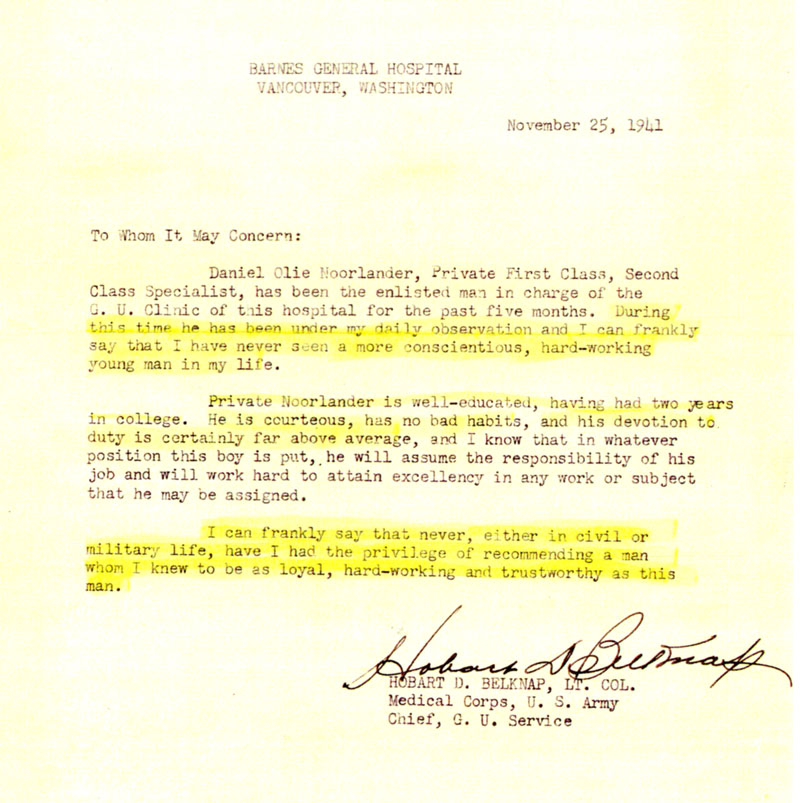

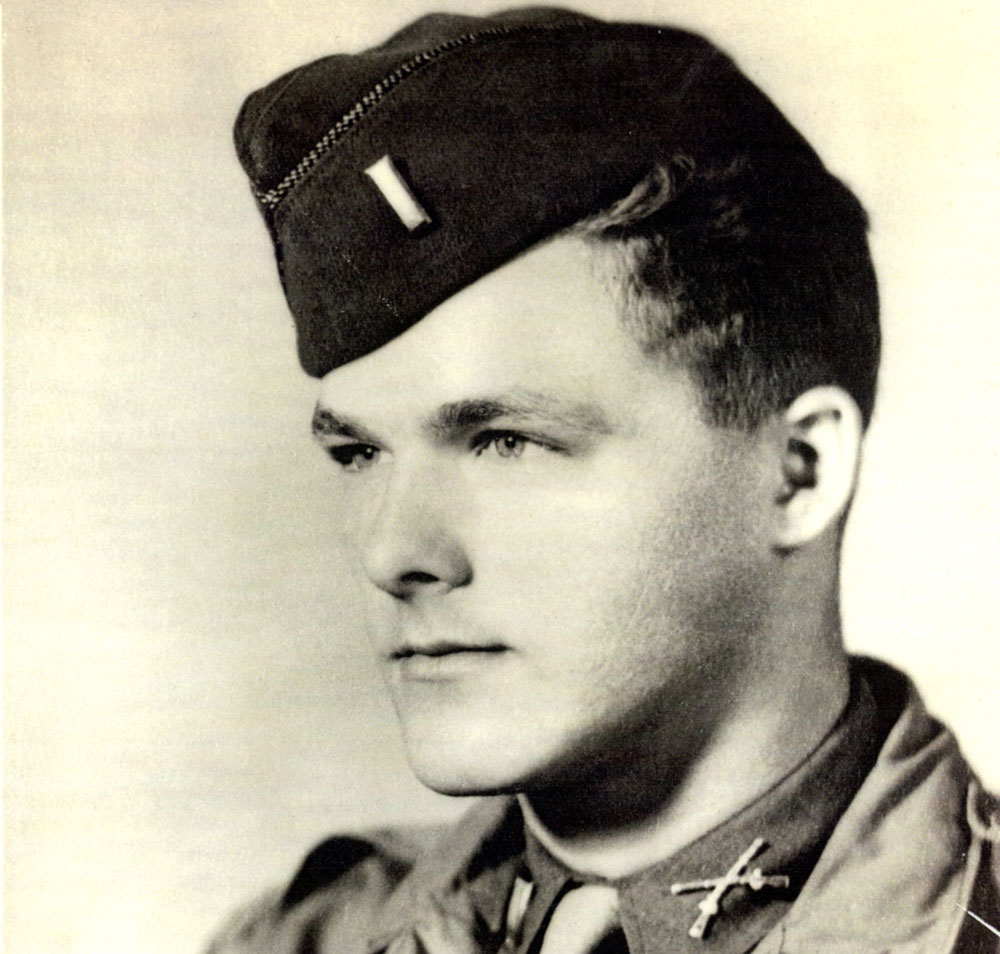

Lieutenant Dan Noorlander

March 12, 1921 — October 3, 1990

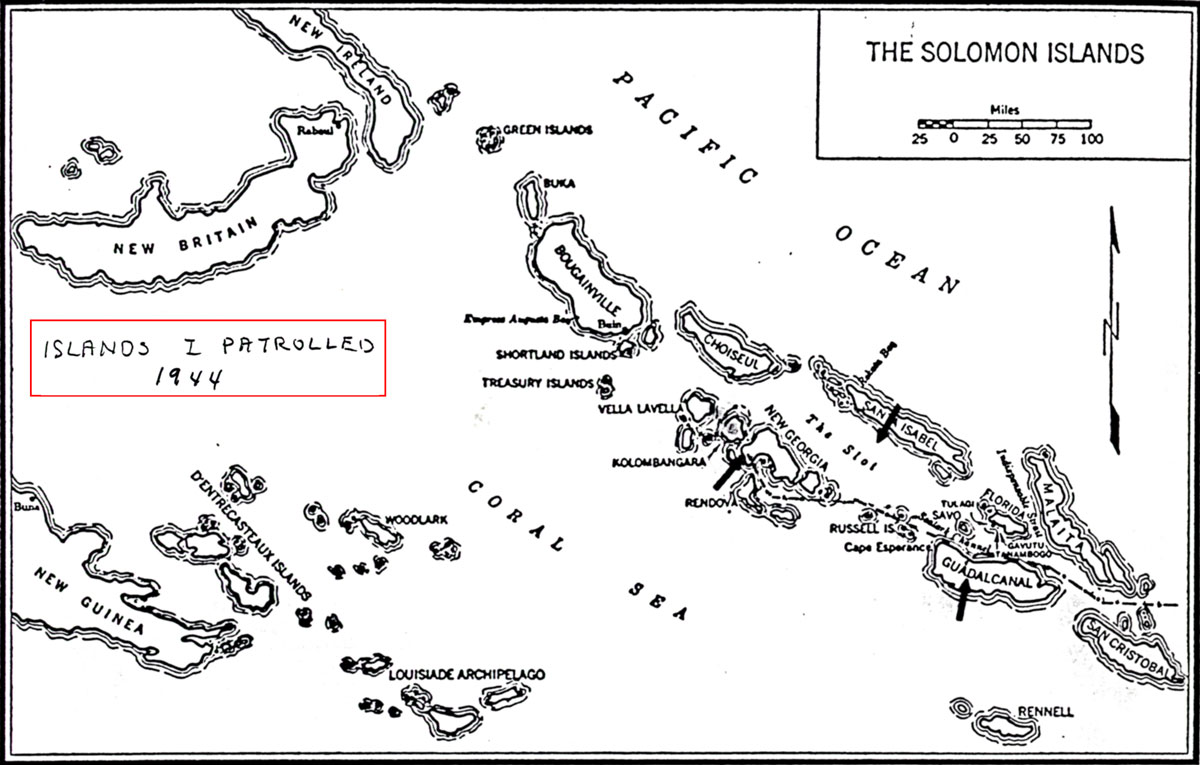

Guadalcanal

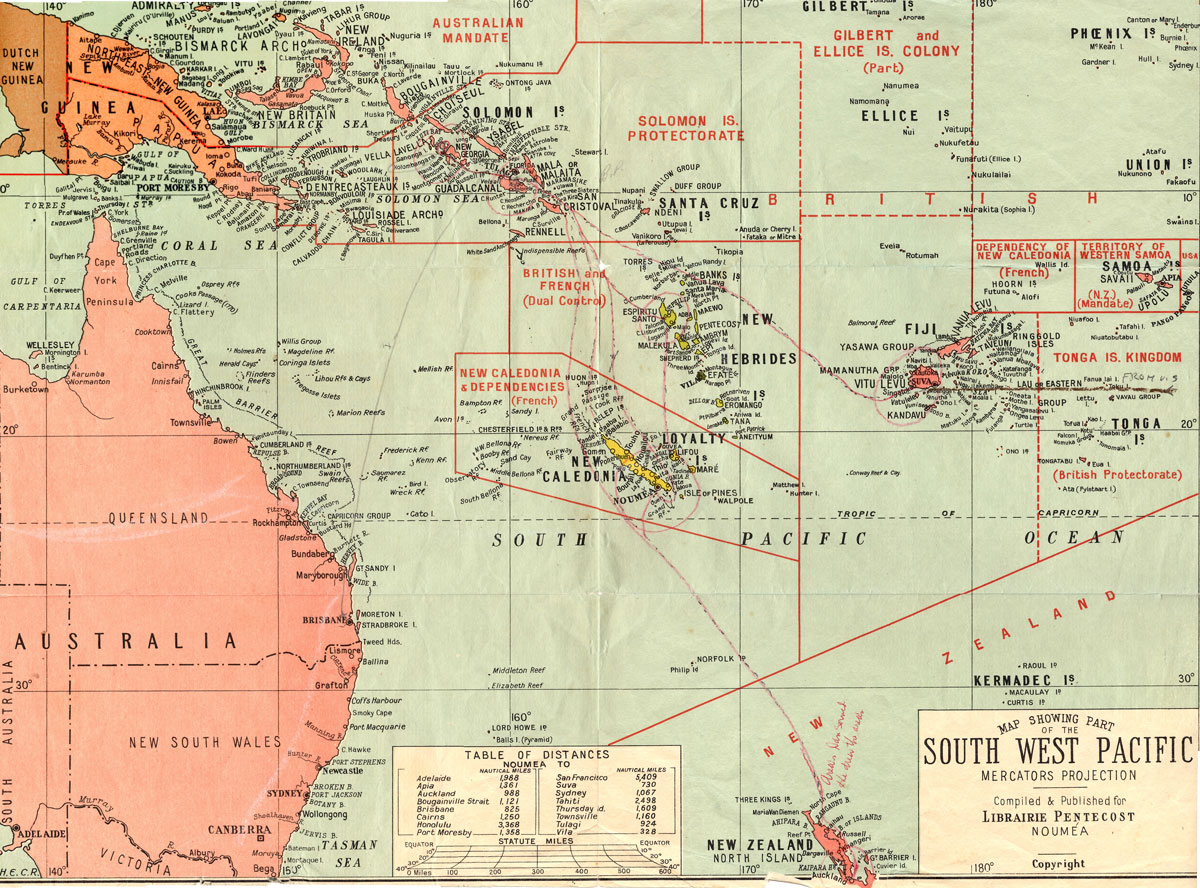

The Battle of Guadalcanal was the first major offensive against the Japanese Empire in WW II. It was conducted by Allied forces (mostly U.S. Marines and Army Infantry) between August 7, 1942 and February 9, 1943.

Together with the Battle of Midway, it was a turning point in the war against Japan. The offensive operations that followed on the other Pacific Islands resulted in Japan’s surrender and the end of WW II.

