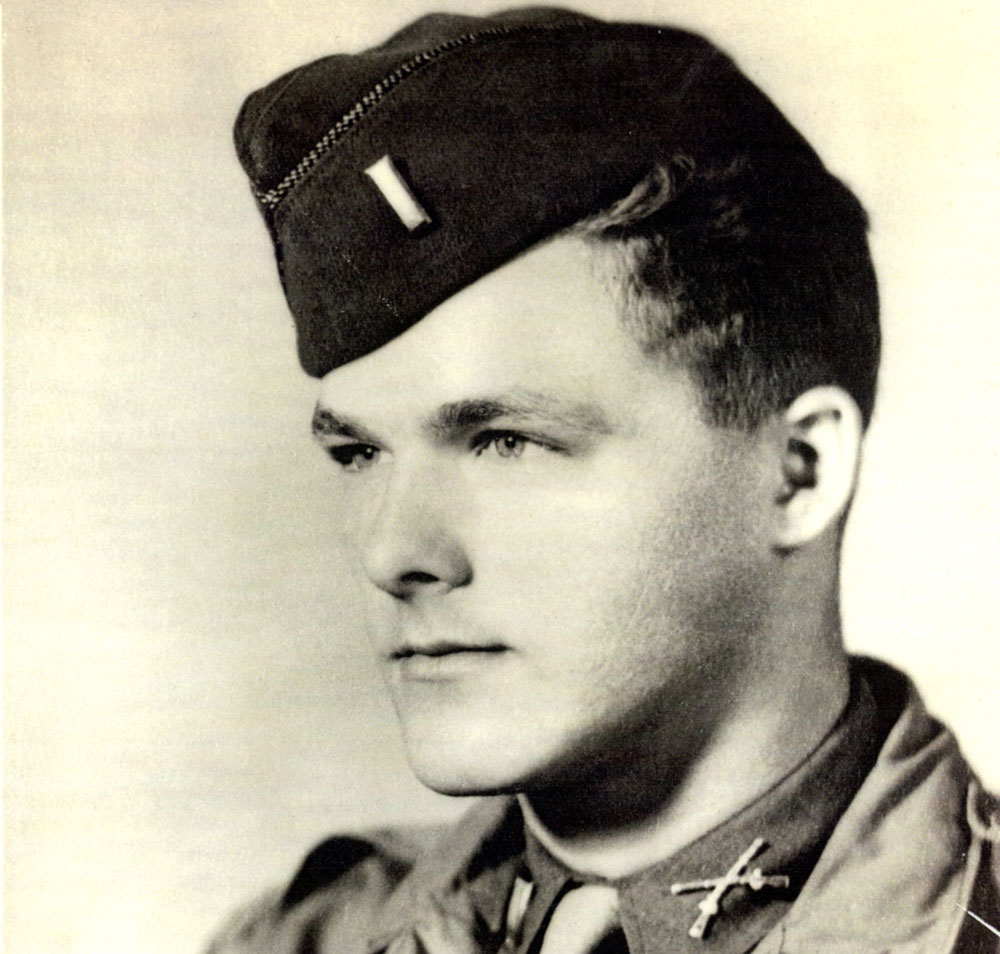

Lieutenant Dan Noorlander

March 12, 1921 — October 3, 1990

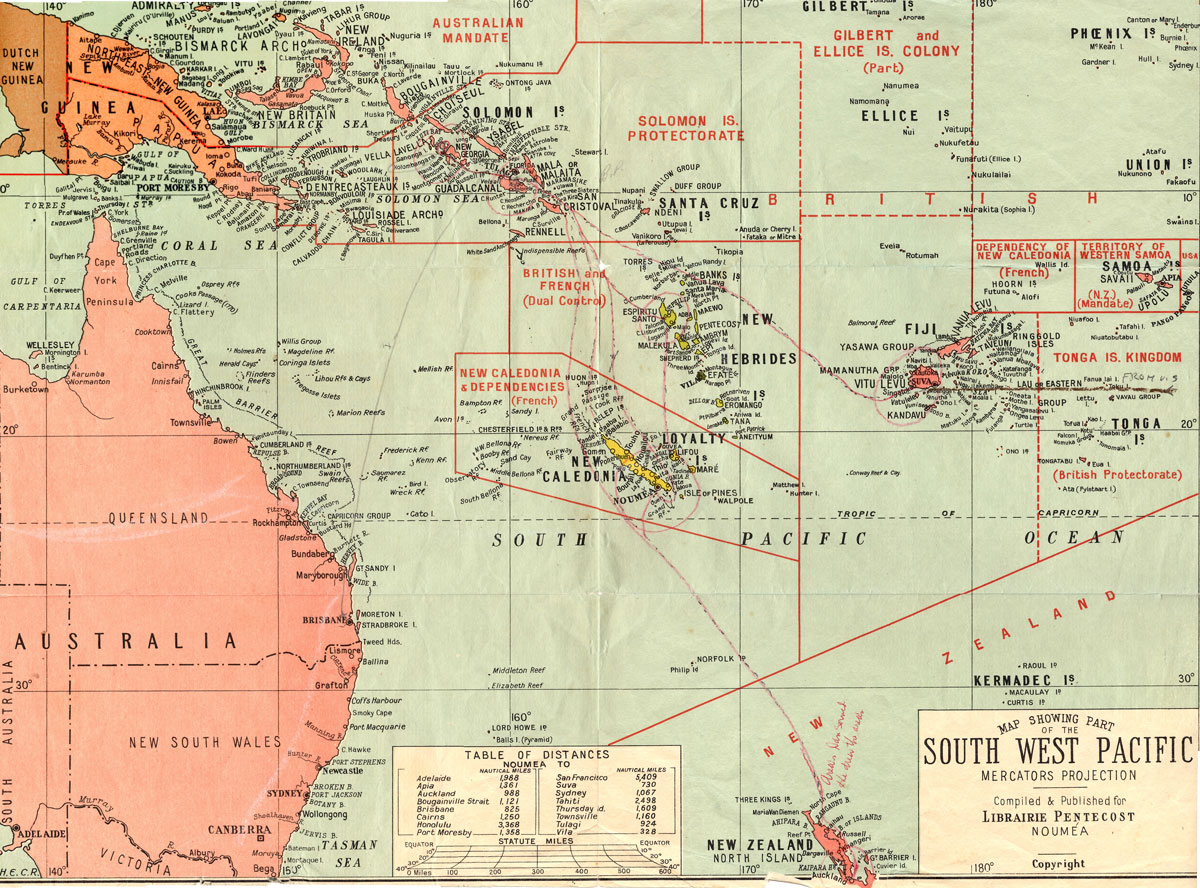

Hawaii

Before Infantry School, Lt. Noorlander served as a medic in Vancouver, Washington, where he decided that being a male nurse was not for him.

After Infantry School, he left Ft. Benning, Georgia, to continue training in Hawaii with the 25th Army Division.

Lt. Noorlander’s platoon was assigned to protect a half mile stretch of Oahu’s northern shore in case of a Japanese landing.

