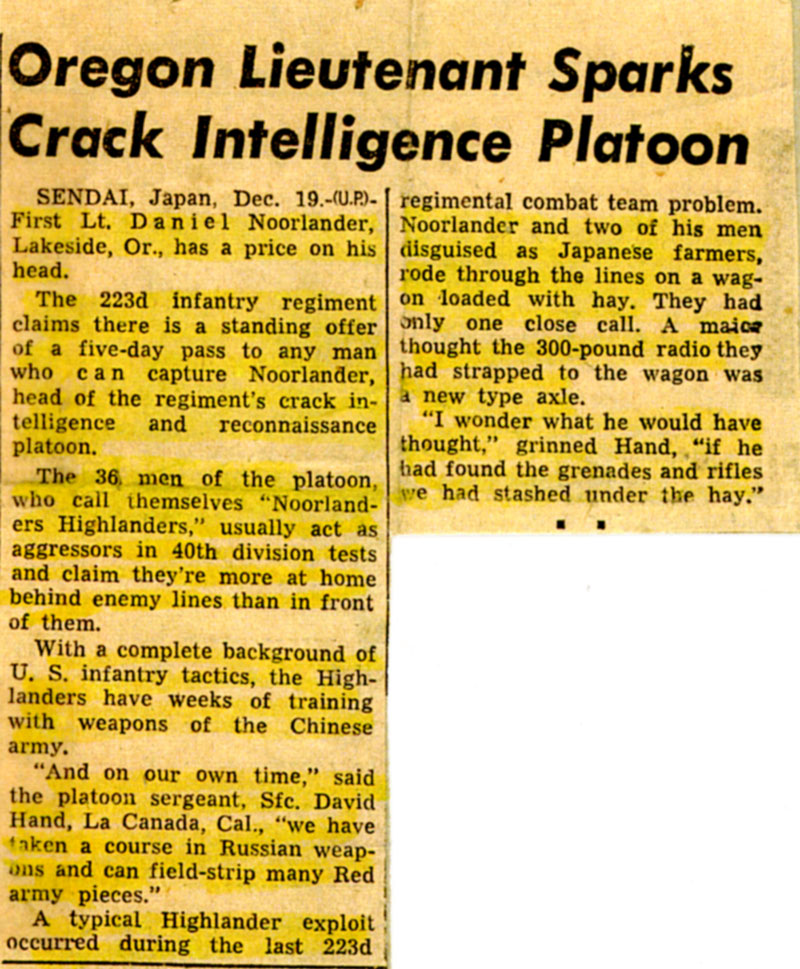

Lieutenant Dan Noorlander

March 12, 1921 — October 3, 1990

Japan

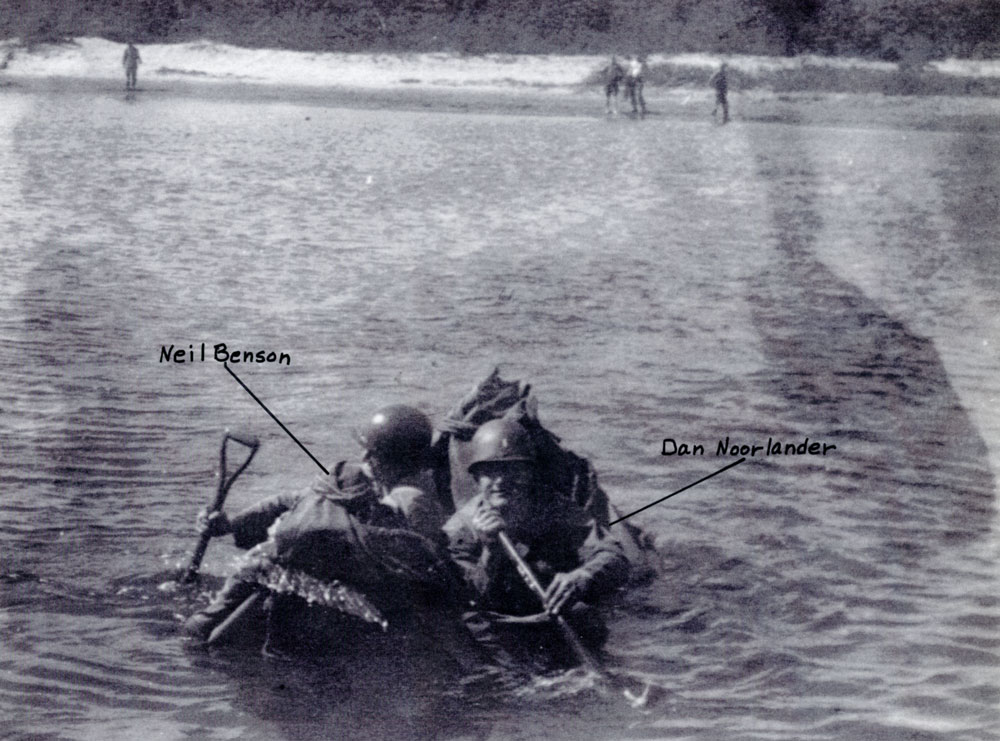

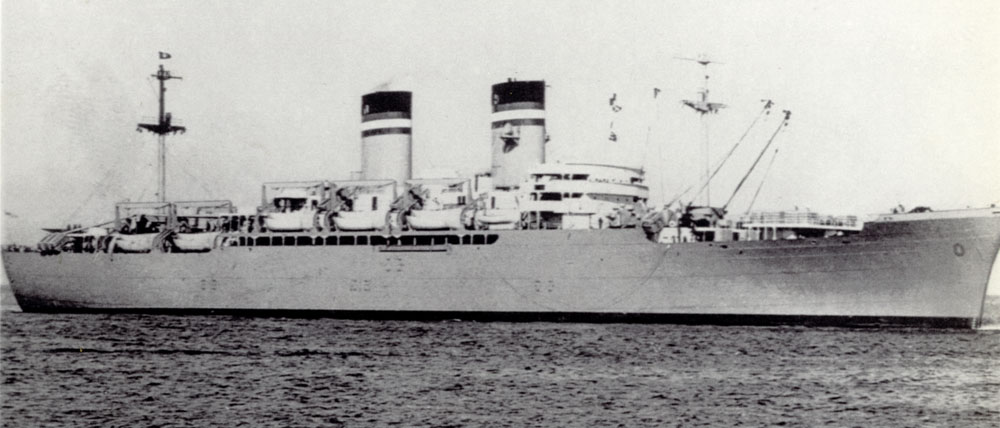

The USS General M. C. Meigs transported Lt. Noorlander to Japan for training before going to Korea. Dorothy received this picture from Sgt. Monte Rubin, June 22, 2002.