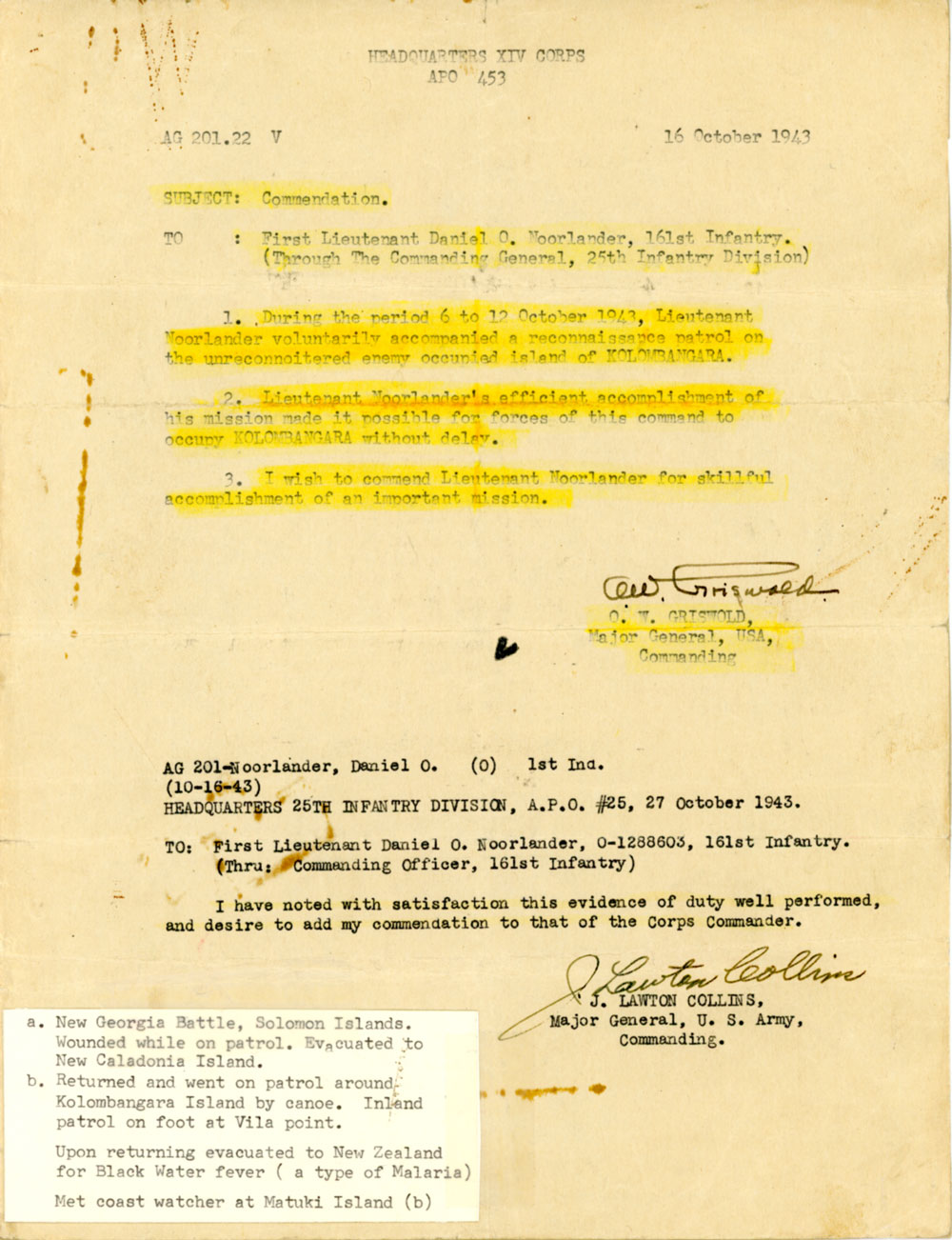

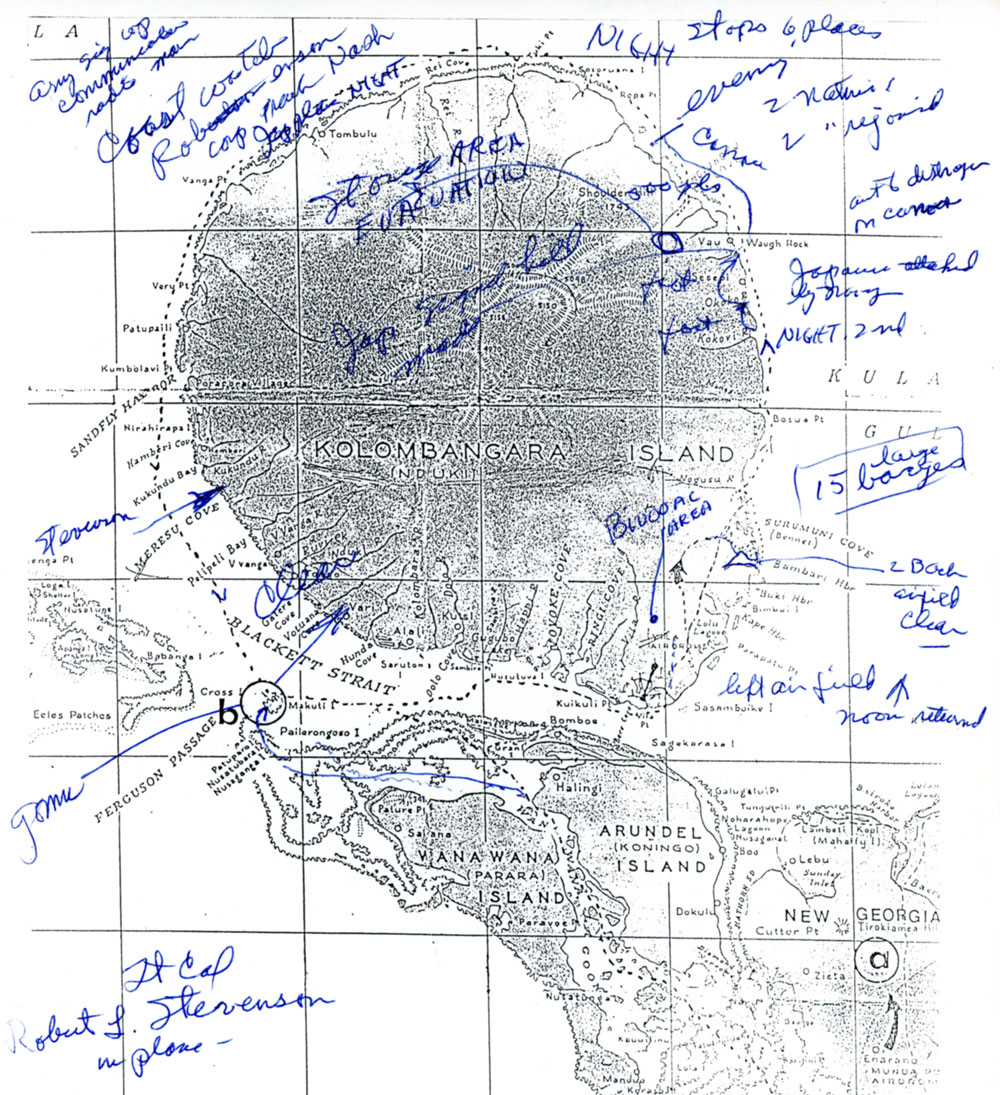

Lt. Noorlander’s Account

Mopping Up After the Marine’s Initial Invasion of the Island

Guadalcanal Campaign

The 161st Regiment was an infantry unit of the Washington Nation Guard, of which Lt. Noorlander was a part. During WW II it was assigned to the Army 25th Infantry Division based in Hawaii.

The 25th was sent to Guadalcanal to reinforce the Marine forces, who began the attack August 7, 1942. The Army’s assignment was to eliminate all remaining Japanese pockets of resistance.