Lt. Noorlander’s Account

Declining a MASH Unit in Europe to Carry a Rifle in the South Pacific

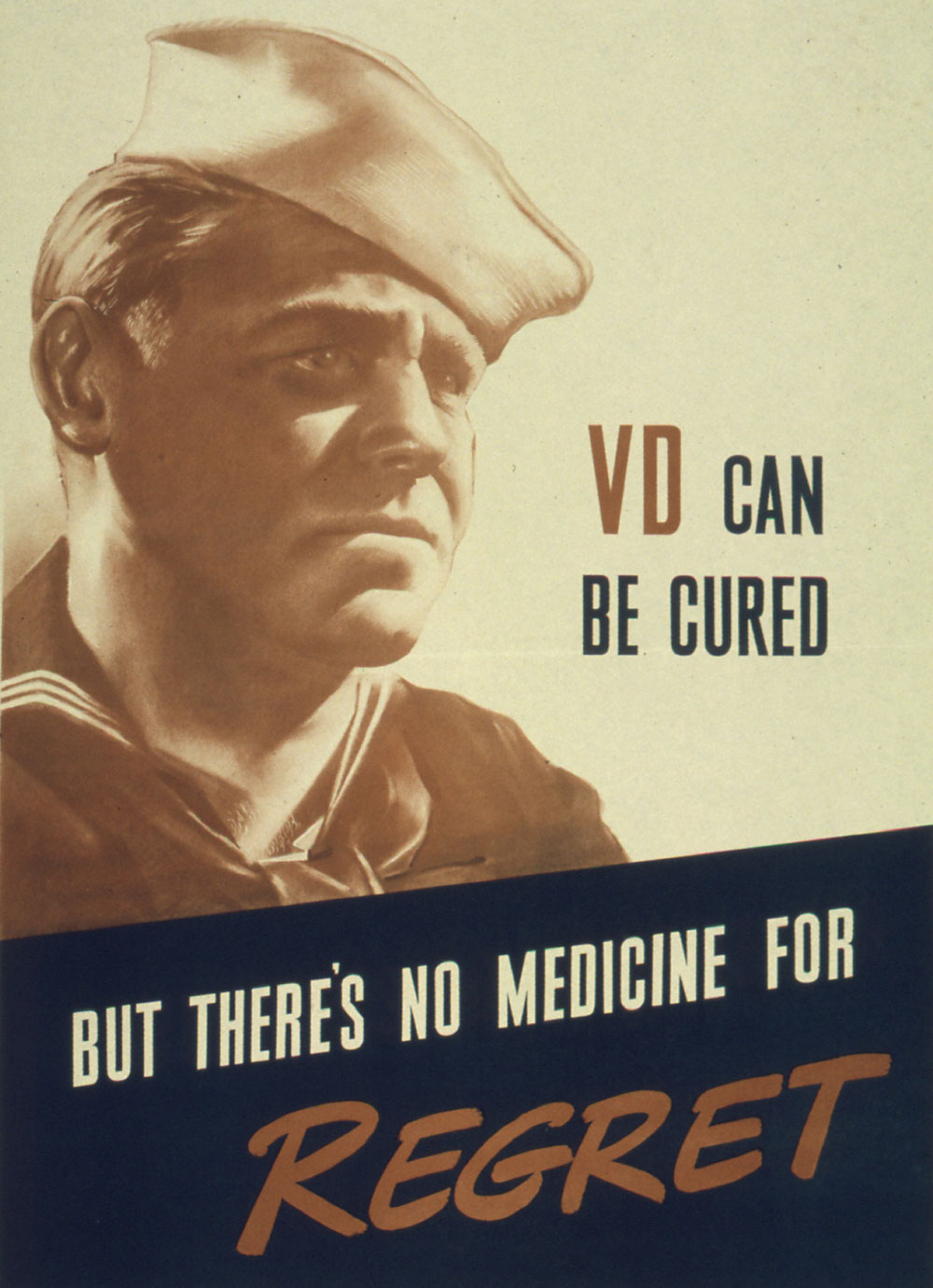

Medical Technician

My first hitch in the army was not all bad. Because I had some formal training in pre-veterinary medicine, I was assigned to Barnes General Hospital and was paid $21 dollars a month as a buck private. For the first few months I cleaned bed pans, made beds, and eventually become a medical technician in the genital-urinary clinic where I treated venereal patients for gonorrhea and syphilis. This was prior to penicillin and other wonder drugs and was not a pleasant task.

Barnes General Hospital, Vancouver WA

When infected soldiers came to the clinic for their routine shots of arsenic compounds for syphilis, I instructed them to take the assumed position so I could insert the large needle into their buttocks. I could feel the needle penetrate the many pockets of scar tissue from previous injections.

It was the treatment of gonorrhea that really got to me. I would have to irrigate an infected penis with potassium permanganate. The process stained the urinal dark brown, which I also had to clean. Rubber gloves did not make the job any less repulsive. Some soldiers were admitted with a penis so infected, they had to be rushed to the operating room where their tightened and swollen foreskin was literally slit open so a catheter could be inserted before draining their bladder.

It was the treatment of gonorrhea that really got to me. I would have to irrigate an infected penis with potassium permanganate. The process stained the urinal dark brown, which I also had to clean. Rubber gloves did not make the job any less repulsive. Some soldiers were admitted with a penis so infected, they had to be rushed to the operating room where their tightened and swollen foreskin was literally slit open so a catheter could be inserted before draining their bladder.

As I observed this daily routine and the misery and pain that went with it, I remember saying to myself: “What a price to pay” for a night of what the soldiers referred to as ‘poontang.’ Even in the barracks where I slept, sex appeared to preoccupy their minds. I wondered at times, how in the world we were going to win the war in front of us if this was the army’s preoccupation.

Transfer Request

On days off, I would pass the local Army post where the infantry could be seen training with their rifles and bayonets. They were training for combat. Pearl Harbor had been bombed and the medical teams were being formed for overseas duty. Nevertheless, I longed to be with those carrying a rifle. I was just not cut out to be a male nurse, so I asked for a transfer.

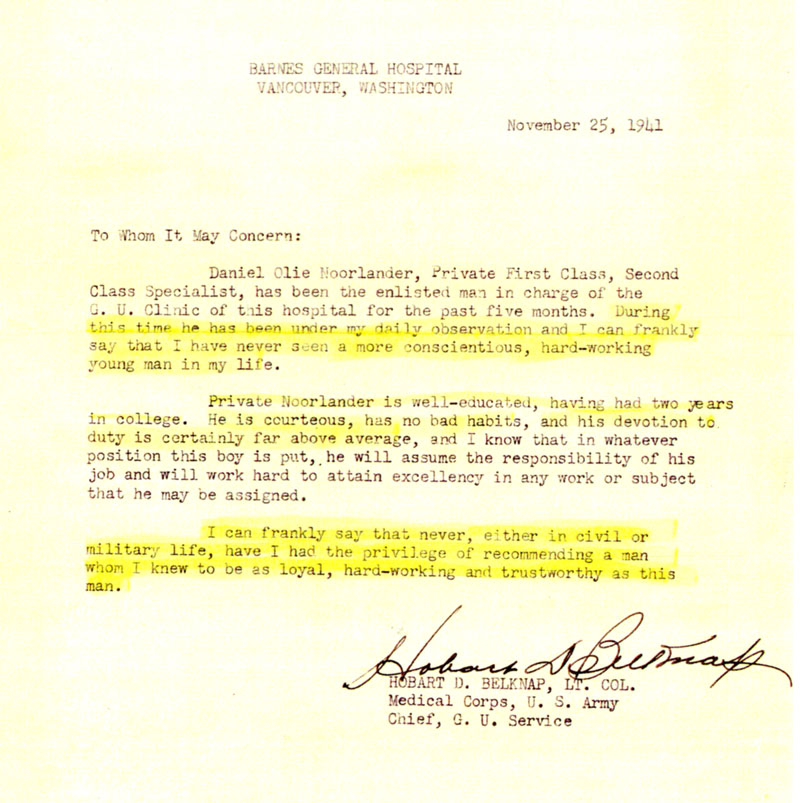

Colonel Belknap died April 2, 1971. He is buried in the Arlington National Cemetery, Arlington, VA. Plot: Section 4 Grave 3263-RH.

My boss, Colonel Belknap, was a reactivated army medic who took me under his wing. He called me into his office after learning about my transfer request. He told me that he wanted me to go to the European theater of operations with him as a member of his MASH team.

I told him that I felt my destiny was with the infantry, and that I would appreciate any help he could give me to get there. I explained that when I joined up, I had no idea that I would be sent to a medical hospital.

“OK”, he responded. “But if you want to get in the infantry, may I suggest that you apply for the Infantry School as an officer candidate.”