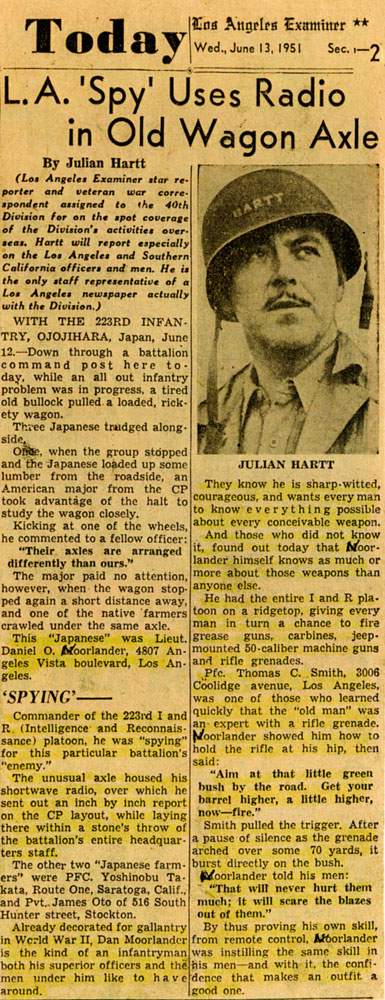

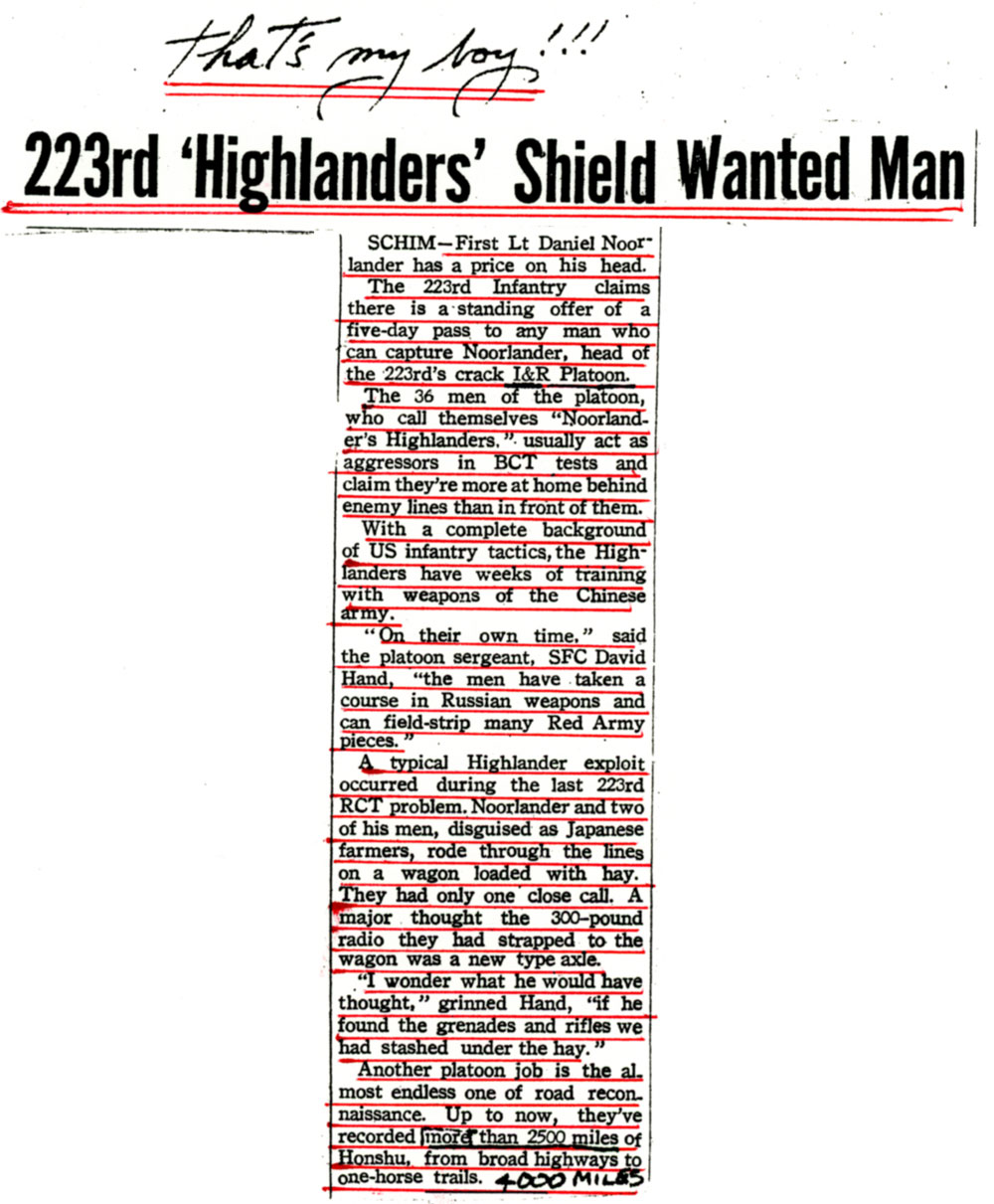

In 1951-1952, soldiers heading for Korea received intensive training in Japan before going into combat. Because of his experience in World War II as a platoon leader in the Solomons, Lt. Noorlander started out training troops in California (USA).

Discovering this wasn’t for him, he requested a transfer to the war front, which is how he ended up in Japan. His platoon, leading by example, became known as “Noorlander’s Highlanders” for their effective training maneuvers.