After intensive training in Hawaii, the 25th began moving to Guadalcanal November 25, 1942, arriving by January 3, 1943. The Army offensive in which Lt. Noorlander played such an important role, lasted from January 10, 1943 to January 21, 1943, and effectively ended the battle for Guadalcanal. Nearly 7,000 Americans died in the Guadalcanal effort, which lasted six months.

Compare the summary descriptions of the Army’s mission in the next column with Lt. Noorlander’s account, who lived through it. The horrific realities of war are sometimes lost in historical perspective.

The Army’s Mission

Two summary descriptions of the military operation Lt. Noorlander took part in:

“The 161st Regimental Combat Team arrived at Guadalcanal in early January 1943 and took up defensive positions around [Henderson] Airfield. The 161st entered the attack phase on January 6, 1943, with an assault on Japanese forces in a jungle redoubt called the Matanikau River Pocket. Here Japanese troops employed skilled camouflage and well-defended positions to take a heavy toll on the attackers. The assault lasted from January 10 to January 21, when the resistance was overcome.” (History compiled by Duane Colt Denfeld, Ph.D.)

“While manning defensive positions around the airstrip, named Henderson Airfield, the 161st was also handed the assignment of eliminating a concentration of Japanese troops in what became known as the Matanikau River Pocket. The Pocket, estimated to hold 500 enemy troops, was a dense jungle redoubt positioned between a steep hillside and a high cliff over the Matanikau River. The heavy undergrowth masked the well-camouflaged Japanese positions, both on the ground and high in the trees, and made dislodging them a slow, grim task.” (History compiled by the 25th Infantry Division Association).

Lt. Noorlander’s Account

The mission to eliminate Japanese pockets of resistance on Guadalcanal

The day finally approached when we were given orders to start packing and board one of the liberty ships tied up in the docks at Pearl Harbor. I only had about a month to get acquainted with my new platoon and prepare them for combat. After we left the harbor time was spent trying to sleep in our four-tier canvas hammocks below deck, clean weapons, eat, and generally kill time. Trying to bathe in salt water was a new experience and the special soap for this purpose did not do much good.

After we were out to sea a few weeks, our direction turned southward and rumors started to fly. We had heard that the marines were having a bad time on the Solomon Islands, but our destination was pretty well kept a secret until the very last few days before we climbed down the rope ladders into waiting landing craft. We were told by a Marine officer that we would relieve them on Guadalcanal.

Relieving the Marines

When the marines landed a few months before, they met little resistance on Guadalcanal. But as soon as the Japanese overcame their surprise and confusion, resulting from the enormous firepower of the Navy and Air Force that preceded the landing, they regrouped from the jungles and attacked the marines in force. Since the marines were dug in, the Japanese took heavy loses.

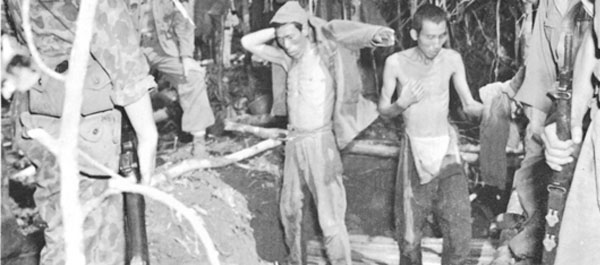

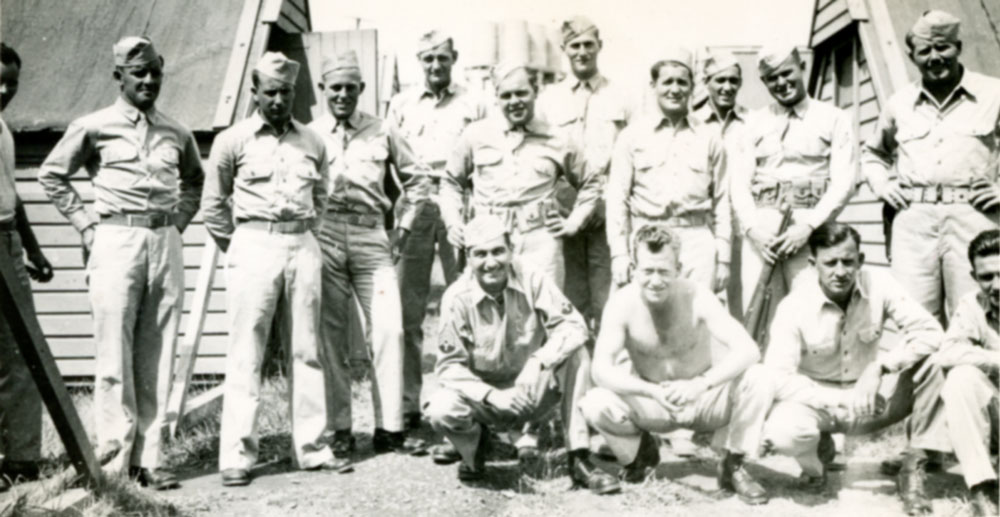

Marines rest during the Guadalcanal campaign.

When the Army infantry division relieved some of the marine positions and expanded the perimeter around the remade airfield at Lunga point, they found as the marines did, that jungle warfare is quite different from what the army manual taught about infantry tactics.

