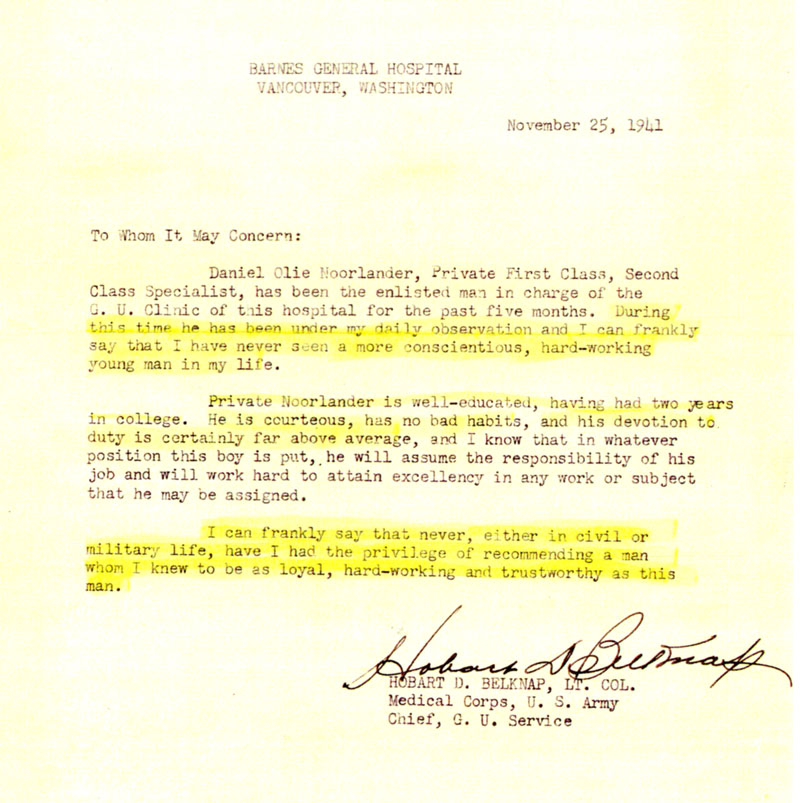

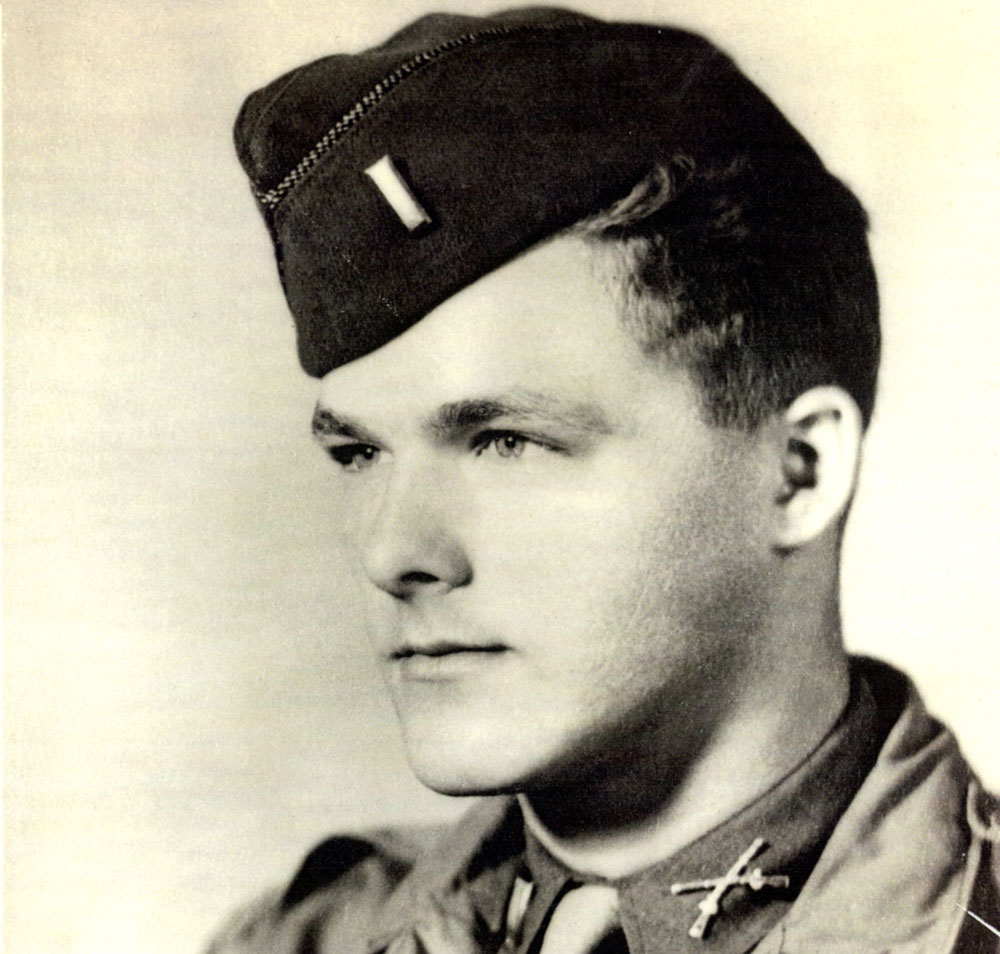

Lieutenant Dan Noorlander

March 12, 1921 — October 3, 1990

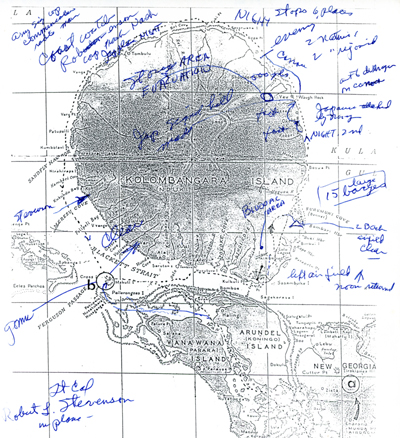

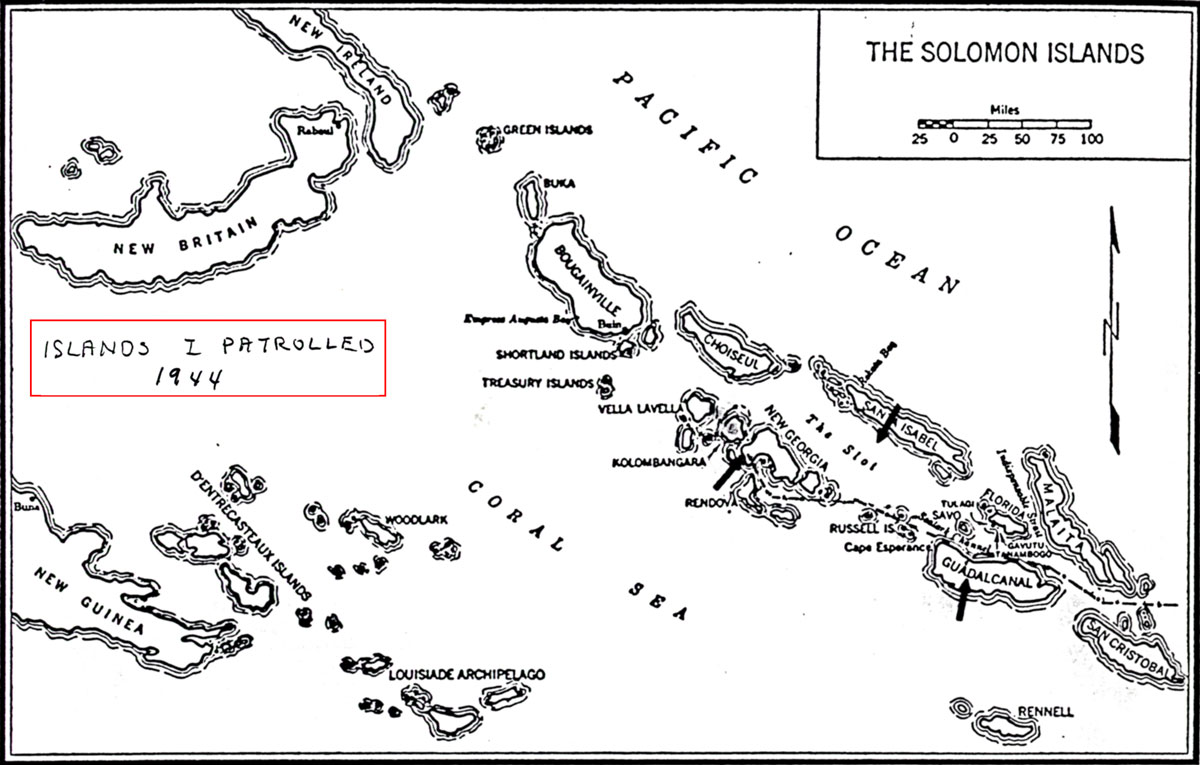

Kolombangara

Lt. Noorlander’s Account

Kolombangara Mission to Scout Remaining Japanese Positions