Lt. Noorlander’s Account

Poor Leadership is the Agent of Moral Misconduct in War

Before Enlisting

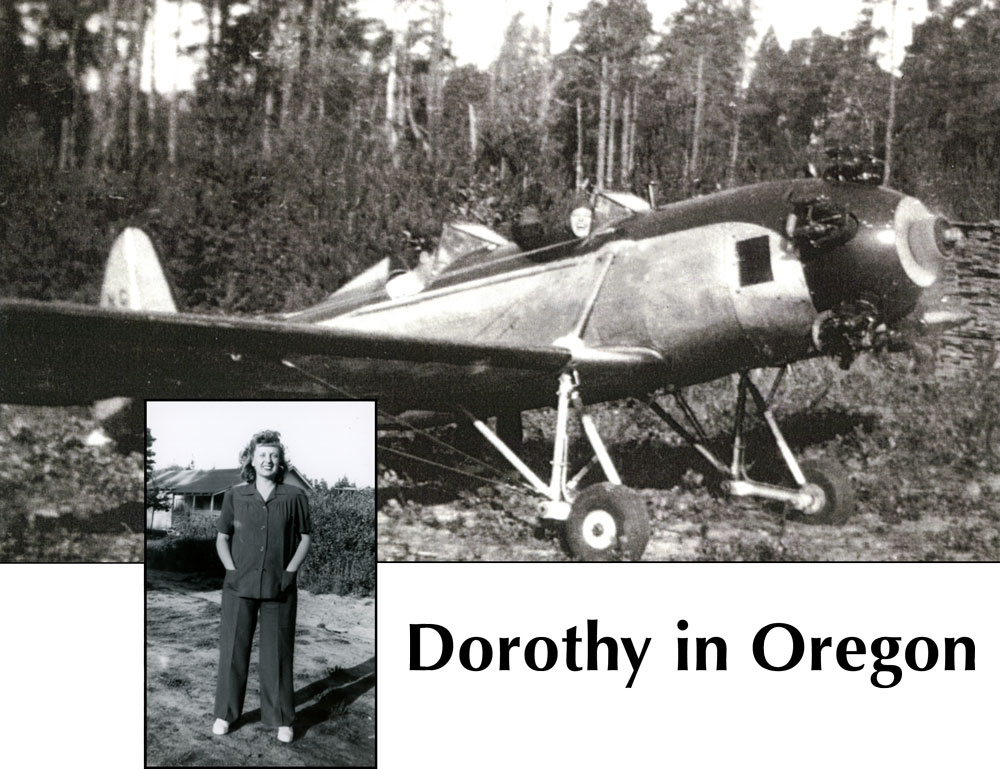

I went to work for General Mills after I graduated from College. It gave me experience, but it wasn’t what I wanted to do with my life. We moved to Oregon where we purchased a dairy farm and logging operation with my family. Even though Dorothy and I shared the down payment with my father and brother from accumulated army pay, it didn’t turn out to be a partnership farm operation. We didn’t earn an income on the ranch because everything went to pay off the mortgage.

Dorothy in Oregon, eight months pregnant.

The war in Korea was going on, so I enlisted as a way to support my family. When my orders arrived, I was happy to leave this lonely spot in the woods where the only access to the city was by boat. Dorothy was pregnant and wanted to go back to California to have the baby, so it was a good time to make the change. Being a soldier was something I knew about, and the way I could serve both my family and my country. I was away for the next fourteen months.

Military Service

I was first sent to Camp Roberts to train troops. It only took about two weeks before I decided that rear area army life was not for me. I asked for a transfer to Korea. My transfer was accepted.

