ask if they knew where the GIs were making moonshine. I’d wait until the mash was just about ready, dump it, and then get the word out that there was going to be a raid that night. The soldiers, of course, never showed.

I felt pretty good about not marring the service record of a few bored soldiers, especially when I knew that the commissioned officers were allowed three bottles of whiskey, rum, or brandy every month or so from what was called the liquor locker.

Because I didn’t drink, I gave my allotment to the men who did drink. I reserved some of it for a special time, such as a birthday. This way it was spread around without damage to anyone in particular. I rationalized that good American-made whiskey was better for the men than the rot-gut some of the soldiers resorted to, which was often purchased or made of commodities that contained lead, gasoline, and even wood alcohol.

Rest and Recuperation

I did feel that I would like to get away from the Islands for a while and had the opportunity to fly to New Zealand on what was called a “chicken run” for supplies. When I made a formal request through channels, it was turned down.

I submitted another letter, this time telling the commanding officer that I was going on a vacation into the hills to do a little fishing. He sent a “shrink” to find out if my head was screwed on right. When confronted, I told the shrink my story. He said that he didn’t blame me. He also told me that the Commander’s only reason for not permitting me to go was that he didn’t want to set a precedent.

I showed him my record, indicating that I had more time in grade, more time overseas, and more combat time than any other soldier on Guadalcanal. I added that Army regulations provided for “rest and recuperation time” based on a point system, and that I had more points than anyone there. I had not been kidding him. I was packed and ready to head for the hills where I knew I had some friends.

I was finally sent back to the United States for “rest and recuperation.” The trip back home was not very eventful. Someone in the Navy confiscated the souvenirs I had in my locker, which included a pistol, a sword, and a flag from Kolombangara. The items probably brought some sailor a good price.

When the ship sailed under the San Francisco bridge, the speaker started to play “Oh What a Beautiful Morning.” Even with the fog it sounded really nice as an Army band greeted the ship. After leaving the ship we headed home by train. As I reached into the overhead racks to stow my luggage, my wallet was stolen from my back pocket. I felt someone brush passed me, so I’m pretty sure that’s when he lifted my wallet. I lost over $300. It happened all the time to soldiers on trains because they were usually carrying their last months pay after being discharged.

I wondered to myself, what was I doing fighting the Japanese with people like that wandering around!

Going Home

While I was on my first “rest and recuperation” in over 3½ years, the atomic bomb was exploded over Japan. As a result, I did not have to return to the Islands as originally ordered.

After the Army I went back to school to finish my degree in agriculture. I was destined to help resolve one of the most serious dairy cattle diseases in veterinary medicine, and most costly to the dairy industry. Mastitis is a disease of the mammary gland, usually precipitated by mechanical milking.

My insights into problems of the dairy cow led me to many nations of the world. I eventually ended up in Guatemala as an agricultural missionary for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. It was an event that opened my eyes to the real struggle for human survival, similar to the reason I had to fight the Japanese in World War II, and the Chinese in North Korea.

Lt. Noorlander as a missionary in 1973, standing with Brother and Sister Cujcuj in Patsun, Guatemala.

.jpg)

;

;