Burma Request

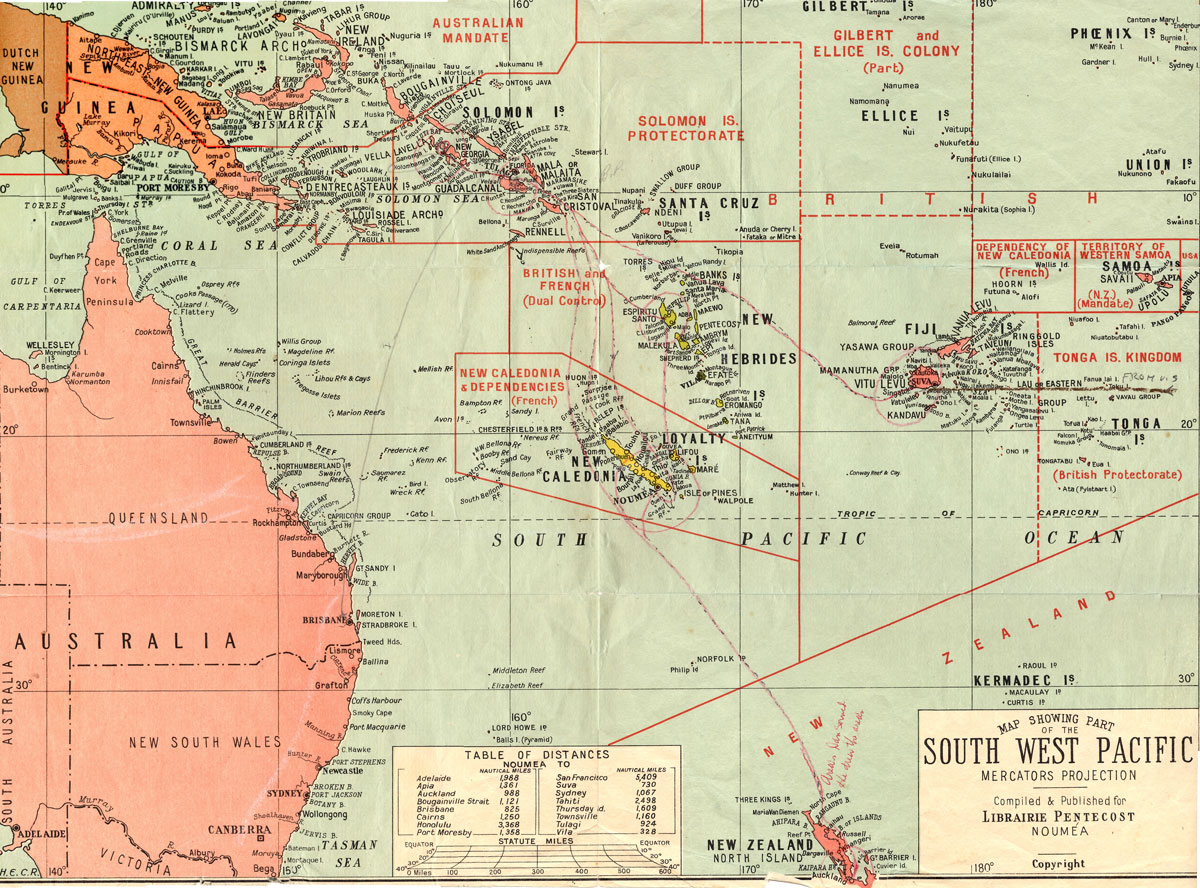

When I returned to New Georgia Island, the campaign was over. Our forces received only a few artillery shells from the area of the airstrip the Japanese built on Kolombangara, an Island about 30 miles in diameter just to the north of us.