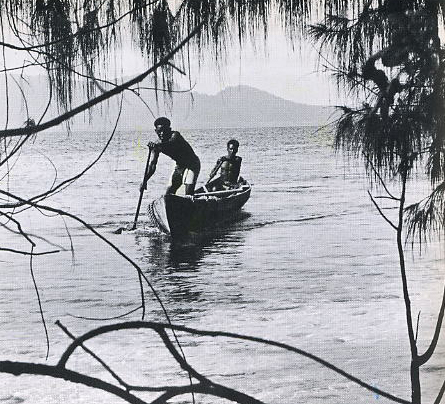

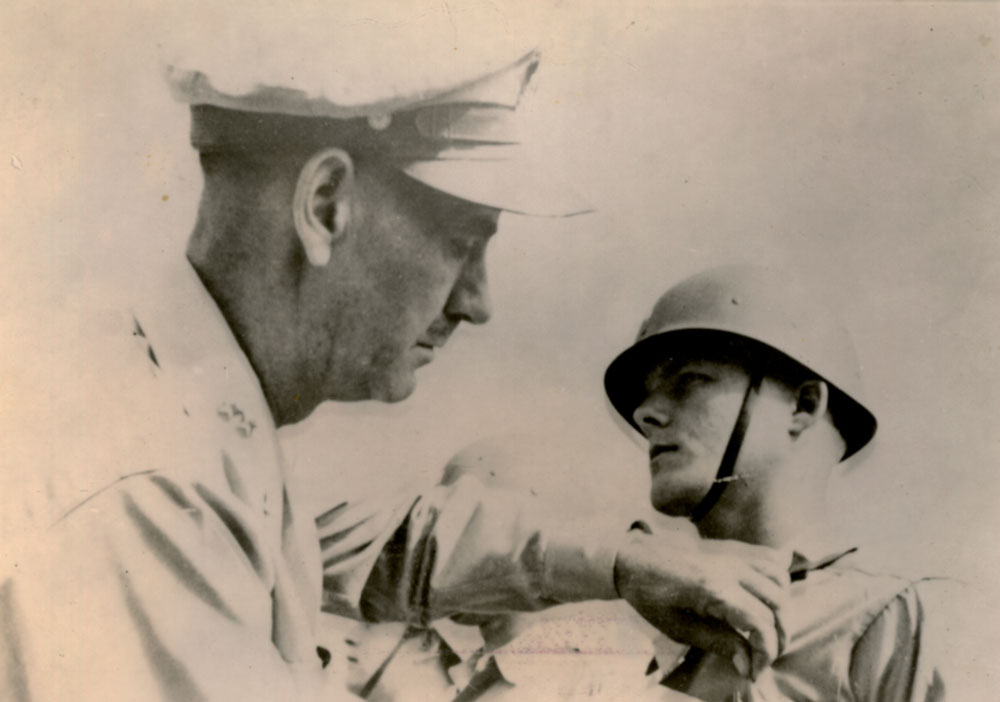

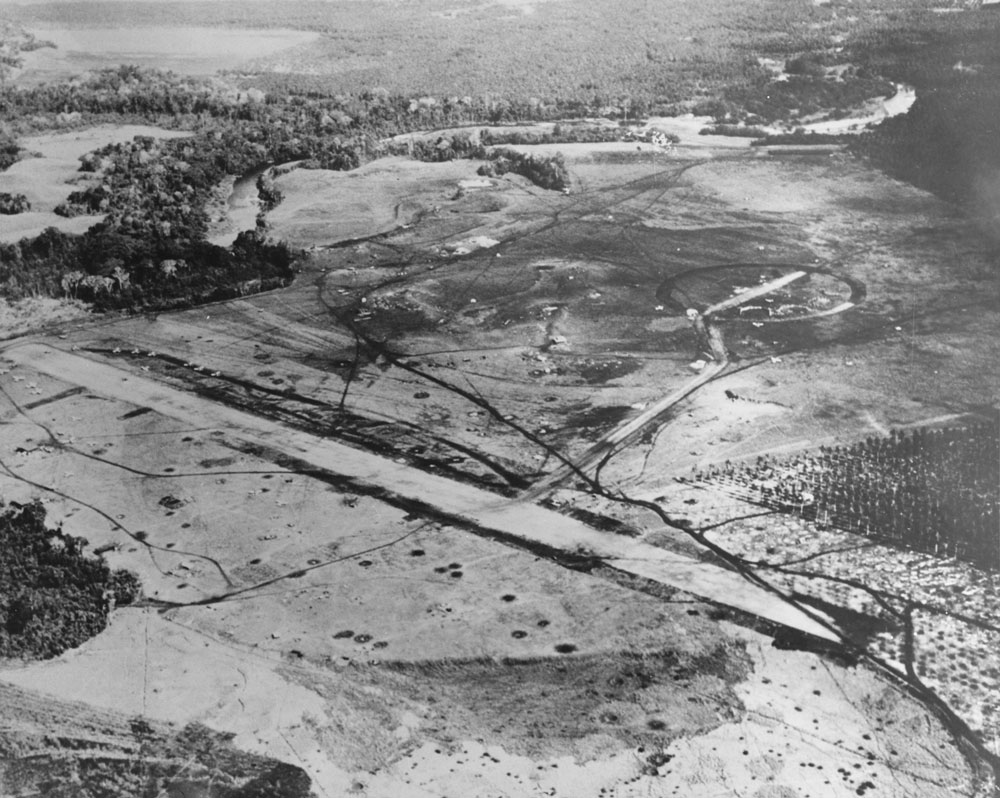

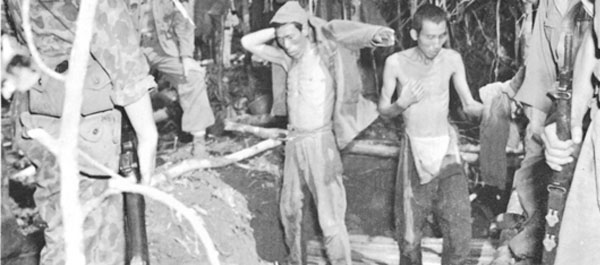

Infantry soldier on New Georgia Island, where Lt. Noorlander served. Notice the soldier in the background looking for snipers. Consider that Lt. Noorlander enlisted in the Army, choosing this life over a medical career as the best way he could serve his country in two major wars.

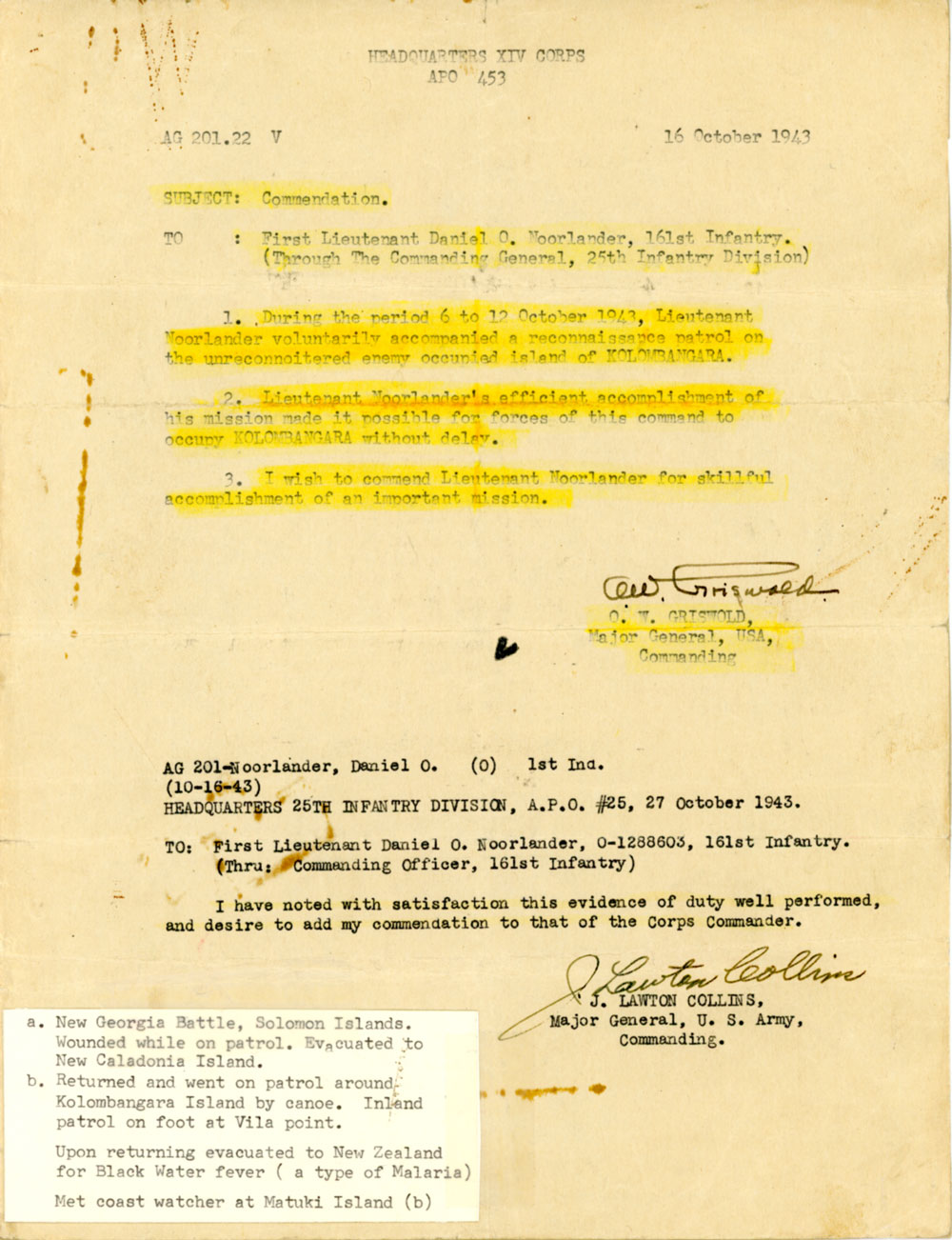

I found out that I would have to wait a few weeks to be eligible for a commission after I graduated, because an officer had to be 21 years of age. I was still 20. Not only that, the Infantry School only accepted non-commissioned officers. I was a fifth class technician. So, for a few weeks, I wore corporal stripes, thanks to the efforts of Colonel Belknap. His letter of recommendation was surely instrumental in my being accepted. He wrote:

To Whom It May Concern;

Daniel Olie Noorlander, Private First Class, Second Class Specialist, has been the enlisted man in charge of the G.U. Clinic of this hospital for the past five months. During this time he has been under my daily observation and I can frankly say that I have never seen a more conscientious hard-working young man in my life.

