Lieutenant Dan Noorlander

March 12, 1921 — October 3, 1990

Korean War

In his account of Japan and Korea, Lt. Noorlander describes some of the same problems with army leadership during the Korean War that he encountered in Hawaii during World War II. He also describes what can happen when leaders stand up against evil, and establish a moral pattern that men can follow.

Right: Lt. Noorlander in Japan with Mount Fuji in the background. Picture taken December 20, 1951 at Camp Fuji McNair.

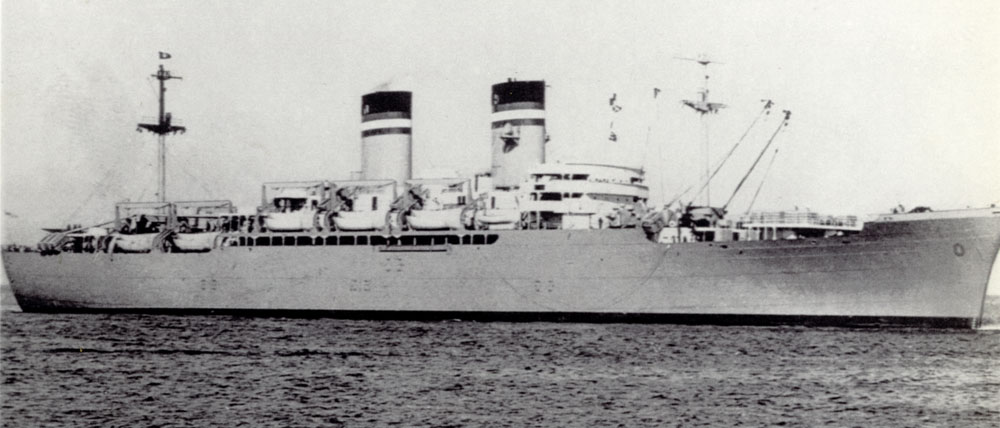

The USS General M. C. Meigs transported Lt. Noorlander to Japan for training before going to Korea.

Dorothy received this picture from Sgt. Monte Rubin, June 22, 2002.

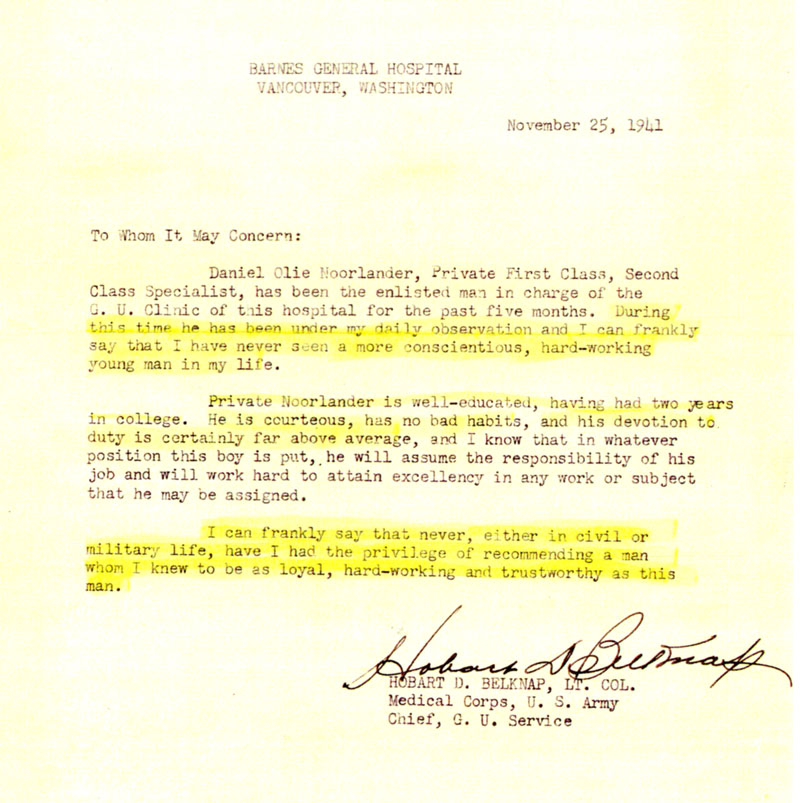

Before Enlisting

I went to work for General Mills after I graduated from College. It gave me experience, but it wasn’t what I wanted to do with my life. We moved to Oregon where we purchased a dairy farm and logging operation with my family. Even though Dorothy and I shared the down payment with my father and brother from accumulated army pay, it didn’t turn out to be a partnership farm operation. We didn’t earn an income on the ranch because everything went to pay off the mortgage.

Dorothy in Oregon, eight months pregnant.

The war in Korea was going on, so I enlisted as a way to support my family. When my orders arrived, I was happy to leave this lonely spot in the woods where the only access to the city was by boat. Dorothy was pregnant and wanted to go back to California to have the baby, so it was a good time to make the change. Being a soldier was something I knew about, and the way I could serve both my family and my country. I was away for the next fourteen months.

Military Service

I was first sent to Camp Roberts to train troops. It only took about two weeks before I decided that rear area army life was not for me. I asked for a transfer to Korea. My transfer was accepted.

I ended up in Japan with the 40th Infantry Division, assigned to the 223rd Infantry Intelligence and Reconnaissance platoon. This was the only combat platoon of the headquarters company.

Lt. Noorlander: “After a hard days work. Me sitting on bumper of the jeep. Ojoji Hani area in Japan. I & R Platoon. August 1951. Getting ready for Korea.”