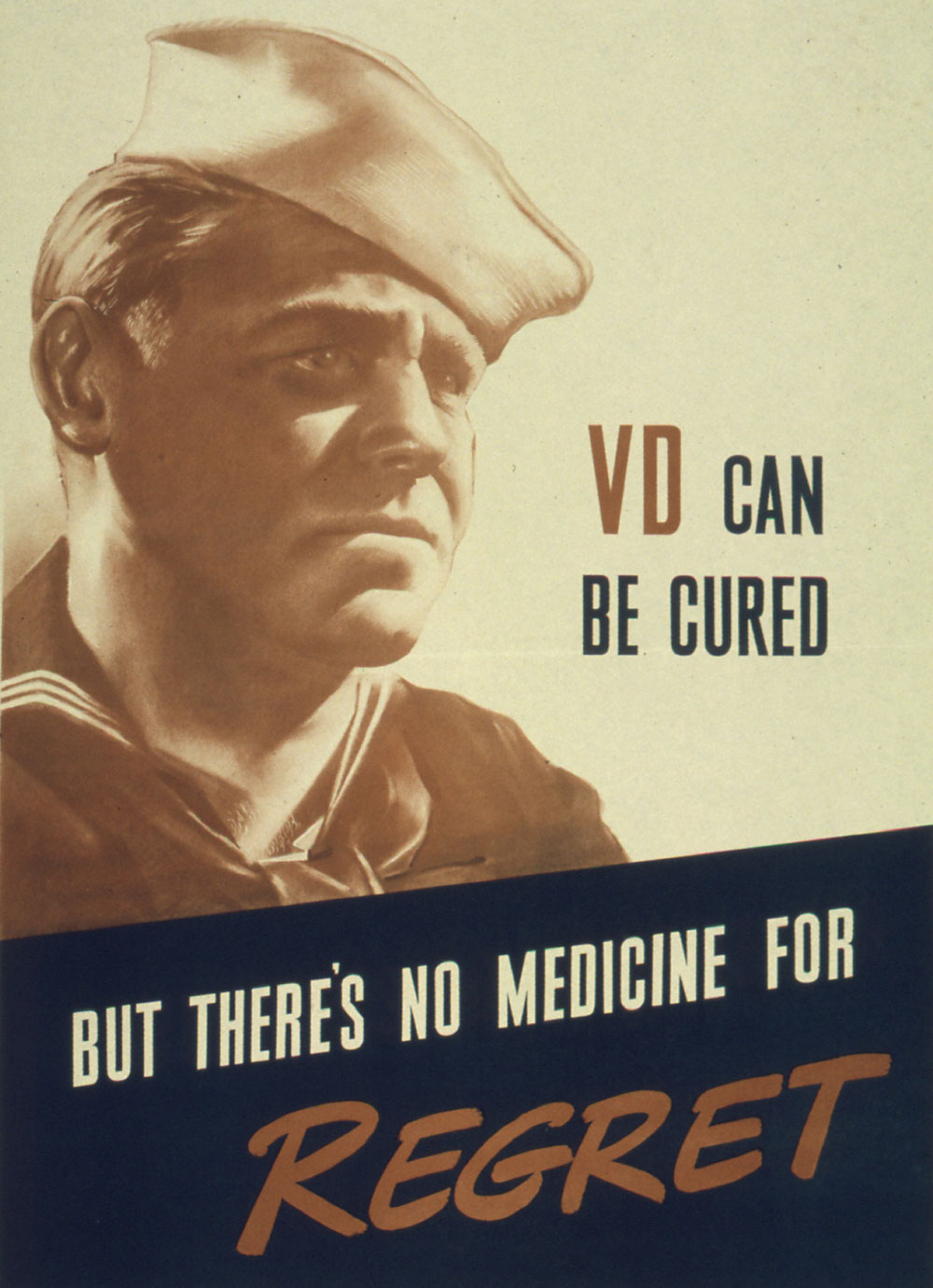

Boredom started to set in and I responded to an Army request for volunteers who had experience in jungle warfare to go to the Burma theater of operations. My high school and college friend, Warren Gin, who was Chinese, was shot down flying over Burma as a volunteer for the Flying Tigers.

Transfer Denied

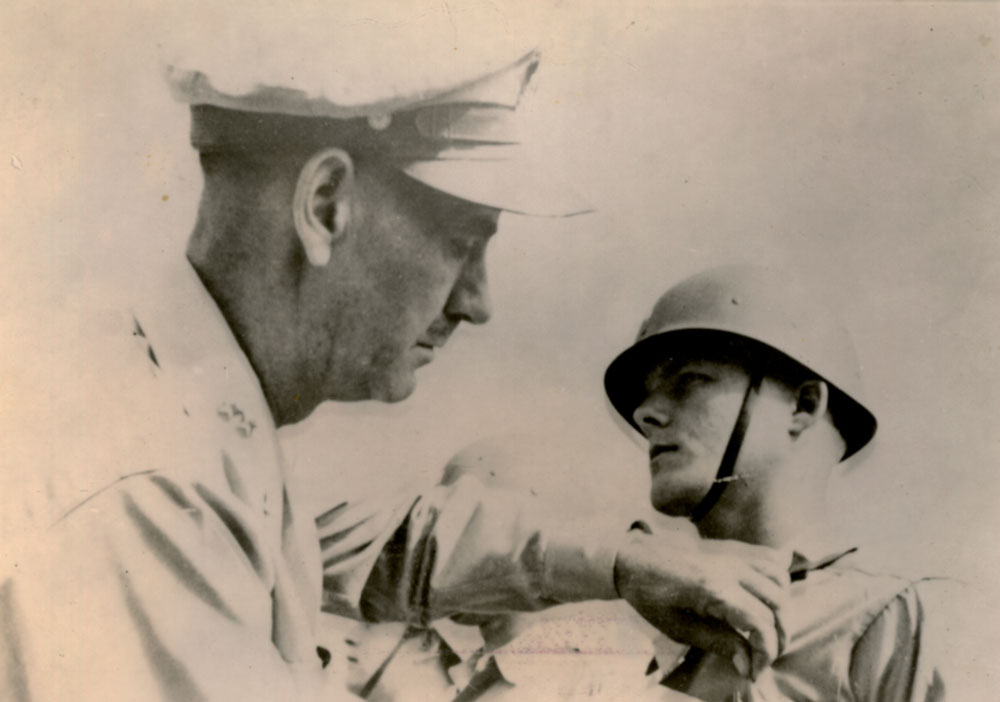

Col. James L. Dalton II, the West Pointer who took over command of the 161st Infantry, called me into his tent to talk over my request.

He told me that he wasn’t going to approve my transfer, adding: “You know, you almost cost me my life, don’t you?”

“How’s that?” I responded, trying to think back in time.

He reminded me about the time I took him on patrol. The objective was to show him the Japanese positions we spotted before I was wounded, but took only two men with us. Then I remembered. Half way to our objective we looked over a gutted valley where we caused the Japanese to expose their line by feigning an attack with a lot of firepower. One of my scouts signaled me that there was an enemy patrol lying against a large tree just on the other side of us. I signaled my two scouts to bracket the Colonel and get him back to our lines. I brought up the rear to provide cover in case we were spotted.

“Look, Colonel,” I defended myself, “you did say for me to take a “few men.” Two men are a few men to me. Would you have me take a whole company and make the bush sound like a herd of elephants?”

Funeral procession for US Army Brigadier General James Dalton II on Luzon, Philippines. 18 May 1945. Occurring shortly after Dalton was killed by a Japanese sniper during the Battle of Balete Pass.

He knew I was right, and was only trying to badger me a little. Colonel Dalton was the youngest Brigadier General in the war, moving up the ranks from Captain at Pearl Harbor in 1941. His daring cost him his life later in the Philippines.

Colonel Dalton responded with a smile and told me a story I had not expected to hear.