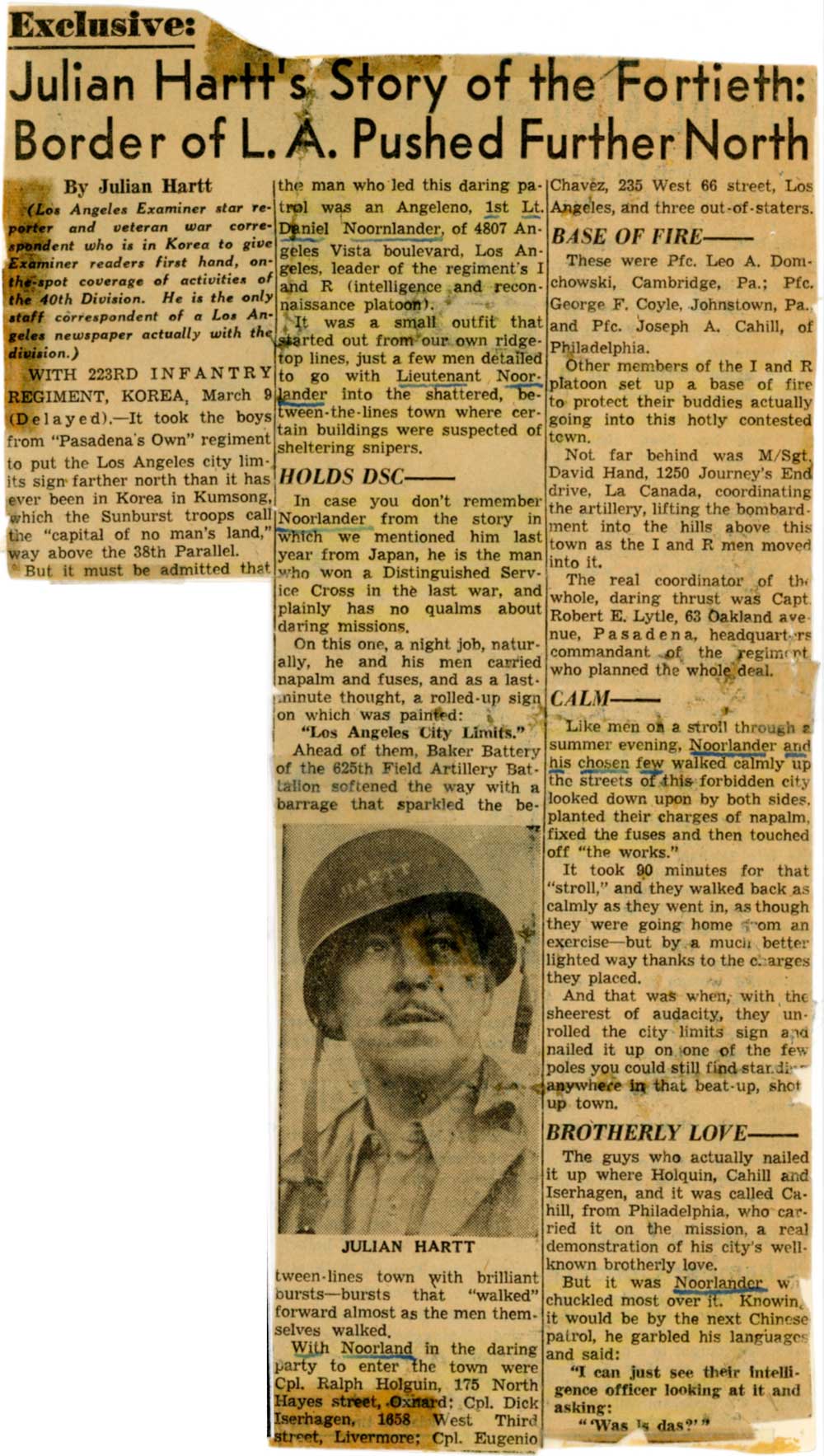

I ended up in Japan with the 40th Infantry Division, assigned to the 223rd Infantry Intelligence and Reconnaissance platoon. This was the only combat platoon of the headquarters company.

Lt. Noorlander: “After a hard days work. Me sitting on bumper of the jeep. Ojoji Hani area in Japan. I & R Platoon. August 1951. Getting ready for Korea.”

We spent the following months training near Sendai, Japan, in preparation for the war in Korea. I discovered that the leadership of the 40th Infantry Division had about the same mentality as the leadership of the 161st Infantry Division in the Solomon Islands (World War II). Combat and experience turned things around a bit.