Private Noorlander is a well-educated, having had two years in college. He is courteous, has no bad habits, and his devotion to duty is certainly far above average, and I know that in whatever position this boy is put, he will assume the responsibility of his job and will work hard to attain excellency in any work or subject that he may be assigned.

I can frankly say that never, either in civil or military life, have I had the privilege of recommending a man whom I knew to be as loyal, hard-working and trustworthy as this man.

Hobart D. Belknap, Lt. Col.

Medical Corps, U.S. Army Chief, G. U. Service

He also gave me his Eagle wings as a gesture of good faith.

Infantry School

Infantry School in Ft. Benning, Georgia (April 27, 1942 to July 25, 1942), was not easy. In all my life I had only fired a 22 rifle. Before it was over I learned infantry tactics and how to fire all the basic infantry weapons. Discipline was harsh, but I was mentally and physically prepared. It was apparent that I was the youngest in my class of 39.

The Infantry School graduated about three classes a week, so it was also apparent that the Army was just beginning to gear up for the war that had already started. They must have been desperate, or otherwise why would they have taken a chance with someone like me, who hardly shaved and had never stood in formation before being sent to the school.

What the Infantry School did not teach me, was what a second lieutenant did when surrounded by the enemy without any communication, food, or medical help. It never taught me how to cope with swarms of black flies that hatched from maggots, which became so numerous in the rotting flesh of a human body that they literally moved the carcass.