Earning a General’s Confidence

“Lieutenant, a few of your men came to see me while you were in New Caledonia,” he began. “They told me of your scrap with the Japanese patrol, your wound, and later how you challenged them to follow you in order to straighten out the lines. They also told me how you corrected the soldier that panicked.” He hesitated then said, “They must think a lot of you, because they recommended that I give you some sort of medal, and I agree. Consequently, I have recommended the Distinguished Service Cross for you, and want to thank you for what you did.”

Thinking back, I do not know what really made me feel better—the medal or the half-tin of sardines one of my men gave me. Both were acts of kindness and consideration. Up to that point I didn’t even think in terms of medals. I thought that what I had done was only a by-product of what I was trained to do. There really wasn’t much else I could have done and still lived with myself. I had seen so many acts of courage by men who literally laid down their lives for a buddy, or exposed themselves to unnecessary fire just to pull someone out from the exposure of enemy fire.

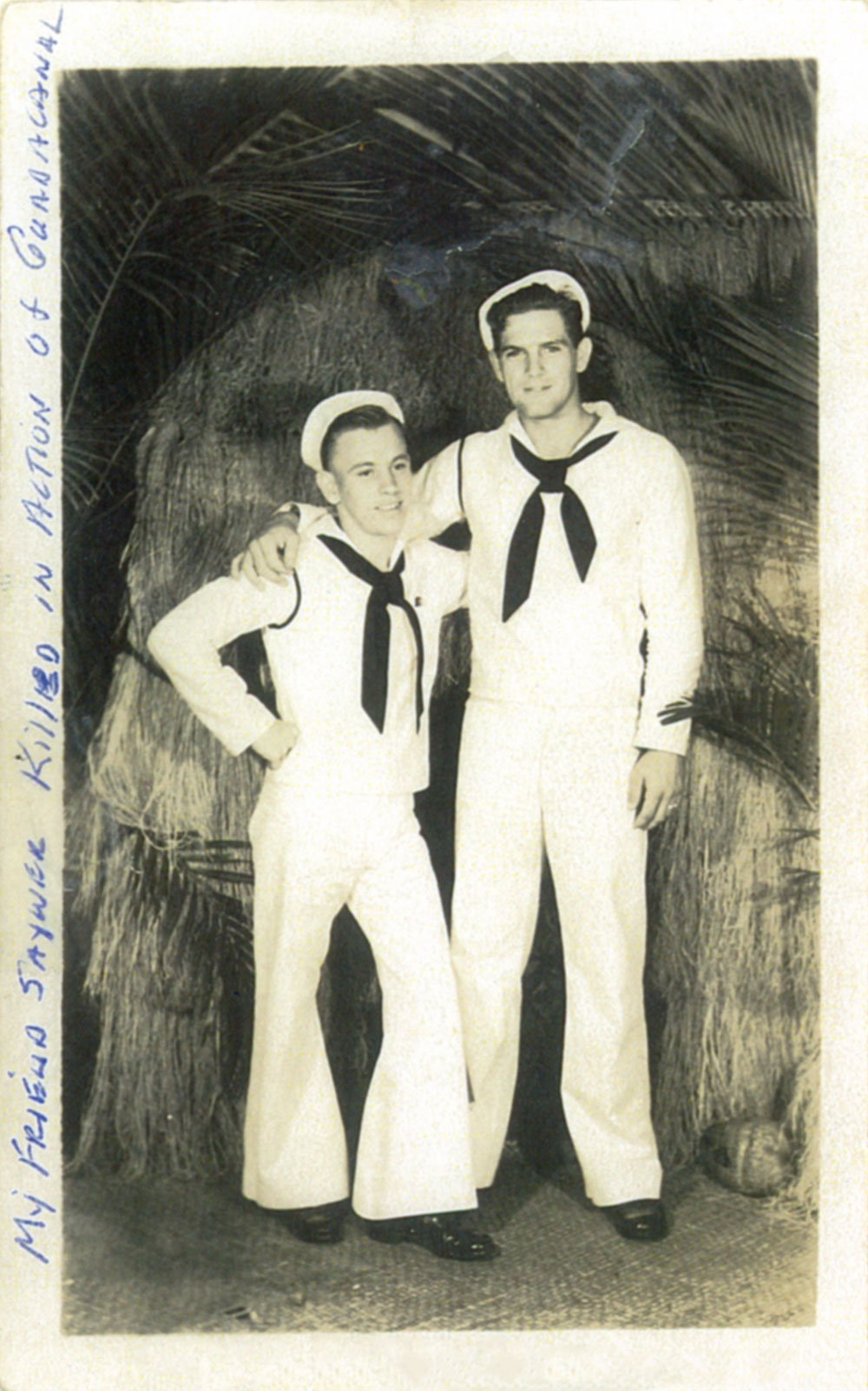

Tragedy Not Forgotten

These are the things that make men close to each other in combat. The Lord Himself stated something like this, “Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends (see John 15:12-13). War, I suppose, is one of those great learning experiences. It forces you to make decisions that make you like yourself or not. Frankly, I felt good about myself, but often wondered about those times when the decisions I made ended up in tragedy for someone else.

Such a time was when I came upon a Japanese soldier on Guadalcanal, standing against a rock with eyes closed and cupped hands folded in front of him. I asked him to surrender, but he did not move. I suspected that he held a grenade in his hands, and could not take any chances. When he moved his hands, I stepped back and ordered him shot. When he fell forward, he did not have a grenade. He was just too frightened to respond to my poor Japanese. I have had to live with that decision all my life.

Change in Plans

Colonel Dalton then proceeded to tell me that instead of Burma, I was recommended by a Lt. Ferriter from the 27th Infantry to go on a patrol with him to Kolombangara. The mission was to find out where the Japanese lines were. “Time is critical, Lieutenant! Consequently, you will proceed with Lt. Ferriter on board a submarine, which will land you there. This is if you agree to go.”

The next morning I received a call from Lt. Ferriter whom I had not met. He knew me only by reputation.

He started out by asking, “How would you like to go to Kolombangara with me?” “Well,” I said, “I don’t have anything else to do.” My heart started to pound a little just as it always did when I knew I had to go on patrol.