We spent the following months training near Sendai, Japan, in preparation for the war in Korea. I discovered that the leadership of the 40th Infantry Division had about the same mentality as the leadership of the 161st Infantry Division in the Solomon Islands (World War II). Combat and experience turned things around a bit.

A Moral Problem

Most of the company commanders wanted to appear to be good guys to their troops. They decided that providing company parties was the best way to boost the men’s moral. The parties consisted of an issue of Japanese beer supplied in barrels to the company mess halls. They also provided their own version of a USO show by hiring prostitutes to perform strip shows for the men. After the men’s brains were stimulated and numbed sufficiently, they were allowed to visit the whore houses in Sendai. The by-products of this stupidity soon manifested itself in a division wide venereal rate of over 80 percent. If it were not for the newly discovered penicillin, the consequence to the division would have been disastrous. I only remember too well the suffering and mental problems of those GIs at Barnes General Hospital when I was an enlisted man during World War II.

From the division commander on down, the behavior of the commissioned officers suggested a court martial for almost all of them. The General, probably at the taxpayer’s expense, imported his girl friend from the states. All the hired help, including the cooks, were Japanese prostitutes that lived openly in the barracks with the GIs. Often a soldier had to step over them before he could get to his own bed.

Company officer’s bragged about their exploits in local brothels. The next day they were so exhausted, they were incapable of carrying out their responsibilities. Every morning at sick call there were hundreds of GIs waiting in line for a penicillin shot. Unfortunately, a small percentage would never be cured. Even penicillin could not take care of all the infections spread by sexual contact.

Standing Against Evil

We had division meetings concerning the articles of war that had to be taught to the men from time to time. At one such meeting of commissioned and non-commissioned officers, the meeting turned out to be a recitation of pornographic jokes by the teacher, a division Captain.

I and Chaplain Nelson, a friend of mine, walked out of the meeting. I went to company headquarters and looked up the article of war concerning this type of activity. I turned in my resignation as a commissioned officer, with the explanation that I felt I could no longer prepare the men under my command, nor could I lead them into combat with the mental and physical handicaps imposed upon them by the leadership of that division. At the bottom of the page I gave notice that a copy of my resignation would be sent to my congressman. I sent it through channels.

The response was fast. The Colonel who was in charge of the meeting offered me his apologies. He asked me if I would change my mind, if he offered the whole division an apology. Apparently he had second thoughts about his leadership responsibilities, and only had to be reminded of them.

I got down to basics with him: “Colonel, I am not interested in stirring up a bucket of manure. When one is through, he still has a bucket of manure. I’ll tell you exactly what I want, because I can’t lead a platoon of men into combat who are mentally and physically sick. And, as far as I am concerned, this whole division is sick.”

A meeting was held again. The Colonel did apologize to the group. The numb brained Captain, probably in fear of his own future in the National Guard, placed his hands on the Colonel’s shoulder as he started to get up and stood at the podium instead. He offered his apologies for his actions and that ended this problem—at least the part played by the division leadership. I didn’t make any friends that day, nor could I ever expect a promotion. Nevertheless, I did get the respect of my own men, which I needed. The story soon spread from the company clerk who forwarded my letter.

Christians and Jews

The next day I was asked by my company commander if I would make an attempt to fix the company’s venereal problem. Only one of my men contacted the disease, and the only difference was a little leadership that stood against the accepted norms of the day.

It took a little preparation for the company training session I had in mind to reduce the venereal rate in the company. I went to the army hospital and got some bacteria plates with live bacteria growing on them. I also got some rubber condoms the men were supposed to use as a prophylactic (something intended to prevent disease), a bag of sugar, and a blackboard.

When the men were all seated in front of me, I started out by asking a few questions: “How many of you men claim to be either a Christian or a Jew? As I looked out over the group, almost every hand went up. I went on: “Interesting, isn’t it? There’s probably not one among you who really believes the Bible where it talks about the law of chastity, or its prohibition of adultery.”

I let them think about it before I asked another question, which they probably had not considered: “How many of you are considering marriage when you get home? And for those of you who are married, how many of you have considered the possibility of infecting your wife with one of the most disabling disease’s on this earth?”

Valuable Object Lesson

I didn’t wait for an answer, nor did I expect one. I proceeded to take out a bacteria plate from my paper bag. I continued quite authoritatively: “Let me demonstrate what bacteria are fellows. This small colony I am scooping up from the surface of this plate contains millions of bacteria. Each one has the potential of causing a disease. The reason you can’t see them is the same reason you can’t see a grain of sugar if I throw this handful of sugar on the floor.” As I threw the sugar on the floor, I took out the condom.

I asked several men to come down and form a semi-circle in front of me, so I could put on a little demonstration. Several interested men came forward.

“See this small scoop of bacteria I took from this bacteria plate?” I didn’t wait for an answer. “You can see it because there are millions of the bacteria in one colony. Now, see if you can see any of them if I dilute them in this condom full of water?” I then took the colony of bacteria that was on the end of the wire loop I had made, and stirred the water with it.

“Look!” I said. All of the men gathered a little closer to look inside of the condom.

At that moment I deliberately dropped the condom so the water splashed on the men. Some almost became hysterical, as they jumped backward and attempted to wipe the water off themselves.

I calmed them by telling them I had deliberately led them to believe that the bacteria were gonorrhea bacteria, but in fact they were harmless micro-coccus bacteria.

Then I hit the blackboard with a stick to make a cracking noise to get their attention.

“Isn’t that interesting?” I fairly bellowed out to them.

“You guys will literally spend the night with a diseased prostitute, and think nothing of it. When you are sober as you are now, you become frightened with just the thought that I might have splashed some disease causing bacteria on your clothes.”