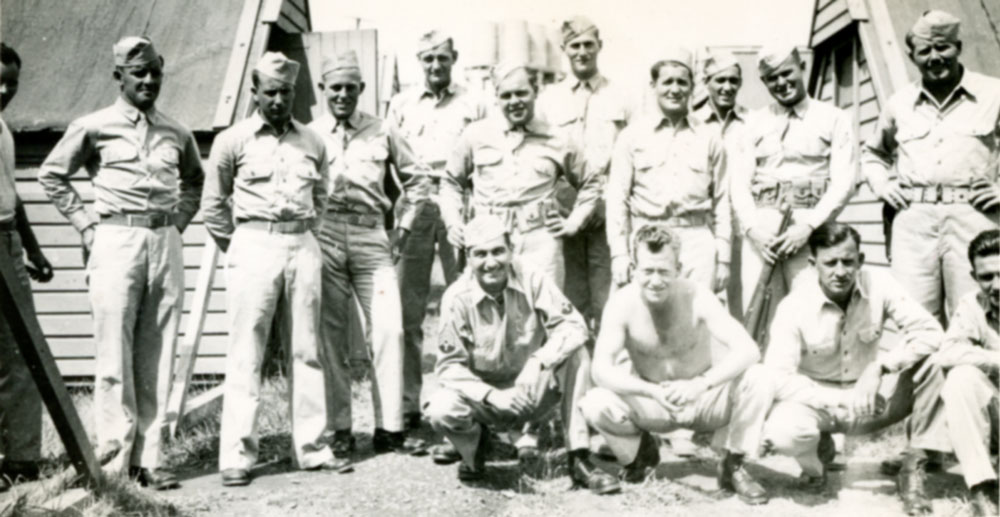

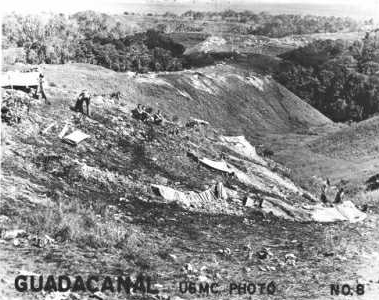

Hawaii

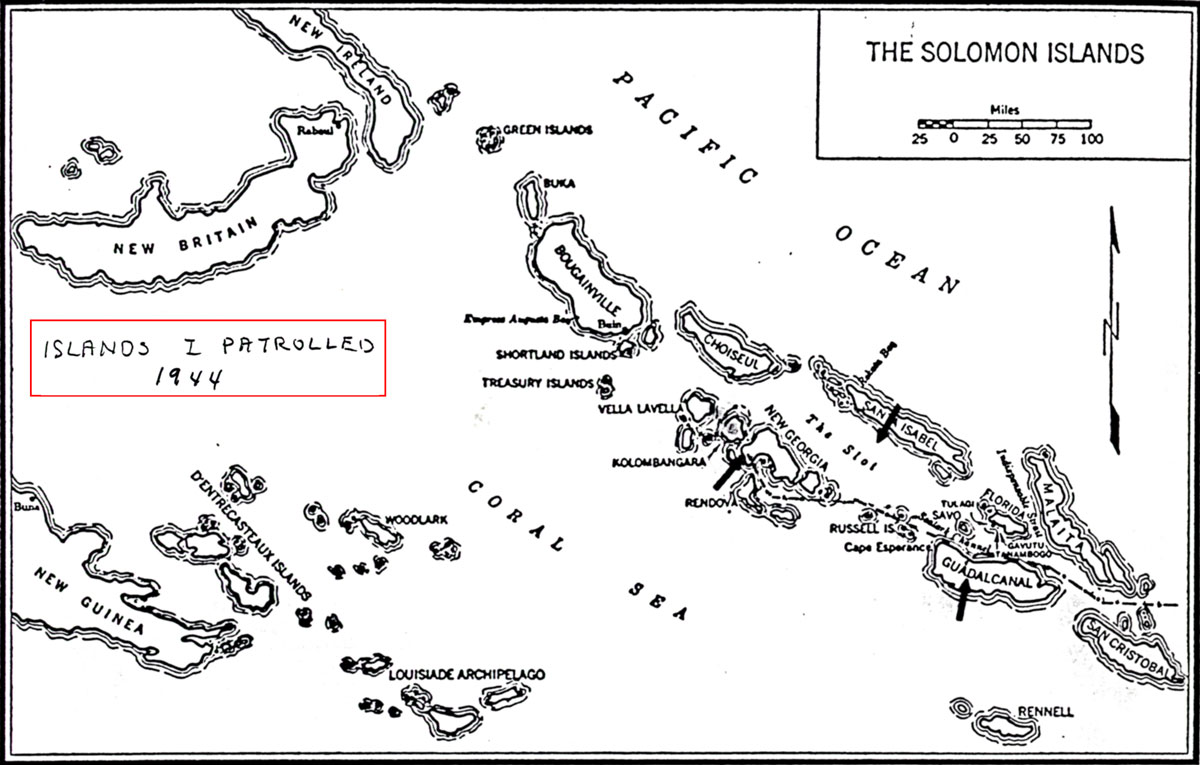

My first orders were to join the Hawaiian Pack Train that was destined for Burma, but the situation in the Aleutians and Soloman Islands became so desperate that most of our class headed for the Pacific not really knowing where we were going.

I ended up with the Washington National Guard, which had been assigned to the 25th Division in Hawaii. It did not take me long to find out that the Japanese soldier would not be my only enemy.

Many years after the war, I learned from a friend of mine, who shared many Army experiences with me, and who preceded me as a graduate of the Infantry School by about three weeks, why I was ordered to take almost every important and dangerous patrol in our outfit, and why I was never promoted above first lieutenant: “Lt. Noorlander is a good combat officer,” they would say, “but he is hard to handle.”

Later I was offered a promotion to Captain, but was told it would put me “behind a desk.” I said, “No thanks.” I was most effective in front of a patrol, and I knew it.

Leadership Problems

It was apparent that I was not really destined to make the military a career. Like thousands of other soldiers, I joined the Army because our nation was threatened. I found out that the biggest threat to some of our citizens came from certain military leaders.

My first assigned company commander, a National Guard Captain, was no exception. He can best be described as a ‘banty rooster,’ who appeared to have received his military training from a mail-order house. I learned later that this was actually how he got his commission. The captain frustrated almost every effort I made to train the men under my command, a platoon of about 40, most of whom were also National Guardsmen many years older than I was.

I was one of the first officers to be assigned to the National Guard from the United States Army pool. I was an outsider infringing upon a close-knit hometown club of men, which up to this time had everything their own way.