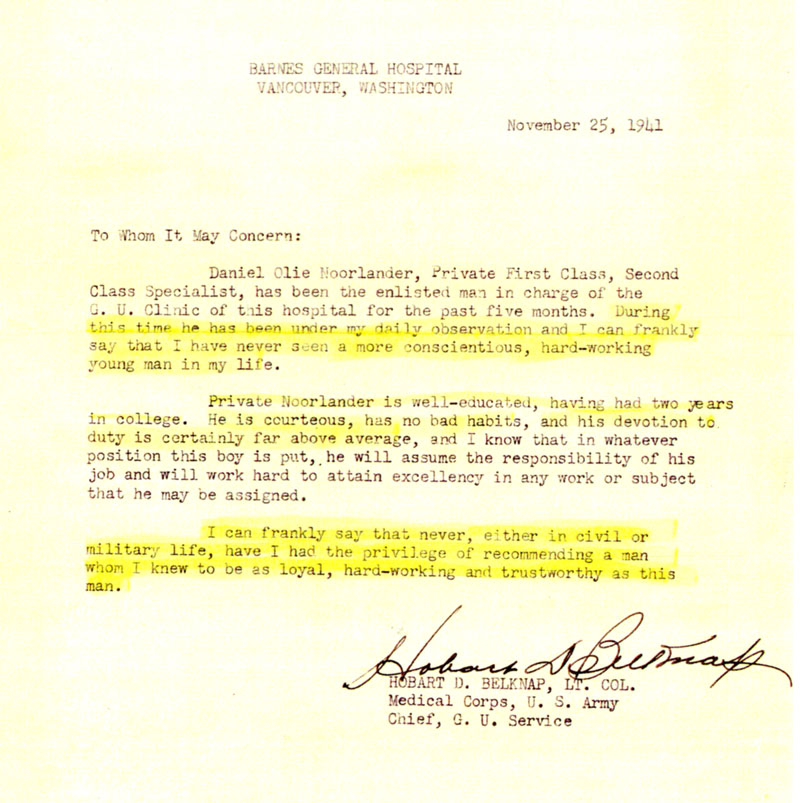

A Moral Problem

Most of the company commanders wanted to appear to be good guys to their troops. They decided that providing company parties was the best way to boost the men’s moral. The parties consisted of an issue of Japanese beer supplied in barrels to the company mess halls. They also provided their own version of a USO show by hiring prostitutes to perform strip shows for the men. After the men’s brains were stimulated and numbed sufficiently, they were allowed to visit the whore houses in Sendai. The by-products of this stupidity soon manifested itself in a division wide venereal rate of over 80 percent. If it were not for the newly discovered penicillin, the consequence to the division would have been disastrous. I only remember too well the suffering and mental problems of those GIs at Barnes General Hospital when I was an enlisted man during World War II.

From the division commander on down, the behavior of the commissioned officers suggested a court martial for almost all of them. The General, probably at the taxpayer’s expense, imported his girl friend from the states. All the hired help, including the cooks, were Japanese prostitutes that lived openly in the barracks with the GIs. Often a soldier had to step over them before he could get to his own bed.

Company officer’s bragged about their exploits in local brothels. The next day they were so exhausted, they were incapable of carrying out their responsibilities. Every morning at sick call there were hundreds of GIs waiting in line for a penicillin shot. Unfortunately, a small percentage would never be cured. Even penicillin could not take care of all the infections spread by sexual contact.

Standing Against Evil

We had division meetings concerning the articles of war that had to be taught to the men from time to time. At one such meeting of commissioned and non-commissioned officers, the meeting turned out to be a recitation of pornographic jokes by the teacher, a division Captain.

I and Chaplain Nelson, a friend of mine, walked out of the meeting. I went to company headquarters and looked up the article of war concerning this type of activity. I turned in my resignation as a commissioned officer, with the explanation that I felt I could no longer prepare the men under my command, nor could I lead them into combat with the mental and physical handicaps imposed upon them by the leadership of that division. At the bottom of the page I gave notice that a copy of my resignation would be sent to my congressman. I sent it through channels.

The response was fast. The Colonel who was in charge of the meeting offered me his apologies. He asked me if I would change my mind, if he offered the whole division an apology. Apparently he had second thoughts about his leadership responsibilities, and only had to be reminded of them.

I got down to basics with him: “Colonel, I am not interested in stirring up a bucket of manure. When one is through, he still has a bucket of manure. I’ll tell you exactly what I want, because I can’t lead a platoon of men into combat who are mentally and physically sick. And, as far as I am concerned, this whole division is sick.”

A meeting was held again. The Colonel did apologize to the group. The numb brained Captain, probably in fear of his own future in the National Guard, placed his hands on the Colonel’s shoulder as he started to get up and stood at the podium instead. He offered his apologies for his actions and that ended this problem—at least the part played by the division leadership. I didn’t make any friends that day, nor could I ever expect a promotion. Nevertheless, I did get the respect of my own men, which I needed. The story soon spread from the company clerk who forwarded my letter.

Christians and Jews

The next day I was asked by my company commander if I would make an attempt to fix the company’s venereal problem. Only one of my men contacted the disease, and the only difference was a little leadership that stood against the accepted norms of the day.

It took a little preparation for the company training session I had in mind to reduce the venereal rate in the company. I went to the army hospital and got some bacteria plates with live bacteria growing on them. I also got some rubber condoms the men were supposed to use as a prophylactic (something intended to prevent disease), a bag of sugar, and a blackboard.

When the men were all seated in front of me, I started out by asking a few questions: “How many of you men claim to be either a Christian or a Jew? As I looked out over the group, almost every hand went up. I went on: “Interesting, isn’t it? There’s probably not one among you who really believes the Bible where it talks about the law of chastity, or its prohibition of adultery.”

I let them think about it before I asked another question, which they probably had not considered: “How many of you are considering marriage when you get home? And for those of you who are married, how many of you have considered the possibility of infecting your wife with one of the most disabling disease’s on this earth?”

Valuable Object Lesson

I didn’t wait for an answer, nor did I expect one. I proceeded to take out a bacteria plate from my paper bag. I continued quite authoritatively: “Let me demonstrate what bacteria are fellows. This small colony I am scooping up from the surface of this plate contains millions of bacteria. Each one has the potential of causing a disease. The reason you can’t see them is the same reason you can’t see a grain of sugar if I throw this handful of sugar on the floor.” As I threw the sugar on the floor, I took out the condom.