New Rules

“From now on, there are going to be some new rules around here, and they are going to be enforced!” I said this in as firm a voice as I could, to make sure they understood that I meant business.

“No GI will leave this post alone.” Each squad had two non-commissioned officers—a corporal and a sergeant. “If you leave the post you will go in groups of half a squad. Each half squad will be accompanied by a noncom. Each group will at all times have one man in that group who will not drink, and will remain sober the entire night. It will be his responsibility to make sure the rest of you do not visit a whore house. All whore houses are from this hour off limits. If any noncommissioned officer in this company violates this ruling, he will be busted to a buck private.

Are there any questions?” I didn’t wait for a response. “Dismissed!” I ordered, and then left the men to reflect on what they had just witnessed and heard.

Religious Principles

This action should have been taken from the beginning of the 40th’s stay in Japan. I could not believe that an army about to go into combat would have to resort to Sodom and Gomorrah tactics to build moral, and to prepare men for combat. I could not believe that the people of the United States were losing what had made this country great—a sense of pride in and loyalty to a nation founded on moral and religious principles.

Preparing for War

After this teaching exercise the division started to get serious about its preparation for Korea. I kept my men so busy, they had little time to get in trouble. I had a two and one-half ton truck back up to the ammunition dump. We fired all the ammunition we could load, just to get the men used to battle noises and to the effects of their weapons.

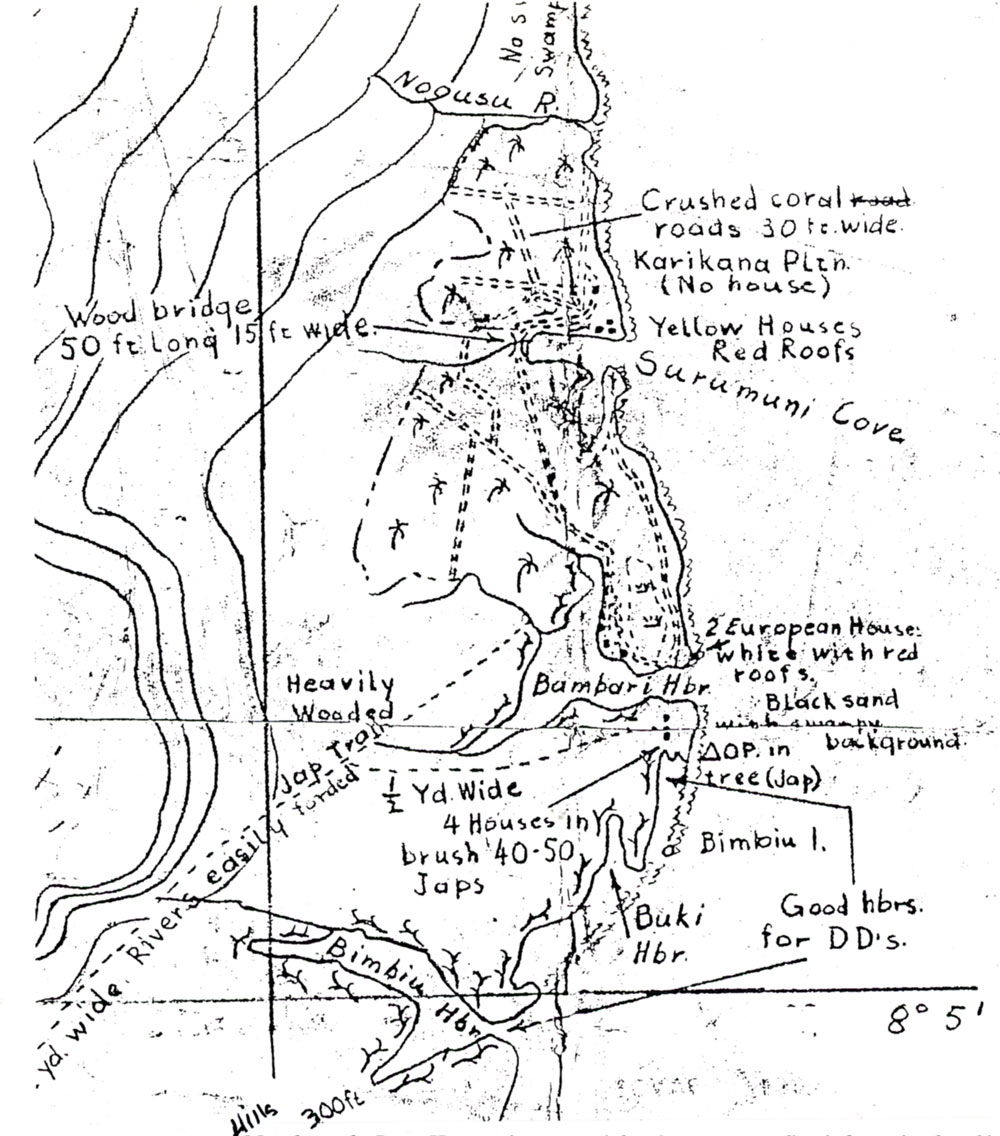

On other days, my platoon traveled throughout Japan, mapping bridges and making planned preparations to blow up those bridges if the need ever arose. If the war spread, there was still a possibility that the Chinese with Russia’s help could invade Japan.

Finding Time to Relax

Japan, 1951. Back (left to right): Thompson, ?, Elvey Farley, Eugenio Chavez; Front (left to right): Dan Noorlander, Bob Warden.