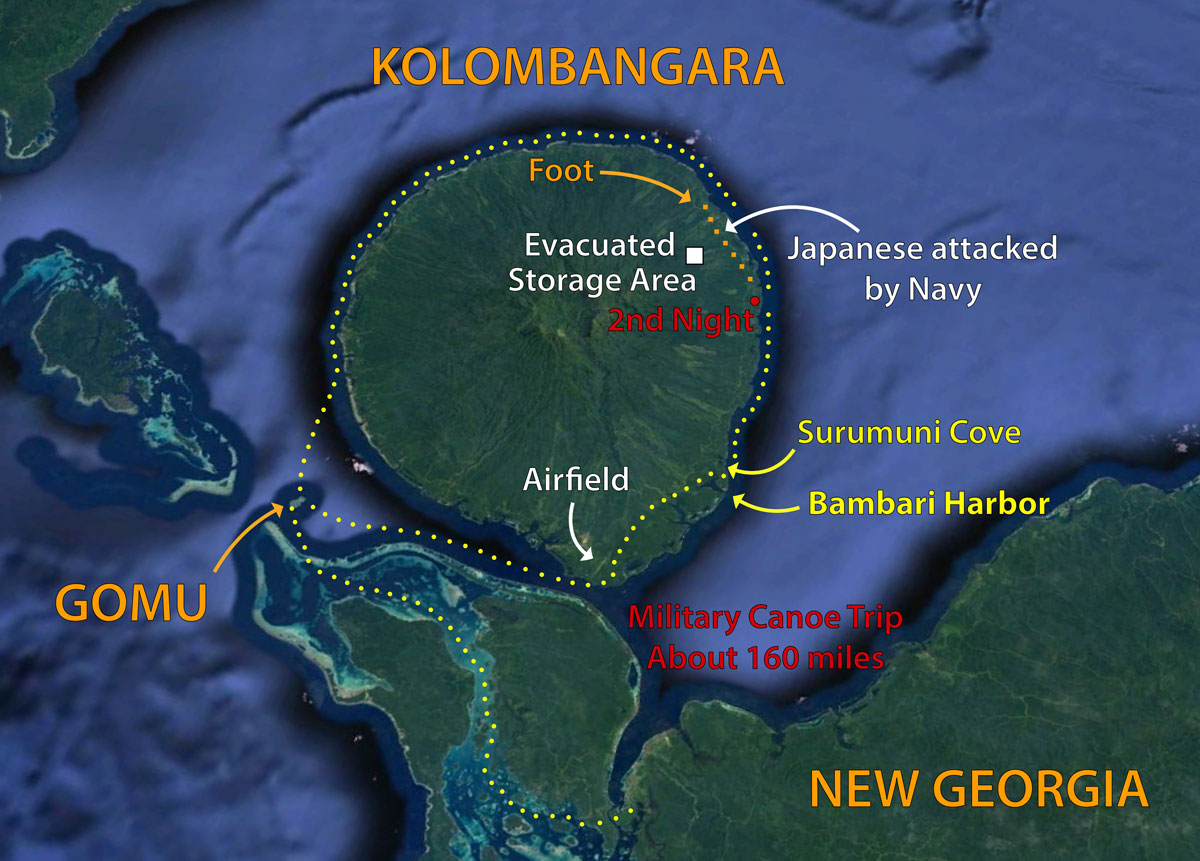

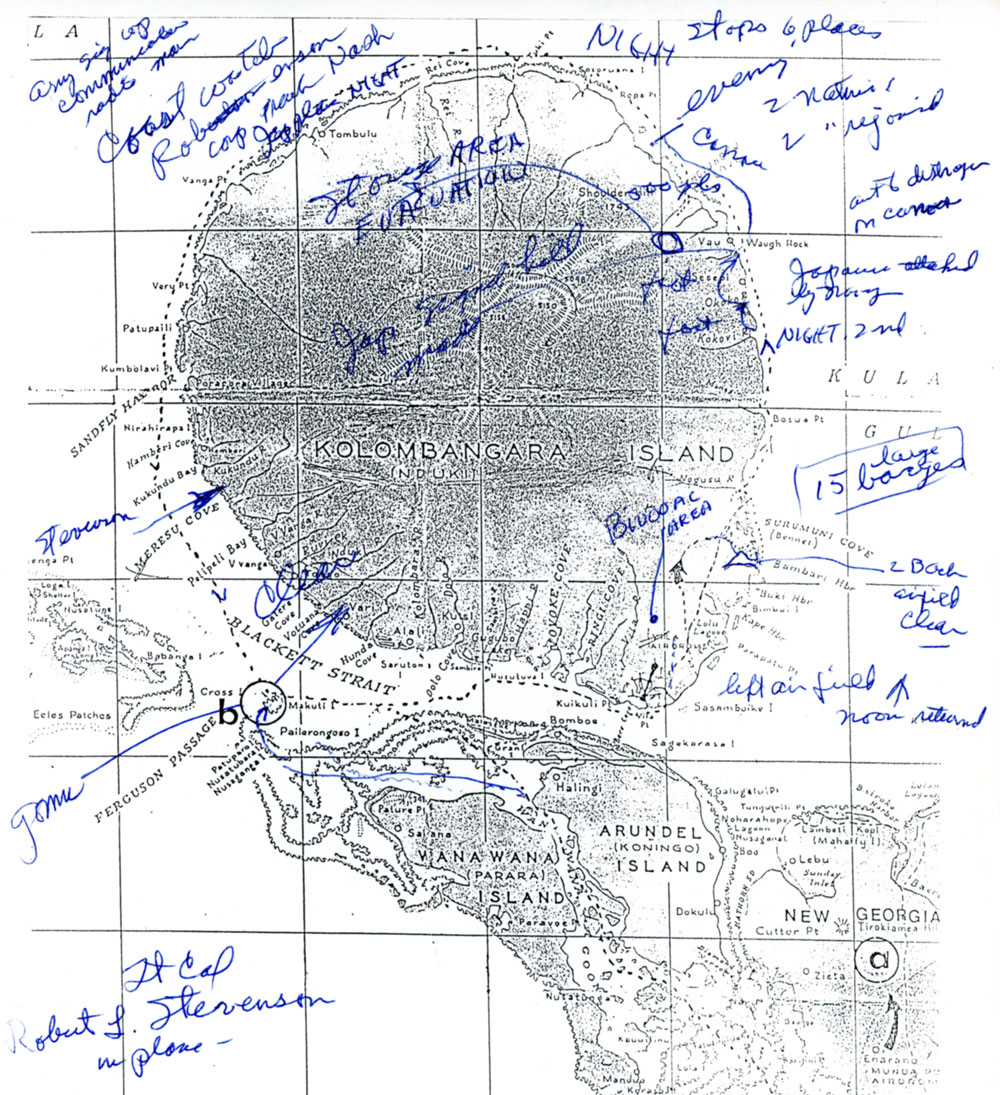

“Good”, he replied. “But there’s been a slight change.” The 14th Corps Intelligence G2 had already briefed him that a submarine was not available. “We can’t get there by submarine, so we will travel by canoe, leaving New Georgia this afternoon. We will make contact with the coastwatcher on one of the small offshore islands of Kolombangara. Can you get ready?”

After some planning, I readied myself with some suggested rations which consisted of light C rations, some rice tied in a sock, and an automatic carbine. Two canoes had been arranged for native Melanesians who would do the paddling. The only other GI would be a corporal who knew communications and would work with the coastwatcher if necessary. Ferriter would take the lead canoe and I the rear. We carried palm leaves in the canoes to hide under just in case we were spotted. We also took a few green coconuts for a fresh water supply.