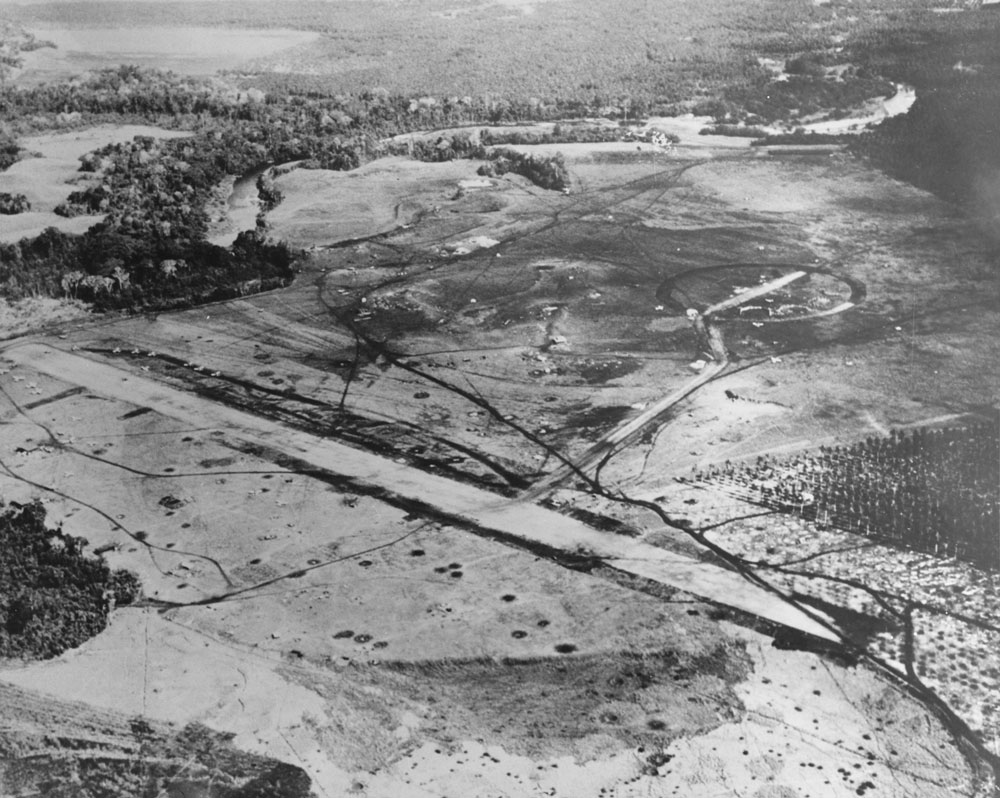

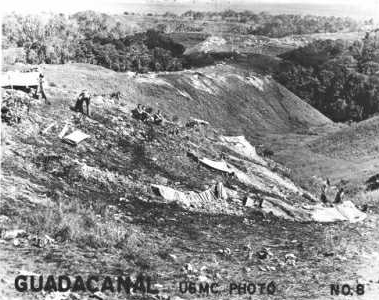

Henderson Airfield at Lunga Point on Guadalcanal — The airfield was originally built by the Japanese to patrol the southern Solomons, the shipping lanes to Australia, and the eastern flank of New Guinea.

Military Tactics

There was only one way to dislodge the enemy from dug in camouflaged positions along a jungle trail, on top of a jungle mountain, or in a deep vine covered ravine. Individual foot soldiers on patrol would crawl, walk, or crouch into the thickly forested jungle until the enemy fired at them. Then it was a matter of trying to figure out how many of them were there and where their positions were. This was not an easy task.

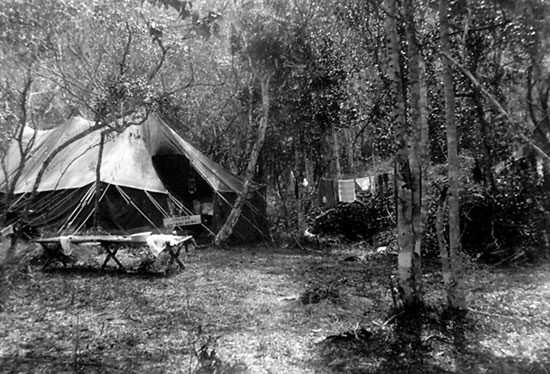

Unknown soldier in the jungle of Guadalcanal.

When the Japanese opened fire on our patrols, the bullets would strike a leaf or branch over or around our heads and literally explode with a sharp crack, making it impossible to tell where the enemy was except from a general direction.

The patrol would then attempt to go around the flank of the enemy to determine if the fire came from just a sniper or from dug in positions. Each decision that was made was accompanied by casualties and dead soldiers. It was always a trade off. Dead bodies for information concerning the enemy.

After so many casualties the brass would then determine if the heavy stuff should be used such as artillery or mortar fire. Mortars had the advantage of lobbing shells in a high arch so they would land relatively close to our positions. Artillery had the disadvantage of hitting tree tops that often caused heavy casualties among our own troops and had limited use in close up jungle fighting.

Mopping Up

This was the type of warfare the 161st infantry was assigned to carry out. It was out mission to engage the enemy in what was called a “mopping up” operation. The Japanese were known for not surrendering. The only thing going for us was that the Navy and Air Force had blockaded all their supplies including their food. The Japanese on Guadalcanal were in a half starved condition when we encountered them, but it did not take much energy to pull a trigger on a light machine gun, and they still had ample ammunition.

Soldiers stand guard over some of the few captured Japanese defenders on Guadalcanal.

Although we knew the Japanese had gas grenades, they did not use them on us. We also had gas which they were well aware of. Consequently, when we landed on the beach with our gas masks, we dumped them in a large pile as we headed for the perimeter of defense to take our positions.

The first night we slept in our shelter halves to keep the rain from getting us wet. When in fox holes or slit trenches, usually a helmet sufficed to keep the rain out of our faces. We only had one casualty that night. It came from a self inflicted shot from a 45 pistol. One of the GIs could not face the idea of fighting in this remote jungle. During the night we could hear his groans, but no one dared move to help him.

The next morning, my platoon relieved a marine platoon that was already dug in. In front of us was some barbed wire and trip wires to slow down any potential enemy attack. We patrolled that day for about a 1000 yards in front of our positions but met no enemy. That evening I placed some booby traps in front of our positions to alert us in case the Japanese came too close. There was no activity during the night, although we could hear the fighting to our right where the 35th and 27th infantry were engaged in a mopping up operation in the southwest part of our perimeter that lay just this side of the Matanikau River.

First Combat Experience

My platoon’s first combat experience came when I was ordered to wipe out a few snipers on the other side of the river to protect our regiments flank as they prepared to attack up the coast to the end of the island.

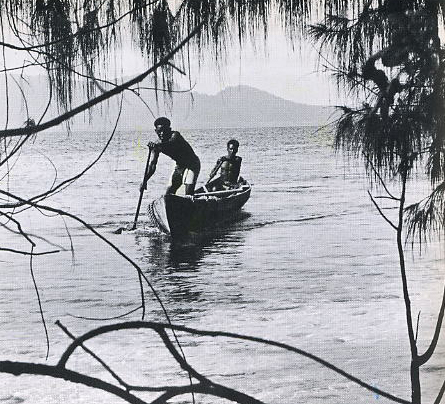

Mouth of the Matanikau River.

I had confidence that we could handle the job. During the preceding few days, my platoon learned to work well together in the jungle—particularly in how we communicated with another using hand signals.

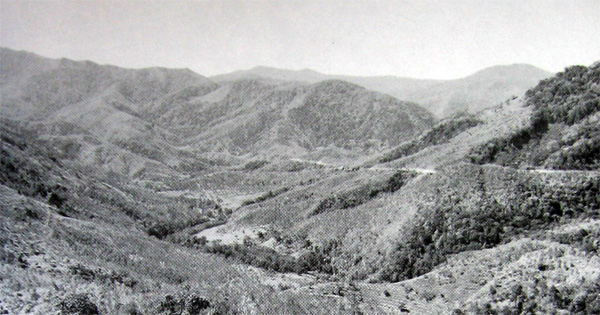

The 25th Division’s first offensive zone was west of the Matanikau River (January 1943). Fighting was concentrated in the area of Hills 54, 55, and 56 (above).

We left our defense area in a grassy ridge just overlooking the dense green forests that formed a plateau rising about two hundred feet above the Matanikau River. The river marked the boundaries of our most advanced positions.