When we were away from camp in some remote area of northern Japan, we also played and rested at night. We would visit the local Japanese police stations and exchange views, talking about World War II. We showed them our weapons, and the police showed us the mug books of local prostitutes who were licensed to practice their profession. It was not hard to pick them out on the streets. They broke away from Japanese tradition and wore high heels and silk stockings.

Sometimes we would visit a Japanese cabaret when our work was over. I permitted the men to relax with Japanese dress furnished to them by a local hotel, and the men danced with the small young ladies who were there. Some six foot Gls would lift up their very small partners to eye level height as they danced, to the enjoyment of everyone looking on.

A Practical Joke

The Japanese bathed in public baths furnished at most hotels. My men knew of this and arranged to bathe in one. This was before I knew what public baths were all about. As I settled down in the hot water, after washing myself from a small wooden pail, several hotel maids came in the room. They disrobed, washed themselves, and entered the large square bath with me. My face turned bright red. The water was so hot I just about cooked. Finally, the maids left so I could get out. The next morning my men asked me how I liked my bath. I responded by saying: “Now who was the wise guy that set up that situation? All I want to say is, Thank you!” The men had great fun getting me on that one.

I don’t think the men ever believed that I would accept the hotel managements offer to supply me with a bed partner that night, which was customary for commissioned officers. I knew that if I had, I would have lost their respect. If I had lost their respect, perhaps the following months would have turned out differently for me and for the men under me.

Attending Church

Just before I left for Korea, I found time to visit a local Mormon Church. I found that it was organized very much like my own ward back home in the States, except the members didn’t wear shoes, and I couldn’t understand a word they were saying. Most of the members were women and young ladies. The men were a little slower at responding to this new religion.

Final Thoughts

I often reflect on the time I spent in Japan, the beautiful culture and the warm hospitality I received from the people wherever I traveled. I thought of the wounded Japanese soldier who I gave water and chocolate to in the Metanikau River Pocket, and wondered if I would ever see him again.

I thought of the many men I had killed, and began to question my own loyalty to a system of government that seemed to forget about morality and national pride. I do love the United States, but worry about its future. I began to wonder if all our wars had moral implications, and if perhaps there was a better answer than what comes out of a cannon barrel.

Japanese farmers during World War II.

I found some of the answers in Guatemala when my wife and I served as agriculture missionaries for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints many years after the war (1973-1974). Korea, however, is where I was exposed to the same army leadership problems that I had encountered during World War II. Only this time it was getting to me.

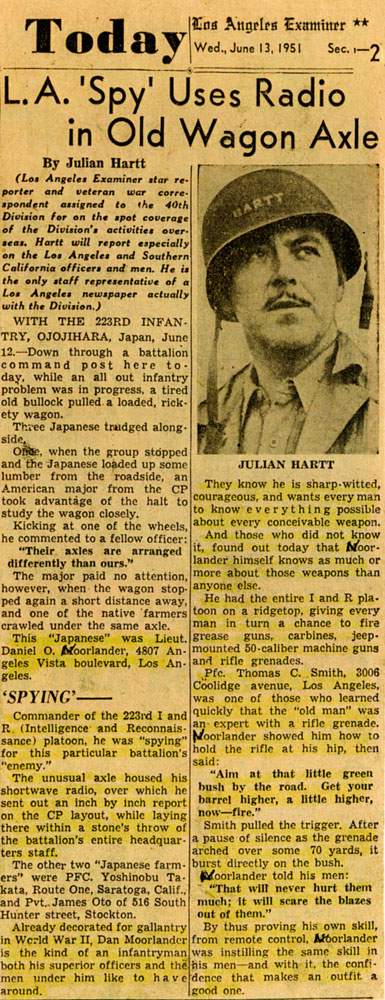

Reporters played an important role during the Korean War, often telling stories that otherwise would be forgotten.

Lt. Noorlander referred to training exercises like those described on this page, but provided few if any details.

He focused on matters that concerned him the most, including issues that affected the well-being of the men who served with him. That concern was reflected in how he prepared them for war.

L.A. 'Spy' Uses Radio in Old Wagon Axle

By Julian Hartt

(Los Angeles Examiner star reporter and veteran war correspondent assigned to the 40th Division for on the spot coverage of the Division’s activities overseas. Hartt will report especially on the Los Angeles and Southern California officers and men. He is the only staff representative of a Los Angeles newspaper actually with the Division.)

WITH THE 223RD INFANTRY, OJOJIHARA, Japan, June 12.—Down through a battalion command post here today, while an all out infantry problem was in progress, a tired old bullock pulled a loaded, rickety wagon.

Three Japanese trudged alongside.

Once, when the group stopped and the Japanese loaded up some lumber from the roadside, an American major from the CP took advantage of the halt to study the wagon closely.

Kicking at one of the wheels, he commented to a fellow officer:

“Their axles are arranged differently than ours.”

The major paid no attention, however, when the wagon stopped again a short distance away, and one of the native farmers crawled under the same axle.

This “Japanese” was Lieut. Daniel O. Noorlander, 4807 Angeles Vista boulevard, Los Angeles.

‘SPYING’—

Commander of the 223rd I and R (Intelligence and Reconnaissance) platoon, he was “spying” for this particular battalion’s “enemy.”

The unusual axle housed his shortwave radio, over which he sent out an inch by inch report on the CP layout, while laying there within a stone’s throw of the battalion’s entire headquarters staff.

The other two “Japanese farmers” were PFC. Yoshinobu Takata, Route One, Saratoga, Calif., and Pvt. James Oto of 516 South Hunger street, Stockton.

Already decorated for gallantry in World War II, Dan Noorlander is the kind of an infantryman both his superior officers and the men under him like to have around.