Gomu Island

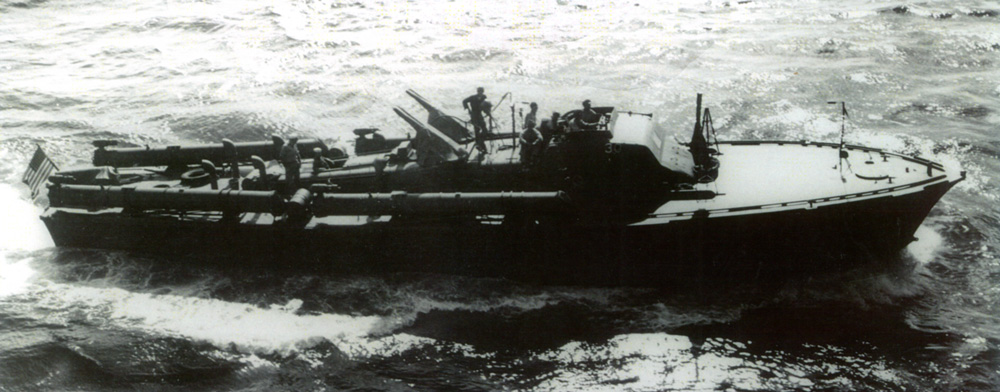

We timed our departure to land on the small Island of Gomu where we would meet the coastwatcher. I learned after the war that this was the Island President John F. Kennedy, who was a Naval Officer, stayed on after his Navy PT boat was wrecked on August 2, 1943. It was only a few hundred yards long, with a small native hut to house the radio the coastwatcher used to inform our forces when Japanese planes or other activity went on in the area.

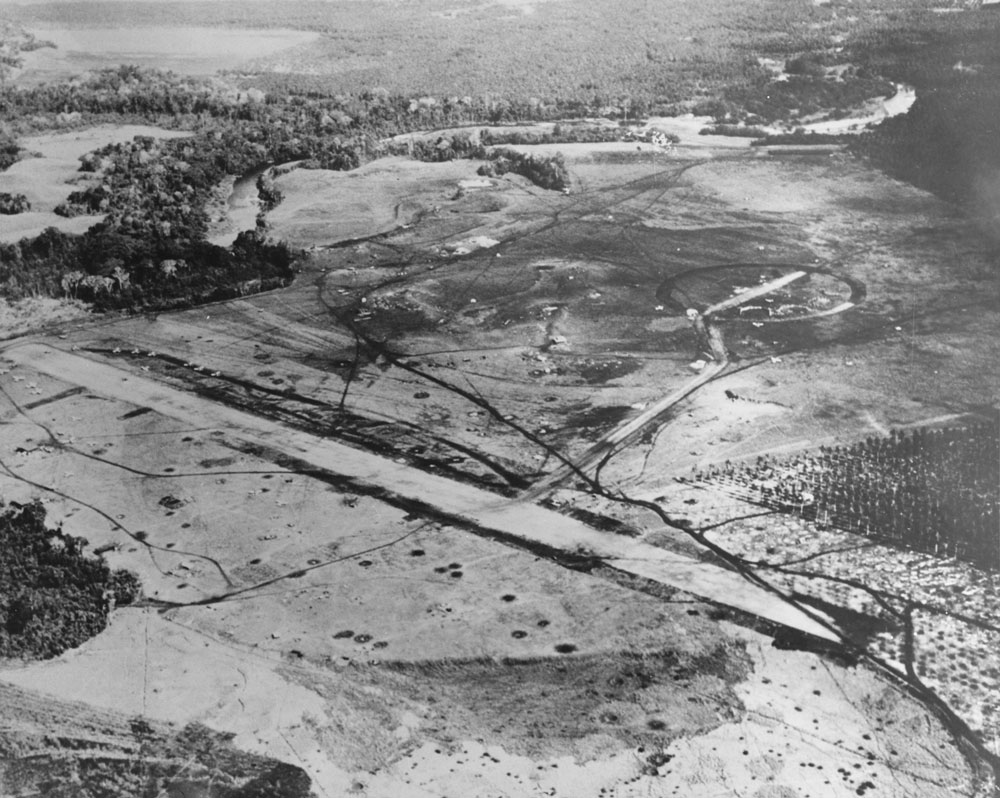

After arriving on the Island that evening, we learned that the Navy had napalmed the north end of Kolombangara. It appeared that the Japanese were attempting to evacuate the Island. We were asked to proceed with caution, but with haste. Lt. Ferriter decided to leave that night so we would land at the Japanese airstrip, instead of safer area that a short distance before the coconut olantation where the Japanese built the airstrip.

While Lt. Ferriter was going over the maps inside the hut, I was outside on the beach vomiting the rice I had eaten. I was sick and coming down with malaria. The preceding few weeks were spent in New Caledonia where there was no malaria, but I didn’t take my atabrine antimalarial tablets. I was now paying the price, but knew I had at least two days before a new cycle would hit me.

I still remember the small hermit crabs that feasted on the small grains of rice that lay on the edge of the sea water, but my thoughts were interrupted as Lt. Ferriter came out of the hut and told me that it was time to depart.

First Night on Patrol

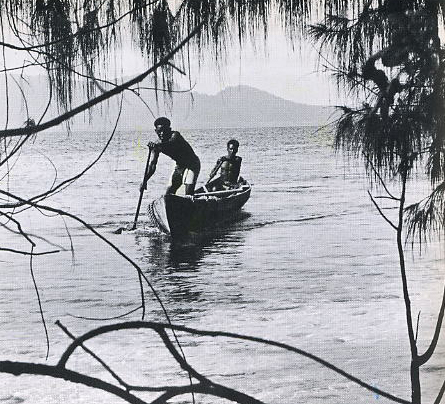

We started out in two canoes, with Lt. Ferriter in the lead. I brought up the rear. Each canoe was paddled by two native British Scouts.

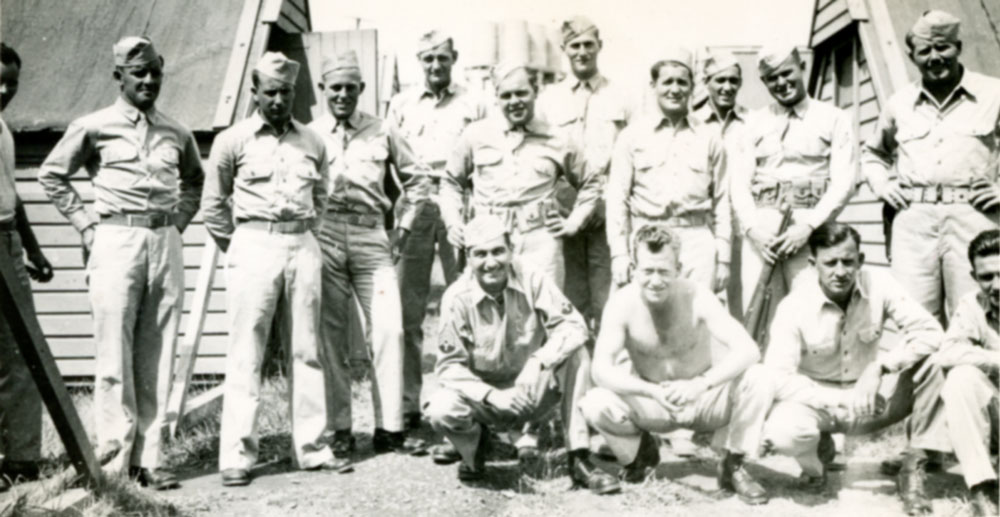

The natives who discovered Lt. John F. Kennedy and his crew on Olsana Island (3½ miles west of Gomu Island), pictured as the crew first saw them. Lt. Noorlander, who saw the show on PT 109, later wrote: “Even the native canoes and paddles were exactly as I remembered them.” Kolombangara Island is pictured in the background.