I asked several men to come down and form a semi-circle in front of me, so I could put on a little demonstration. Several interested men came forward.

“See this small scoop of bacteria I took from this bacteria plate?” I didn’t wait for an answer. “You can see it because there are millions of the bacteria in one colony. Now, see if you can see any of them if I dilute them in this condom full of water?” I then took the colony of bacteria that was on the end of the wire loop I had made, and stirred the water with it.

“Look!” I said. All of the men gathered a little closer to look inside of the condom.

At that moment I deliberately dropped the condom so the water splashed on the men. Some almost became hysterical, as they jumped backward and attempted to wipe the water off themselves.

I calmed them by telling them I had deliberately led them to believe that the bacteria were gonorrhea bacteria, but in fact they were harmless micro-coccus bacteria.

Then I hit the blackboard with a stick to make a cracking noise to get their attention.

“Isn’t that interesting?” I fairly bellowed out to them.

“You guys will literally spend the night with a diseased prostitute, and think nothing of it. When you are sober as you are now, you become frightened with just the thought that I might have splashed some disease causing bacteria on your clothes.”

New Rules

“From now on, there are going to be some new rules around here, and they are going to be enforced!” I said this in as firm a voice as I could, to make sure they understood that I meant business.

“No GI will leave this post alone.” Each squad had two non-commissioned officers—a corporal and a sergeant. “If you leave the post you will go in groups of half a squad. Each half squad will be accompanied by a noncom. Each group will at all times have one man in that group who will not drink, and will remain sober the entire night. It will be his responsibility to make sure the rest of you do not visit a whore house. All whore houses are from this hour off limits. If any noncommissioned officer in this company violates this ruling, he will be busted to a buck private.

Are there any questions?” I didn’t wait for a response. “Dismissed!” I ordered, and then left the men to reflect on what they had just witnessed and heard.

Religious Principles

This action should have been taken from the beginning of the 40th’s stay in Japan. I could not believe that an army about to go into combat would have to resort to Sodom and Gomorrah tactics to build moral, and to prepare men for combat. I could not believe that the people of the United States were losing what had made this country great—a sense of pride in and loyalty to a nation founded on moral and religious principles.

Preparing for War

After this teaching exercise the division started to get serious about its preparation for Korea. I kept my men so busy, they had little time to get in trouble. I had a two and one-half ton truck back up to the ammunition dump. We fired all the ammunition we could load, just to get the men used to battle noises and to the effects of their weapons.