It was apparent to me that the company commander liked his position of authority. It was also clear that he had little military knowledge or experience to go with it. Having been formally trained, I got the impression very quickly that I was not welcome, and that I was, for whatever reason, a threat to his position.

Training Exercise

A typical reaction to my training effort came one morning as the company stood at attention waiting to be dismissed for the days training. I had prepared my non-commissioned officers for a special stream crossing exercise that I learned at Fort Benning in Infantry School. The whole platoon was to cross a river with weapons mounted on top of small rafts made out of shelter halves (the halves of our pup tents), which all soldiers carried in their back pack. We were to cross under cover of smoke. The preparation for this took a lot of time and effort, which the company commander knew about. I didn’t count on the commander being concerned that one of his junior officers knew more about military tactics than he did. Apparently he felt threatened.

As we stood at attention that morning, I knew that he was going to screw up the day. He ordered my platoon to fall out and report to the supply tent for an issue of shoes. This could have been done after training, but this captain was still smarting from a confrontation he had with me just a week before.

Earlier Confrontation

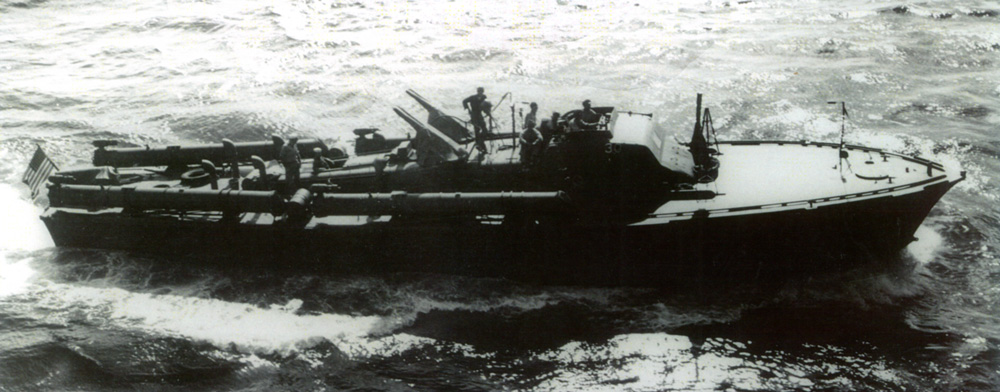

My platoon was assigned to protect a stretch of beach front, about half a mile, on the north side of Oahu in case of a Japanese landing. Barbed wire had already been used to make ten-foot-high barricades just off the beach. The only artillery I had at my disposal was two small one-pounder canons that fired a projectile about the size of a small lemon. I also had at my disposal two battery operated search lights just inside the barbed wire, and two cement pillboxes in front of the wire that had probably been there since World War I.