They know he is sharp-witted, courageous, and wants every man to know everything possible about every conceivable weapon.

And those who did not know it, found out today that Noorlander himself knows as much or more about those weapons than anyone else.

He had the entire I and R platoon on a ridge top, giving every man in turn a chance to fire grease guns, carbines, jeep-mounted 50-caliber machine guns and rifle grenades.

Pfc. Thomas C. Smith, 3006 Coolidge Avenue, Los Angeles, was one of those who learned quickly that the “old man” was an expert with a rifle grenade. Noorlander showed him how to hold the rifle at his hip, then said:

“Aim at that little green bush by the road. Get your barrel higher, a little higher, now—fire.”

Smith pulled the trigger. After a pause of silence as the grenade arched over some 70 yards, it burst directly on the bush.

Noorlander told his men:

“That will never hurt them much; it will scare the blazes out of them.”

By thus proving his own skill, from remote control, Noorlander was instilling the same skill in his men—and with it, the confidence that makes an outfit a good one.

That’s my boy!!!

223rd ‘Highlanders’ Shield Wanted Man

SCHIM–First Lt. Daniel Noorlander has a price on his head.

The 223rd Infantry claims there is a standing offer of a five-day pass to any man who can capture Noorlander, head of the 223rd’s crack I&R Platoon.

The 36 men of the platoon, who call themselves “Noorlander’s Highlanders,” usually act as aggressors in BCT tests and claim they’re more at home behind enemy lines than in front of them.

With a complete background of US infantry tactics, the Highlanders have weeks of training with weapons of the Chinese army.

“On their own time,” said the platoon sergeant, SFC David Hand, “the men have taken a course in Russian weapons and can field-strip many Red Army pieces.”

A typical Highlander exploit occurred during the last 223rd RCT problem. Noorlander and two of his men, disguised as Japanese farmers, rode through the lines on a wagon loades with hay. They had only one close call. A major thought the 300-pound radio they had strapped to the wagon was a new type of axle.

“I wonder what he would have thought,” grinned Hand, “if he found the grenades and rifles we had stashed under the hay.”

Another platoon job is the almost endless one of road reconnaissance. Up to now, they’ve recorded more than 2500 miles on Honshu, from broad highways to one-horse trails. [Lt. Noorlander: 4000 miles.]

Major Bud Taylor wrote, “Lt. Noorlander always added something to an assignment, making it successful beyond anyone’s expectations. The information he gained was often enhanced by the devices he would invent.”

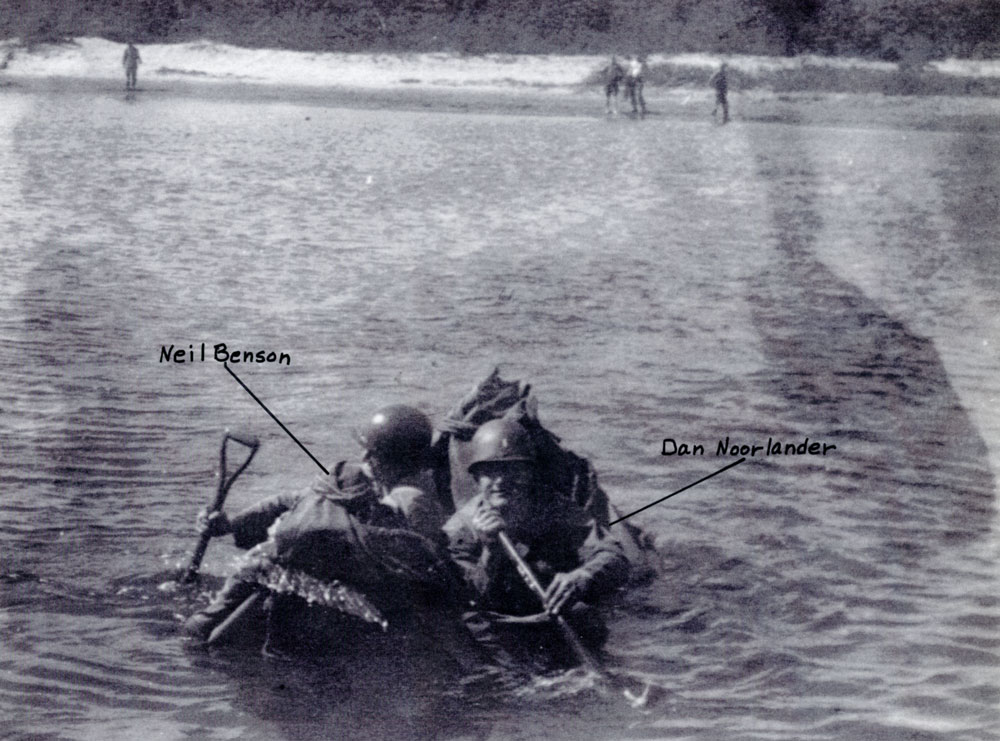

Left: Neil Benson and Lt. Noorlander testing a boat made out of shelter halves.

Leaving Japan for Korea

The 40th Division left Tokyo harbor and passed southward around the southern end of the Japanese Islands. We could see the smoke from one of her active volcanoes as we then headed northward to Korea.

When we arrived, we were loaded aboard two and half ton trucks and hauled northward toward the 38th Parallel. Our first night was spent sleeping in mummy bags in foot deep snow. Later we were provided with tents that covered 4 foot deep dug out living quarters heated with oil stoves.