My platoon led out. Traditionally, I had two scouts out in front of me—private Marmalejo slightly to the left and private Eddie Lorenz to the right. Private first class Frank Smiderly followed me by a few yards followed by Sgt. Keifer. The rest of the platoon followed slightly staggered on both sides of the winding trail that lay between the river and the hills above us. We were cautious knowing that a crack of Japanese firepower was the only thing that could stop us. It was only a question of when and where. One of our main problems was that we did not have much room to maneuver on this narrow plateau.

We did not have to wait long. Marmalejo was dropped by a single shot from a sniper. Lorenz on my right was also shot. Almost immediately, a machine gun burst turned up the soil in front of me, heading directly for me. I jumped right to the side of a tree. I could not see the enemy. The cracking of bullets appeared to explode as they hit the leaves and branches all around us. Chips of bark came from the tree right above my head. Some rounds made a groove in the bark. I lined my M1 rifle to correspond to the direction made by the groove and pulled the trigger eight times in rapid succession. The firing stopped, at least from where the sniper was positioned in a tree.

I crawled over to Lorenz on my right who was still alive. He had a bad wound in his chest. I placed my hand under him to see if the bullet had penetrated his body. It appeared to be only a deep flesh wound that tore a hole in his chest. After I packed the wound with mud, he attempted to crawl to safety. It was impractical to call a medic. My whole platoon was pretty well pinned down. I could not risk having the medic expose his life this far up the trail, so I did what I could.

I dug the mud out of his wound with my fingers, then cut up some sulfa tablets with my bayonet and pushed them deep into the wound. After I applied a pressure bandage, Smiderly with the help of his buddy, placed Lorenz on a shelter halve and pulled him to safety. Eddie Lorenz was an Indian from Montana and I remember in Hawaii a discussion we had concerning his anxieties about the war. I told him not to worry and to stick close to me. I’d see to it that he got home. I hoped that I had not let him down.

A wounded 25th Division Army soldier is assisted off the line in the hills near Matanikau River, January 15, 1943.

I observed our company medic cutting down a tree sapling to form a splint for another one of my men who was shot in the leg. I ordered him to get down. I did not want any more casualties. I regrouped what was left of the platoon a little to the rear, and ordered them to dig in. Digging slit trenches was not easy among the network of large tree roots that lay over the surface of the clay-like soil. After preparing our defenses, we settled down for the night. It was getting dark.

Japanese Fortifications

The next morning we prepared to attack the Japanese positions, still thinking there were only a few snipers. As we went forward in crouched positions with new scouts from another squad, I tried to maneuver a little to the right. I saw my left scout almost run into a Japanese soldier, who got up from what appeared to be a well dug in trench. The Japanese soldier was actually stretching his arms, which indicated he was unaware of our position so close to his own. It was also apparent that we were facing heavily fortified positions, and that there was more than just a few snipers.

Japanese soldier tosses grenade on Guadalcanal.

I did not want to yell out to my scout that he was just about to expose himself in a well fortified area. His job was to find the enemy, but in this undergrowth he could not see what I observed from the side. I instinctively pulled a pin out of one of my grenades and threw it well over his head, as close to the Japanese position as I could. This alerted my platoon and we dove for cover. Again all hell broke loose, but this time I had a better respect for what was in front of us.

There was really not much we could do. If we went forward, it would be certain suicide. I was not about to order my platoon to fix bayonets and charge well dug in positions. The infantry soldier’s job was to engage the enemy and use basic infantry weapons to kill him. Rifles were not the only weapons I was trained to use.

I sent Captain Patton a message about what we were up against. He came down with part of the company to reinforce us. By then I had only 14 men left.

New Orders

When Captain Patton arrived, I learned that the third platoon had been ordered to charge down the hill, supposedly to attack the Japanese flank. It was literally wiped out with machine gun bursts. I didn’t believe that he was capable of making such a stupid decision all by himself, and thought that he must have received his orders from one of his home town buddies who thought that we were fighting World War I.

Captain Patton informed me that we had to attack again. Apparently, we were holding up the army’s advance. Lt. Ferriter (35th Infantry), was on patrol activity below us on the Matanikau River. He found that the Japanese, except for a few stragglers, were for all practical purposes not a threat in front of the two regimental lines. Lt. Ferriter, however, did not know about the stronghold across the deep ravine where we were pinned down.

“You must be kidding,” I told Captain Patton. “Where is the mortar fire we ordered?”

“It isn’t available,” he responded. “Why don’t you take your platoon and go as far as you can, and we’ll try to maneuver around them with a fresh platoon.”

Captain Patton was somewhat older than I and a family man, and I didn’t think he could make it. “Look, I think I have a better plan. Just below the plateau there appears to be enough footing to sneak around the enemy’s position. If we are careful, and quiet, we might be able to attack from the rear where the Japanese defenses are probably less organized.”

Captain Patton agreed with the plan, and I led out. There was no need for scouts because we knew where the enemy was. We didn’t, however, know their strength. Our strength was what was left of my platoon, a fresh platoon from the company, and a machine gun section from another platoon. Light mortars from the weapons platoon were useless in that thick jungle where we could barely see the sky.

About two hours later and about a thousand yards alongside that Matanikau cliff, I decided to turn to the right and upward in preparation to attack the Japanese. As my platoon crawled up the embankment to the plateau to await my plans, an alert Japanese soldier apparently heard someone from my platoon. He sprayed the ridge in front of me with machine gun fire, but not before I counted at least a dozen deeply dug in bunkers lying in a shallow ravine to our front.

The spine of ridges extending from Henderson Airfield southward into the jungle. In the early days of the war, most of the heavy fighting on Guadalcanal took place along these strategically important ridges.

As I hit the dirt, I lost my footing alongside the cliff and fell backwards. To stop my slide, I embedded the pick mattock from my belt into the side of the cliff, which held me. Looking down at the river I saw a tall tree just below me. I thought I might have a chance if I jumped onto the tree top and climbed down the branches.

At that moment, my sergeant spotted me and leaned down with a branch that he broke off from a nearby tree. He pulled me up and I could see the whole company leaning against the side of the cliff with no where to go. The Japanese were in front of us. The river was behind us—two hundred feet down. This was no place for Johnny doughboy. What a situation to be in. I wondered to myself, “What did I get this company into?”

It took about two minutes of frustrated thinking before the answer came to me. I had the men pass the word down the line to remove all their rifle slings and join them together. Captain Patton was toward the middle and we couldn’t communicate, but I was sure that he would agree. Besides, we really didn’t have a choice. We decided to go down the side of the cliff hand over hand using the rifle slings for a rope.