Just as light broke the skyline, we approached the beach in front of the Japanese airstrip. Coconut trees along the shore did provide us with some concealment from the interior. We gave instructions to the natives for the next day. They were to meet us up the coast from the airfield. We never entertained the thought that we might not make it.

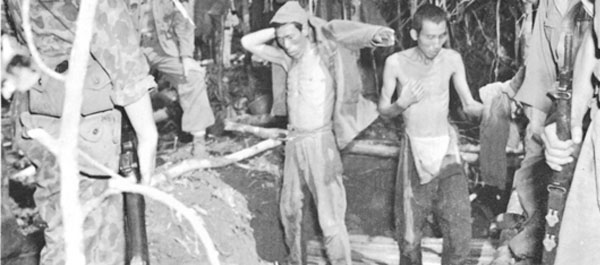

One of the native scouts remained with us, and said that there appeared to be one or two Japanese on the other side of the runway. It was apparent from what we saw that there could only be a few stragglers in the area.

The Japanese abandoned the artillery piece that had pounded New Georgia. Foot and heel prints filled with water from the previous night’s rain, and spider webs that blocked some trails, suggested that the Japanese had left the night before.

We dug into marked but shallow graves for evidence of buried military equipment, which would give us some insight into the haste of their departure. A pungent smell gave us our answer, so we closed the small hole.

We dismissed the apparently sick stragglers on the other side of the runway as harmless, and proceeded to head northward on a trail that led inland along the coast. We saw discarded field packs, ammunition, and abandoned tents still standing. Cans of tuna were still unpacked in cases, which told us the Japanese departed in haste.

Our patrol was preceded by the native Melanesian. His only weapon was a machete. He hoped to fool any Japanese he might encounter that he was just a local. Lt. Ferriter followed, then the corporal whose name I have forgotten, and myself. We had already spent the good part of the morning, first traveling very cautiously and then more aggressively. We saw evidence that there was a general abandonment by the Japanese of this part of the Island.

Second Night on Patrol

When we reached Bambari Harbor about ten miles up the coast it was already starting to get dark. We saw some smoke on the coast suggesting a campfire. We decided to get some rest and sleep before proceeding with the investigation the next morning.

We slept alongside the trail wrapped up in a shelter half, burying ourselves in the green foliage. I became aware of a mass of flies that covered the lower side of the leaves. Some of them fell on me and I brushed them off my face.

We got up early the next morning, but the people who made the fire were gone. By then the natives arrived with our canoes. The small harbor was partially hidden by dense foliage and trees. Inside the harbor were about 15 barges and a sailboat which we decided to investigate. In the sailboat we found numerous documents and maps of the area left by the Japanese military. Later we turned the documents over to army intelligence.

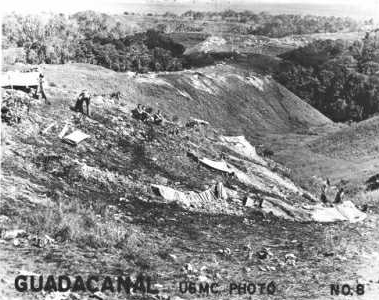

Kolombangara Island with impassable coast.

We decided to go a few miles into the interior, since the coast was impassable by foot. We told the natives to pick us up at Surumuni Cove, where we got into the canoes and headed northward to make better time. There were no Japanese in this area.

Two Navy planes passed over us and tipped their wings. On their second pass we signaled to them that the area was clear. A Lt. Colonel Stevenson waved to us in an attempt to point out the rather large sail boat in the cove that we had already investigated. We waved them on and they tipped their wings in acknowledgment.

Third Night on Patrol

We passed a beached Japanese destroyer that was burned and gutted by our Navy. We boarded it, but there was nothing left of military value so we proceeded northward again. We went inland every so often to make sure there were no organized Japanese forces. We slept the next night near the coast.

Around noon the next day we spotted what appeared to be a man-made signal tower along the coast, which we stopped to investigate. Slightly inland we found what we were looking for—the Japanese evacuation and storage area. They left behind at least 500 piles of military equipment, which meant the Navy had done a good job. The Japanese soldiers who were not bombed apparently had been evacuated northward to another Japanese held Island.

Final Night on Patrol

For the remainder of that day and through the next we canoed around the rest of the Island, turning inland about a half dozen times to make sure there were no Japanese. We arrived the next day at Gomu Island, where we radioed our findings and headed for home. We were gone three and a half days.

A General’s Commendation

We were debriefed at New Georgia where the brass gave each of us a pint of whiskey. I didn’t drink, but thanked them anyway. I knew that I would find someone to enjoy the whiskey, which didn’t bother me. It was better the soldiers drink whiskey than the rot-gut some of them were drinking.