Enemy action was stabilized roughly along the 38th Parallel where both sides probed each other’s lines with patrol activity. Most of our fighting, however, was confined to artillery and Air Force bombings against Chinese positions, and a propaganda war of words over loud speakers, and dropping leaflets over their positions by our small cub planes.

Chinese position overlooking Kumsong at 38th parallel, with puffs of artillery smoke.

I was on such a propaganda mission flying over Chinese lines when the pilot throttled down the motor to lose altitude. The Chinese opened up with their anti-aircraft weapons. The tracer bullets appeared to float upward at us in a long arc that came too close for comfort. I tapped the pilot on the shoulder and told him to pull up.

When we landed, we were told that they thought we had been shot down. What really happened was another plane similar to ours was shot down in the next sector. I understand the pilot was the son of another division’s General.

Since I volunteered for this job, I was grounded and told not to go on any more missions like this. While up there, however, I was able to pick out the Chinese positions with my binoculars. Most of them were covered up and camouflaged.

Chinese Infiltrators

It was not uncommon for Chinese infiltrators to penetrate our lines and go to the rear areas and machine gun our troops as they slept in their tents. I was assigned to provide security for our regimental headquarters against this type of attack. To assist us we were provided with two trained dogs with their handlers.

One night, the headquarter company and regimental staff were watching a movie in a large tent, when one of the dog handlers asked me to follow him. When we were on the outside, he told me that his dog had sensed some enemy activity just beyond the tent area about 500 yards away.

I told one of my noncoms to round up a few men from my platoon and to bring along some rifle flares and extra clips of ammunition.

We followed the dog and his handler to the area where the dog stiffened, alerting his handler that Chinese were to our front. I told him to fall back, and that we would handle it from there.

I told my noncom to take one of the men on the right and I would take the left so that we were about a hundred yards apart. When we fired a flare, I whispered to him to flush the area with our automatic weapons while sounding like an army was charging the Chinese. Then I would give vocal commands to my imaginary army, and with my men, flush the area to our front.

As the first flare arched over the area and floated down attached to a small parachute, I started yelling orders to attack and all of us opened up. It sounded like a major war was in progress, but my ploy worked.

The dog handler came up with his dog, and I was informed that who ever was there had disappeared. The next day, I was told that three Chinese soldiers were killed by one of our infantry units about a thousand yards to our front, while trying to get back to their lines.

Our regimental commander was not experienced in war, and asked me why I had not told him the enemy was so close and why I had not informed him of my plans.

I responded with, “I didn’t have time, sir. The Chinese were on top of us and I had to make a quick decision. My job is the security of this outfit, and I did what I had to.”

Apparently, the Colonel accepted this. He did not argue or thank me. Frankly, I thought he was a little confused that a junior officer would take on this kind of responsibility.

A Publicity Stunt

I was not surprised a little later when his S3 or tactical officer visited me, and asked if I would take a patrol to the Chinese lines.

“That’s what I’m being paid for Major,” I said, “but what’s my mission?”

The week before a Captain friend of mine took his company up a draw alongside a mountainous spur known as the “boot,” which led down from the Chinese lines toward our front lines. It was just across the Kumsong River, which separated our lines.

The Chinese were waiting for them and had already zeroed in preparatory mortar fire in the draw. When the Captain took his troops up the draw, it was a classic U.S. infantry attack. Within just a few minutes the Chinese had swept the whole draw with mortar fire, and what the mortars missed, their machine guns finished. Half of the men in the company were killed including the Captain. His spine was torn up when his back pack was cut to pieces.

The Major told me that he wanted us to find out where the Chinese lines were.

The Chinese lines were well entrenched positions that pocketed the whole mountain to our front, which was penetrated by deep caves and tunnels. I was surprised that the major would think I was so gullible or so misinformed that I did not know what was going on.

Lt. Noorlander is in the passenger seat.

“Now Major,” I said, “if that’s all you want to know, I can tell you exactly where their positions are on a map. Remember, I flew over this area in a plane before I was grounded.” I had a gut feeling that I was being trapped into another one of those National Guard attacks where commanders do all their planning on a map with red and blue arrows, showing the movement of armies without any consideration for human life.

The Truth Comes Out

After a little more probing, I was finally told the real reason for the attack. The Major let his hair down a little and confessed that the commander wanted a little publicity for the folks back home. In other words, jobs back home were at stake and he needed some recognition for a promotion that would enhance his retirement fund. Few promotions are given following a war.

I thought to myself: “That horse’s petute is trading human lives for a little personal security.” I momentarily reflected on the past few months in Japan, where the General had almost incapacitated the whole division with venereal disease because of his bad example and lack of leadership. Now he wanted to establish a reputation as a combat general.

A New plan

Lt. Noorlander preparing for his next mission.

There was no justifiable military reason for the proposed attack. The Chinese and American lines were stabilized along the 38th Parallel, and the war was winding down. I quickly thought of my men, and of an alternative plan that would get us out of this dilemma.

“Look,” I said, “if you want a little publicity, this can be done, but it has to be done differently. Okay?”

He asked me what I had in mind. He was also taken back a little because I had challenged his position.