When all of us had reached the bottom safely, we headed down stream to where we could go back up the trail where we had started. It was getting late, it was our third day out, and I was getting a little frustrated. The river water came up to our necks in places, so we carried our weapons and ammunition over our heads so they would not malfunction. I was told later that this experience was reported on the radio back home.

Request for Support

I asked Captain Patton again to ask for some help in the way of a little mortar fire from the hills above us. “And I mean some heavy stuff,” I emphasized!

He got on the wire phone laid down for us, but the expression on his face told me the response from our battalion leaders was negative.

I had just about had it. “Give me that phone,” I demanded. Then I slowly but firmly told whoever was on the other end of the line, that unless we got some mortar fire in front of us I was pulling the troops out. I didn’t want to take over Captain Patton’s job as company commander, but he was hardly in a position to give orders to his higher ups. He was a real nice guy, but not much of a combat soldier. Frankly, I didn’t care who I was talking to: “Just in case there is a misunderstanding, I want you to know that we are pulling out unless we get some mortar fire.” Then I said very slowly so he could understand: “Look, I only have 11 men left. I still have one dead man out there someplace and this is no place to play games. Do we get mortar fire or not?”

“Just one minute, Lt. Noorlander,” came the response. It was apparent that someone else took the phone on the other end of the line. It took just about two minutes, and I heard a reassuring voice tell me to pull out, and that mortar fire would be coming in after we cleared the area.

We tried to mark our forward positions by firing some smoke grenades, but it was Private Peralta from the third platoon, who gave us the exact positions of the Japanese on the Matanikau River plateau. He had been trapped for two days and two nights among the Japanese before finally making it back to our lines.

Fallen Soldier

Before we pulled out, I asked for a volunteer to help me find Marmalejo. I had no right to order anyone to go with me nor did I expect anyone to volunteer, but Sgt. Lollick stayed behind to help as the remnants of Charley Company withdrew to the hill positions overlooking the Matanikau River.

After our company left, Sgt. Lollick and I covered each other. We spread about 15 yards apart with each of us moving forward toward the area where private Marmalejo was last seen. We crawled over the ground with our bellies, but apparently one of us moved a branch. A burst of machine gun fire swept over us. We crawled back to where we felt safe to stand up and literally ran to catch up with the rest of the company. I knew there was not much we could do for Marmalejo.

When we finally arrived at the original company area in the hill overlooking the Matanikau River Pocket we were exhausted. Sgt. Lollick turned into the medics for some ailments he had, but didn’t tell me about until this phase of our mission was over. I never saw him again. Lollick was a brave and loyal soldier.

Mortar Support

All that afternoon and during the night, orders were given for the Navy’s construction battalion to bulldoze a road below a hill just in front of the Matanikau River Pocket where 4000 81 millimeter shells were stock piled.

Starting at daybreak, the mortar company commenced firing all 4000 shells into a jungle pocket, which measured perhaps 200 yards by 1000 yards. Most of them fell in the area that we had marked with grenade smoke.

As each salvo of a complete battery of mortars arched through the sky just in front of us before reaching their targets, I could hear the men yell in elation with insults to the Japanese General Tojo, which in essence stated that Tojo eats the final metabolized residue of the food process.

After the smoke had cleared, I was given another assignment. It was now clear to me why I was picked for all the difficult assignments. I was not a regimental reconnaissance officer, just an infantry platoon leader. Nevertheless, I was ordered to mop up the remnants. As the commanders explained it, I knew the area well. It was true that some of the companies were preparing for the final push up the coast, but there were after all some 30 infantry platoon leaders in the regiment. Our company received most of the casualties, and it was my platoon that did most of the dirty work fighting the last of the organized Japanese resistance on the Island of Guadalcanal. The fighting here was almost over.

Making a Friend

I did not see how the Japanese could have survived such a massive mortar barrage. When I entered the bombed out area with my platoon, which had been reinforced with some new men, I approached the former Japanese stronghold and surprised a somewhat stunned Japanese soldier. He had two raw bones exposed from one of his arms. Only the maggots had kept it clean. He looked like a skeleton with just enough muscle to move his frame. When I offered him some water out of my canteen and a piece of chocolate “D” ration, he bowed down to me with clasped hands and offered me his watch. It was apparent that he had not eaten anything but the tender parts of green leaves for weeks. We suspected that other Japanese soldiers ate from the human liver remnants we found in a canteen cup.

I refused this Japanese soldier’s watch, but had made a friend that proved to be very valuable. My sergeant was just about to enter a dugout missed by the mortars, when the Japanese soldier waved him away, warning us that it was too dangerous. I ordered a grenade thrown in the bunker. It went off, but apparently did no harm to another Japanese soldier who came flying out of the bunker, running down toward the river. I motioned for one of the squads to stop him. Two rifle bullets put him out of his frightened state of mind.

Sgt. Kiefer reminded me of this story when he came to visit me after the war. He said: “That day I was taught a great lesson about compassion and love, even to your enemies.”

Finding Marmalejo’s Body

As we passed through the bombed out area, there were bodies blown every where. Some laid on the lower branches of trees. The next day I returned to the general area by myself. I had to take one more look to find Marmalejo’s body. As I looked into one deep bunker, there were several bodies lying on top of one another, already in a state of putrefaction. The stench almost caused me to vomit. I walked further on to where we first engaged the Japanese. There was Marmalejo’s body lying just in front of a dug in position. I removed his dog-tag, which slipped through his decomposed neck bones and left them on his body for identification. I found out later that this was a Japanese hospital area protected by what was left of the only organized resistance on the Island of Guadalcanal.