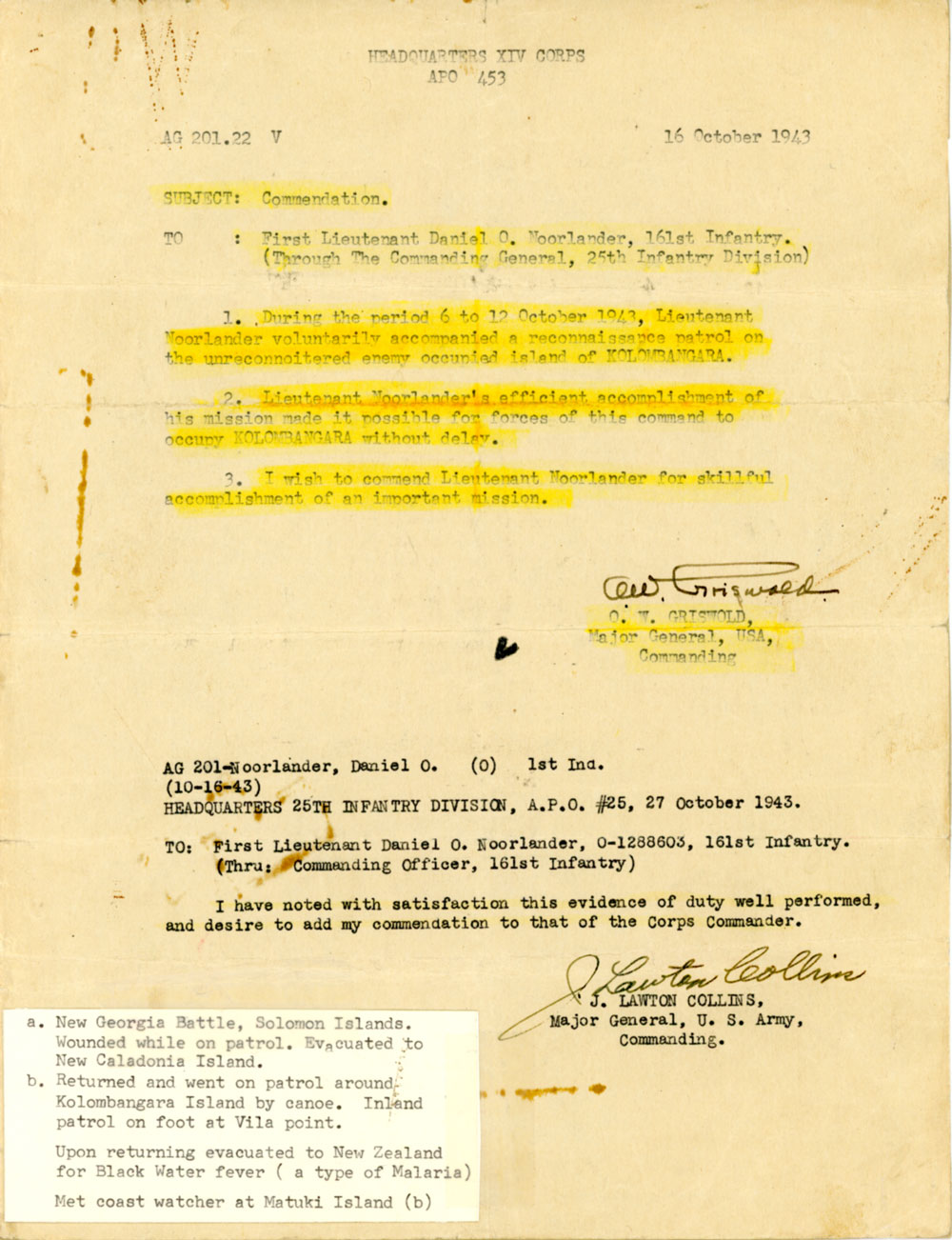

My reward besides the whiskey was a commendation from the Commanding General which read:

1. During the period of 6 to 12 October 1943, Lieutenant Noorlander voluntarily accompanied a reconnaissance patrol on the unreconnoitered enemy occupied island of KOLOMBANGARA.

1. During the period of 6 to 12 October 1943, Lieutenant Noorlander voluntarily accompanied a reconnaissance patrol on the unreconnoitered enemy occupied island of KOLOMBANGARA.

2. Lieutenant Noorlander’s efficient accomplishment of his mission made it possible for forces of this command to occupy KOLOMBANGARA without delay.

3. I wish to commend Lieutenant Noorlander for the skillful accomplishment of an important mission.

Signed

O. W. Griswold,

Major General, USA,

Commanding

Blackwater Fever

That afternoon after being debriefed, I returned to my outfit. I was deathly sick with a type of malaria called Blackwater fever. During the last day of the patrol around Kolombangara I was out of it mentally. Years later, my friend and retired Colonel Ferriter, who at the time was Lt. Ferriter, filled in the details of our trip around Kolombangar. I was sick during the last part of the trip, and didn’t remember everything that went on.

He told me that Lt. Colonel Stevenson received the Bronze Star for killing a Japanese soldier on the western side of the Island two days after we returned. On the same day, one of our infantry regiments landed on Kolombangara after U.S. forces softened up the landing strip with heavy shelling. Either the army didn’t believe our report, or they were going through a training exercise, or they were just making noise for the folks back home. After my experiences in Korea several years later, I am inclined to believe it was the latter.

Out-of-Body Experience

Because I was so sick, I was evacuated to New Zealand where I was united with my old platoon, which fought with me on New Georgia Island. I had almost forgotten what civilization was all about. I had already spent eighteen months in combat and living in the jungles of the Solomon Islands.

After the mission around Kolombangara Island, Lt. Noorlander was evacuated to New Zealand with blackwater fever. Here he is pictured in New Zealand with an unknown buddy.

My body was weakened and I was still recuperating from my bout with blackwater fever and general fatigue, when I experienced my spirit leaving my body. Some people refer to this as an “out of body experience,” which has been well documented by many people.

I remember clearly how surprised I was when a nurse walked by, but didn’t pay any attention to me as I stood alongside my bed. When I looked down I could see myself lying in the bed. I wanted to get back inside my body, and was a bit frightened at the thought that this may not be possible. The fear abated when I felt life coming back into my body—first in my toes which I found I could wiggle and then into the rest of my body.

Except for the time when I had to stick my pick-mattock into the side of the cliff overlooking the Metanikau River on Guadalcanal, to keep from falling to my death, I do not remember experiencing anything close to death while I served in the South Pacific. Now I recognize that death, after all, is nothing more than the separation of the spirit from the body.

After I regained my health, I returned to the 25th Division in New Caledonia, which had been sent there for training and to recuperate during the spring and summer of 1943.

This is my best recollection of the Kolombangara mission. Having been an infantry platoon leader on reconnaissance and combat patrol duty during most of my time in the infantry, I didn’t become acquainted with command officers above the rank of a company commander. Seldom was I ever briefed or made aware of the overall combat situation in the Solomon Islands.

Lieutenant Ferriter

Colonel Ferriter with his wife, visiting Dan and Dorothy in Salmon, Idaho, many years after the Korean War.

Years after the war I renewed my friendship with Lt. Ferriter who was four or five years my senior. He graduated from Officers Candidate School at Fort Benning a month or two before I did. He was assigned to the Regimental Intelligence or S2, so was pretty well acquainted with most of the brass. As far as leading men into combat goes, Lt. Ferriter had many of the same experiences I had. Dick, who retired as a full Colonel, filled in the blank spots of my memory about Kolombangara.

Dick was very dedicated, and a brave soldier who understood what was involved when following the infantry motto “follow me.”

On the Kolombangara patrol, it was understood that Dick was to lead out. He told me that my position as number three man in the patrol was perhaps the most dangerous because Japanese snipers usually let the leader pass under him before picking off the rest of the patrol. I knew better. I also knew that a patrol leader had to be up front where proper command decisions could be made if there was enemy contact. This was Dick’s way of making those under him feel their assignment was also important.

Richard H. Ferriter died 2½ years after Lt. Noorlander on April 23, 1993. He is buried in Arlington National Cemetery Section 66, Arlington, Virginia, United States.

You can view his burial record on the BillionGraves website.

Lt. Ferriter’s account of Kolombangara filled in the “blank spots” of Lt. Noorlander’s memory.

.jpg)

;

;