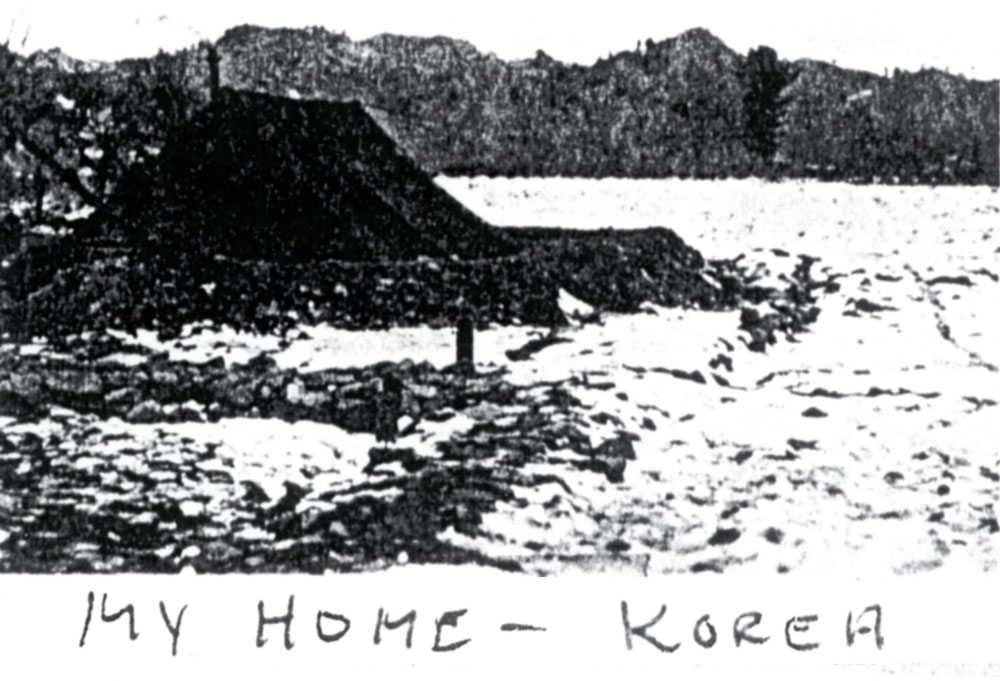

“I want a week’s preparation and all the artillery support I can get. I’ll also take your large ‘Los Angeles City Limits’ sign with me.” He agreed and I got busy. I thought to myself: “If they just want a show, I will give them one, but on my terms.”

Saving Lives

The following week every man in my platoon studied the aerial photographs of the area I had picked to reach our objective. We memorized every bomb hole and earthen ditch bank that could provide us with shelter in case we needed it. I decided to attack Chinese style with just enough flair to confuse the enemy.

Lt. Noorlander: “Last minute orders before the attack on Kumsong.”

I knew the Chinese understood American tactics, and I wanted them to believe we were going to attack American style. So, to soften up their positions, I planned a massive fire power against their lines using division artillery. I was not going to attack where the shells would land, however, as was the custom. I would attack between the two areas I had selected, one of which was the same general area where my friend’s company was almost wiped out.

Each man was camouflaged with white clothing since a full moon was projected for the night of the attack. We were not going up the draw American style, but across the 1000 yard open plain in front of the Chinese lines. The plain was laced with frozen rice paddies and snow.

Each man was provided with a five-gallon pail of timed explosives, flares, and phosphorous smoke grenades. Several men carried five-gallon pails of napalm, a jellied gasoline. Each pail was fortified with a long stick of black powder and a time fuse.

The evening before the attack we drove a half-track vehicle, which is a type of armored car, near the division outpost. We camouflaged the vehicle with brush and headed up the hill to the outpost. We planned to depart just before dark, with two minutes of twilight left so we could cross the Kumsong River. The river was not deep, but I was glad we wore insulated boots, because the temperature was dropping rapidly.

Overlooking Kumsong at 38th parallel. Lt. Noorlander is in the plane looking over enemy lines.

Heaven’s Help

Just before our departure, I was called to the outpost phone by the Major. He told me that some of our tanks had penetrated the area where we were going and that they were fired upon by machine guns. He said that we could back out if we wanted to. He apparently was having second thoughts about this mission. I was glad that at least he appeared to have a conscience.

“No Major,” I replied, “I think we can handle it.” I then led the men down the backside of the mountainous outpost to wait for the artillery barrage, which was our signal to cross the river.

Inwardly I felt a little uneasy. I said a little prayer as I led the men down the slope. I normally did not petition my Creator for any special help that was involved with the military. It was against my principles to ask for favors that our enemy had a right to. I reflected on one of my flights over the Chinese lines where I could see the puffs of artillery smoke, and remembered thinking to myself, “If I were the God of the heavens, and all these combatants were my children, who would I favor and who would I select to win the battle of that day.” I thought of the many men in the division who behaved immorally in Japan, to the point of total debasement. I thought of the Chinese and of the great moral principles taught by their teacher Confucius.

In spite of this thinking I did ask the Lord for some special help that evening. I asked that He would give me the courage to lead my men into combat that night, and that I would not reflect any fear to them. I also asked for the first time in my military career that I would be able to bring all the men home with me that night. I knew my men were not perfect, nor was I, but I did not believe I could live with myself if just one man was incapacitated or killed for this publicity stunt.

Korea, 1951-1952. Left to right: Dick Snaer, Eugenio Chavez, Paul Bousquet.

As we crouched down next to the river, waiting for the artillery, I looked at my watch. All of a sudden the audible whine of artillery shells went directly over our heads and exploded to our left and right on the Chinese positions as planned.

I motioned the men to follow me as I crossed the rather wide river. In the middle of the river I noticed my men were over cautious and this was slowing us down.

Then I had a very strange experience. It was as if I was being informed that no one was watching us—I knew that the Chinese could not or were not looking in our direction.

I stood up from my crouched position and waved my men on. They all stood up and walked across the river without any more hesitation. They followed me all the way to the edge of the Kumsong village, long before evacuated because of the war. We traveled rapidly so the Chinese wouldn’t have second thoughts about where the attack might take place.