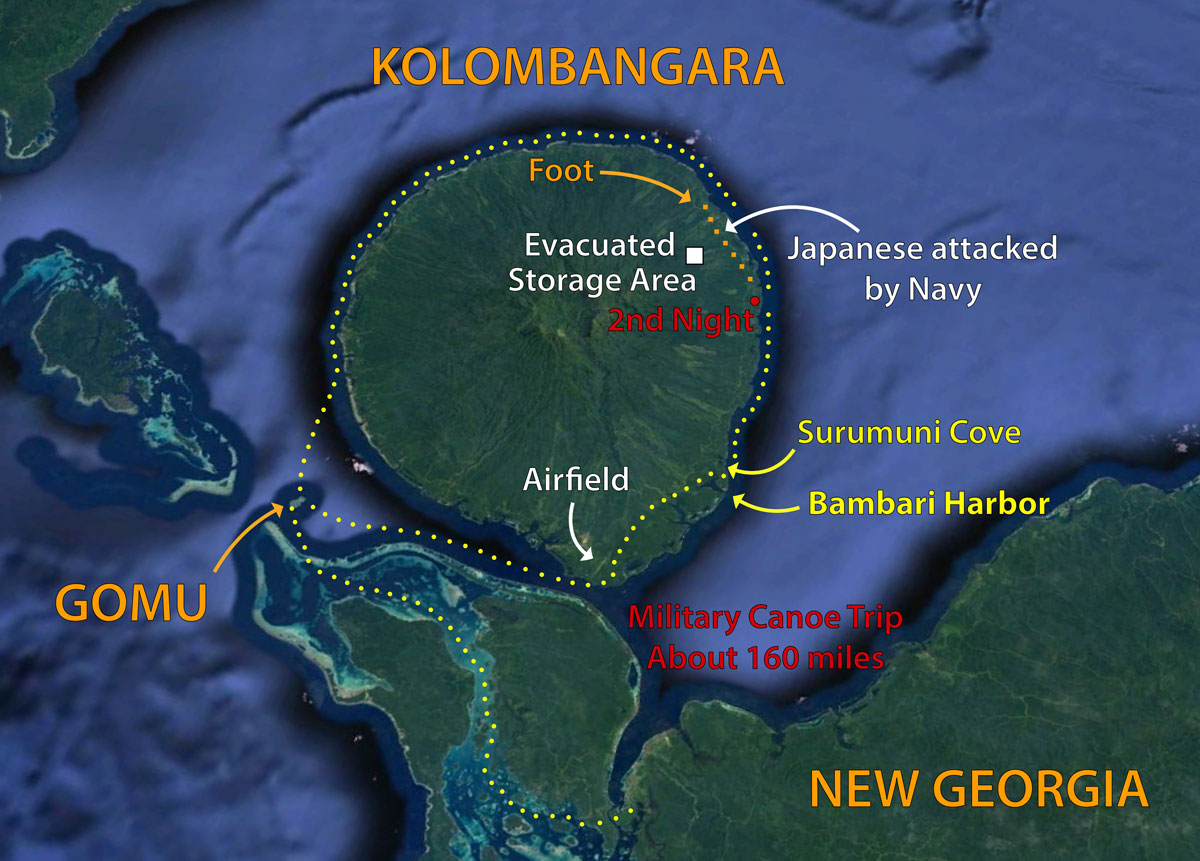

Pushing up the Coast

Now that the regiment’s flanks had been made secure, the only job left was the final push up the coast. And would you believe it, again I was given the order to provide the flank security for the regiment as it attempted to connect up with the 35th regiment, which landed on the other side of the island. It headed north and eastward in a pincer movement to establish that there was no organized resistance left on the island. This meant that the army could move northward toward the New Georgia Island.

That flank patrol only lasted for a day. We went some 15 miles over and through grass hills and jungle growth. It was so thick at times that we were forced to chop our way through with machetes.

We only encountered one pocket of tired Japanese lying about in bunkers and in hammocks. They were apparently an ammunition detail. Mortars were stockpiled next to the trail. Our mission was to protect the regiments flank as they proceeded up the coast, so we did not engage them. Our best bet was to go right through them. They had not seen us yet, so with a few hand signals, we literally ran through their camp lobbing grenades and firing our weapons into every bunker we passed. One soldier was caught in his hammock, but never woke from his sleep.

When we finally met our regiment on the coast, my muscles and legs were so swollen that I could not sit down. I had to walk about a bit to get my body to function again. Coming down from the hills we followed a stream bed to the coast, which meant we had to double up our bodies in a crouched position to get beneath the vines and vegetative growth.

The next day my platoon received its first break. We were placed in reserve in the push up the coast. There was not too much action from then on. The regiment came upon a few sick and hungry stragglers, somewhat like those we encountered the day before. As my platoon marched in file following the battalion, I came upon a wounded Japanese soldier whose skull had been partially shot off. There was no hope for him, because there were no facilities on the island for this type of wound. In most cases the medics would simply put a soldier in his condition out of his misery. I felt sorry for him and put a bullet into what was left of his brain.

Rest and Relaxation

The rest of my time on Guadalcanal was like a vacation. I did have the eastern sector of the Island to patrol, which amounted to our men going from one native village to another, visiting, and exchanging GI food for native fruit, such as watermelon, bananas, and pineapple.

We lived in an abandoned coconut plantation home. It had a complete screened porch and probably the only flush toilet on the island. Our water was obtained from rainwater that drained from the corrugated roofing into a large tank.

We were given a training schedule, but our training was getting used to the luxury of life. Every man had a bunch of bananas at the head of his bunk. There were no roads on this part of the Island because of the many rivers. We hunted for crocodiles, and when we got hungry for real food we would shoot one of the Holstein cows on the coconut plantation that the British used to keep the grass down below the coconut trees.

We barbecued roast pig and shared a cow or two with the local natives. When we finally left, the local people gave us a wonderful send off. They danced for us and beat their hollow wooden drums to show us their appreciation for clearing the Island of Japanese, and for providing them with some meat.

Heading for New Georgia

General Dalton (left) greets General Walter Krueger on Luzon, Philippines, in an undated photo.

My reprieve from combat was not to last. I soon learned that our regiment was ordered to fight the Japanese on New Georgia Island. We were to have one advantage. Our regiment was turned over to a West Pointer, Colonel James Dalton. We finally got someone who appeared to have his head screwed on properly. Unfortunately for my platoon, my combat experience came to his attention and the platoon was used again for major patrol activity.

Real Sacrifice

Next to the plantation home was a gravesite of a Catholic Nun, who was bayoneted by the Japanese after she was accused of being a spy. The Seventh-day Adventist’s and the Catholics left their mark on the Island, bringing a little civilization to these Melanesian natives who still suffered from many tropical diseases, including malaria, dengue fever, warts, and elephantiasis.

Final Thoughts

My platoon had it’s baptism by fire, and I was very proud of the men with whom I served. I felt good about myself, but in the years that followed the war I wondered whether I had always made the best decision. My platoon had played an important part in the war so far, and the rest of the company did what they had to. When the chips were down, these soldiers put their lives on the line, which many soldiers lost in defense of their country.

I learned later that private Peralta had a whole residential area of Southern California named after him, called Peralta Hills. Eddie Lorenz did survive, and Marmalejo’s memory was honored by having the Redlands California American Legion Hall named after him.

Frank Smiderly, with whom I visited years after the war, and who fought alongside me, received the Bronze Star along with the honored Infantry Combat Badge, which the other members of my platoon also received. I asked Frank to document his experiences and feelings about the war, where he played such an active part, for the benefit of those who have never experienced war, and for his posterity. He told me that he did not think anyone would be interested. I responded by telling him that his children and grandchildren should know something about the personal sacrifices their father and grandfather made, along with others, to make sure they could live in a nation of liberty and freedom. He said he would. I have sent a copy of this part of my own personal history to Frank, so he can add and build upon it. I am holding him to his word.

.jpg)

;

;