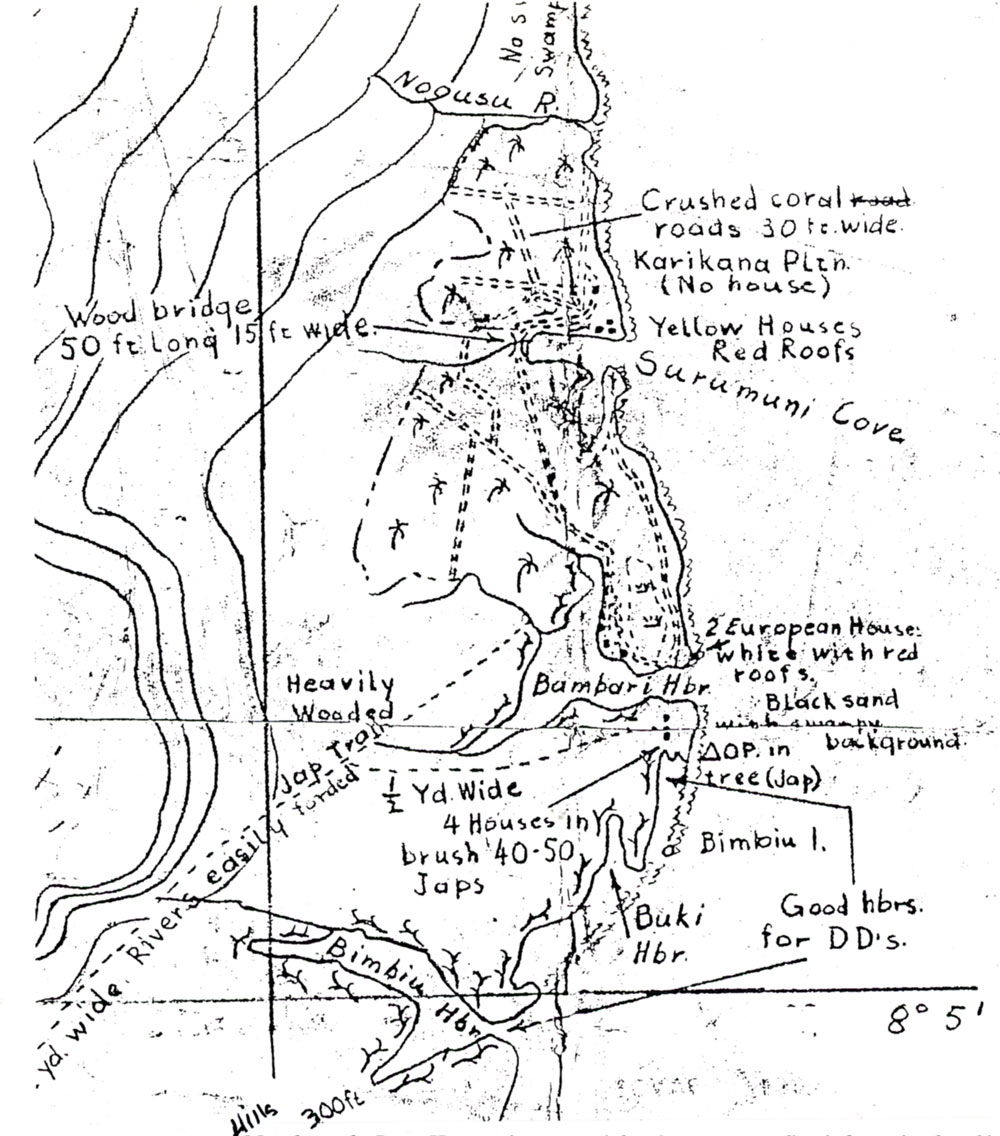

On other days, my platoon traveled throughout Japan, mapping bridges and making planned preparations to blow up those bridges if the need ever arose. If the war spread, there was still a possibility that the Chinese with Russia’s help could invade Japan.

Finding Time to Relax

Japan, 1951. Back (left to right): Thompson, ?, Elvey Farley, Eugenio Chavez; Front (left to right): Dan Noorlander, Bob Warden.

When we were away from camp in some remote area of northern Japan, we also played and rested at night. We would visit the local Japanese police stations and exchange views, talking about World War II. We showed them our weapons, and the police showed us the mug books of local prostitutes who were licensed to practice their profession. It was not hard to pick them out on the streets. They broke away from Japanese tradition and wore high heels and silk stockings.

Sometimes we would visit a Japanese cabaret when our work was over. I permitted the men to relax with Japanese dress furnished to them by a local hotel, and the men danced with the small young ladies who were there. Some six foot Gls would lift up their very small partners to eye level height as they danced, to the enjoyment of everyone looking on.

A Practical Joke

The Japanese bathed in public baths furnished at most hotels. My men knew of this and arranged to bathe in one. This was before I knew what public baths were all about. As I settled down in the hot water, after washing myself from a small wooden pail, several hotel maids came in the room. They disrobed, washed themselves, and entered the large square bath with me. My face turned bright red. The water was so hot I just about cooked. Finally, the maids left so I could get out. The next morning my men asked me how I liked my bath. I responded by saying: “Now who was the wise guy that set up that situation? All I want to say is, Thank you!” The men had great fun getting me on that one.

I don’t think the men ever believed that I would accept the hotel managements offer to supply me with a bed partner that night, which was customary for commissioned officers. I knew that if I had, I would have lost their respect. If I had lost their respect, perhaps the following months would have turned out differently for me and for the men under me.

Attending Church

Just before I left for Korea, I found time to visit a local Mormon Church. I found that it was organized very much like my own ward back home in the States, except the members didn’t wear shoes, and I couldn’t understand a word they were saying. Most of the members were women and young ladies. The men were a little slower at responding to this new religion.

Final Thoughts

I often reflect on the time I spent in Japan, the beautiful culture and the warm hospitality I received from the people wherever I traveled. I thought of the wounded Japanese soldier who I gave water and chocolate to in the Metanikau River Pocket, and wondered if I would ever see him again.

I thought of the many men I had killed, and began to question my own loyalty to a system of government that seemed to forget about morality and national pride. I do love the United States, but worry about its future. I began to wonder if all our wars had moral implications, and if perhaps there was a better answer than what comes out of a cannon barrel.

Japanese farmers during World War II.

I found some of the answers in Guatemala when my wife and I served as agriculture missionaries for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints many years after the war (1973-1974). Korea, however, is where I was exposed to the same army leadership problems that I had encountered during World War II. Only this time it was getting to me.