I decided to test the equipment and the preparation of my men in case the Japanese decided to attack Oahu with their naval forces. I knew that asking for permission to do what I had in mind would be a waste of time.

The opportunity came, however, when a small fishing boat was sighted by one of my men just off the beach a few hundred yards from the shore. It could just be seen by the reflection of the moon. With a little imagination, it became one of those small Japanese submarines the Navy found beached during the attack on Pearl Harbor.

I ordered a red alert and my men scrambled out of their tents and mounted their machine guns in the pillboxes. I ordered the search lights on, and told the men to half load their machine guns. What happened next was hard to believe. It was apparent that no one had turned on the lights or positioned machine guns in the slits of the pillboxes since World War I.

The lights reflected off the barbed wire making it impossible to see beyond the wire. The machine guns, positioned in the cement slits of the pillboxes, could not be elevated because the cement was warped. If we had fired the guns, the bullets could not have hit anything beyond 10 feet.

As expected, the Company Commander split a gut when the Island Commander phoned to find what all the fuss was about on the beach. Awakened from his sleep, he didn’t know how to answer him.

I had to take the brunt of a verbal lashing for not asking permission to turn on the lights. I felt it was easier to ask forgiveness than to ask permission, but ‘old banty’ did not share my feelings and was out for revenge. He was not about to let me proceed with my training that morning.

Placed Under Arrest

When the Captain ordered my platoon to get their shoes without telling me about his plan, I challenged his authority by ordering my men to stand fast. What ticked me off the most followed. He tried to embarrass me in front of my men by making light of my effort to prepare them for combat. I knew that we had only a few weeks before leaving the Hawaiian Islands to fight the Japanese. From what we learned on the radio, the Marines were having a bad time in the Solomons, and rumors were flying that we might be headed there.

I explained to the Captain that we were just leaving for our training exercise, and asked permission to get our shoes later. He responded by ordering my platoon to get their shoes. I responded like the stubborn Dutchman that I am, by ordering my men to stand fast (again).

“Lt. Noorlander,” he bellowed, stretching all of his five-foot-eight stature as tall as he could: “Consider yourself under arrest and confine yourself to quarters!”

“Yes, sir!” I responded with the same icy tone. I turned my platoon over to my sergeant who seemed to enjoy the confrontation.

Intervention

The next day the Battalion Commander entered my tent and asked me what was going on. He wasn’t such a bad guy as commanders go, and I had an idea that he knew I was not the only problem in Company C, 161st Infantry.

“Well,” I started. “I joined this man’s army. I was not drafted and I don’t care if I fight the Japanese as a private or as a lieutenant, but it is my opinion that we cannot win this war with meat heads like the Captain.” Then I explained what happened, including our problems on the beach with our defensive positions, and the opposition I received training my men for combat.

My short time in the Army had taught me enough about army politics to know that a court martial would only expose a situation no commander wanted—a shavetail like me placed under arrest because he happened to think that his men’s lives, which depended upon their military training, took a back seat to the whims of a “mail-order” Company Commander.

I also knew that this Major could not expose his hometown Company Commander’s deficiencies by agreeing with me. Instead, he asked if I would like to join another company under his command. “You bet!” I replied without hesitation and with some relief.

The new Company Commander and I became good friends. His name was Capt. Patton, and he had his head screwed on right. My life in the military became bearable again.

Respect Earned

There wasn’t much time for more military training. Preparations had started for packing up and preparing to load ships for embarking. My new platoon and I got along really well. They heard about my confrontation with ‘old banty’ and accepted me as one of them. At the same time they respected my rank, and the discipline that had to be maintained. They knew and I knew that we were no longer playing at war, and that we were going to be tested. As far as they were concerned, I had passed my first test—I had guts enough to stand up to authority when it mattered. In this case, I stood up for the welfare of the men under my command, whose training I took seriously.

Building Moral?

A taste of what I could expect from the Army when it came to its idea of building moral took place a few days before leaving Hawaii. The commanders decided to put on their own USO show, and give the men a double ration of beer. Some soldiers did not drink or like beer, which meant that others had more than a double ration.

As the show’s Hawaiian dancers came on, the men were in a drunken stupor. They threw empty beer cans at the dancer’s feet. They heard there was going to be a striptease artist and didn’t want to wait for the dancers to finish. When the striptease artist came on stage, bedlam broke out. Empty beer cans were replaced with full ones. Some of the tossed cans hit the heads of the men up front. Cuts and broken heads put several of the GIs in the hospital, and they never made ship.

I thought that the Hawaiian dancers were pretty good. I didn’t know very much about the ladies, particularly naked ones, so I couldn’t understand what all the hooting and hollering was about. I knew this wasn’t the way to prepare men for war.

.jpg)

;

;