By prearranged hand signals, I directed one squad to the left. I took a second squad to the right. Another squad stayed behind, making a corridor to our rear. This made escape possible if our flanks were attacked by the Chinese.

Again, my men hesitated. They knew that a Chinese machine gun position had been reported in that area. I had the same feeling come over me as before—I knew that no one was watching us or could see us. This may be difficult for some to believe, who have never had such an experience. I have read of similar reports on other occasions in our day. For example, when the Jews were fighting their Six Day War in Israel. Of course, the Bible is full of such stories. I am one who believes that the Lord still intervenes whenever the situation warrants it.

At that moment, as before, I stood up from a deeply crouched position. My men looked at me in disbelief. Nevertheless, both squads went about their business as planned, without hesitation or fear. We planted our explosives throughout the village. We lobbed the smoke grenades closest to us. We lobbed the flare grenades just in front of the smoke grenades, so the brilliant light would reflect against the smoke and not expose our positions. All the explosives were timed in ten minute intervals so the last ones would go off about an hour after the first ones.

Soon the napalm exploded in what appeared to be small atomic mushrooms rising from the center of grass roofed huts. Soon the whole village was on fire as explosives literally tore up the town. In all my 4th of July experiences, I have never seen such a beautiful display.

We left the village at a fast trot, just as we came in. I knew the Chinese would counter attack, or at least send a patrol to investigate this new type of warfare.

Back (from left to right): Leo Dmochowski, Ralph Holguin, Paul Bousquet, Cha(?), Coyle, Cahill; Front: Dick Iserhagen.

As promised, we didn’t leave before putting up the “Los Angeles City Limits” sign on a conspicuous post, so the whole division could see it from our lines with binoculars.

Mission Accomplished

We returned to our outpost and looked over the inferno we had started. I called for artillery on the Chinese who were by then pouring out of the hills. The artillery officer asked me over the outpost phone when we were going to quit. He assumed that he was talking to me over the sound power phone the third squad had laid down for us, in case we needed artillery support to get us out of Kumsong. “We left there twenty minutes ago,” I responded.

I could not see any artillery shells land on the Chinese, nor did the mortar fire we called for from the outpost hit its prearranged target in the center of Kumsong. I suppose the forward observers could not believe we were not still in Kumsong. I kind of believe that the Lord was protecting the other side as well. I used to listen to all the propaganda about the buck toothed Jap who sat in coconut trees resembling monkeys. I found out after the war that they were just like you and me. A few months before I talked to a Japanese soldier who lost his arm in the battle of Guadalcanal. He was a rice farmer inducted into the army to serve his war-lord masters. It appears that all nations have them.

Newspaper Report

Julian Hartt, the Los Angeles Examiner war correspondent, came the following day to interview my platoon. I gave plenty of credit to my company commander. By doing this, I was able to get every one of my men a long deserved promotion or rating and the pay that went with it.

Julian Hartt’s newspaper account. Click to enlarge.

Bronze Star

I received a Bronze Star for valor, when in reality there really wasn’t much risk taken that night. I just put into practice some lessons I learned about military tactics while serving in the Solomon Islands during World War II, and petitioned for the extra help I knew I needed, knowing I had done all I could do myself.

Regimental commander, Lt. Col. Richard F. Lynch, presents Bronze Star Medal to Lt. Noorlander during an informal ceremony near the front.

Final Reflections

When we returned with our half track the following morning after our attack, the rest of the company was eating chow. I watched my men. They were proud of themselves, as was the rest of the company. I felt good inside, because I knew I had given all I could. The success of the mission made the headlines in southern California, where many of my men came from. It told how the 40th division had wiped out a snipers town on the 38th parallel.

I also knew that the attack could have gone the other way. I had plenty of experiences on Guadalcanal and New Georgia like this one. I was thinking about this when I went to church services in a dug out room with a tent cover. The services were conducted by my friend Chaplain Nelson. I did not hear much that day because a battery of artillery was pounding away at the Chinese positions, and because my thoughts were elsewhere.

After the meeting, Chaplain Nelson told me how he and Captain Christiansen, a Colonel’s aid from the artillery division, not only made sure we got the artillery I requested, but were on their knees the entire one and a half hours we were on our mission to Kumsong, petitioning our Creator for help in my behalf. It was nice knowing I had friends like this, and all the back-up support that came with it.

A Christian Nation

It was not long after the raid on Kumsong that I was eating in the officer’s mess tent. Several officers were swapping stories about their sexual conquests and experiences in Japan.

I noticed a Korean Army officer quietly taking it all in. Later, outside of the tent, he approached me and asked me a very pointed question because something was bothering him. He asked me if it was true that America was basically a Christian nation. When I responded in the affirmative, I was not quite prepared for his observations: “You Christians really do not believe in the teachings of Christ, do you?”

Up to that moment I had not realized how much the Army’s conduct was influencing the opinions of our Allies regarding our moral character. I tried to convince him that all Americans were not made out of the same mold, and that back home the folks were, for the most part, moral people. I gave him a leather bound copy of some scriptures I had in my footlocker. He appeared very grateful for this gift and thanked me, but inside myself I had a difficult time that day. I wondered if I really told him the truth. This was, in fact, a citizen’s army, and I hoped that the conduct of some men did not reflect the moral standards of the whole nation. If it did, then we as a nation were in deep trouble.

Going Home

Soon after the attack on Kumsong, I was sent home. I had served my time in the army, and I went home to rejoin my wife and two little daughters.

After arriving home I received a letter that made all the effort worth it. It read in part:

Dear Lt. Noorlander,

Our son Bob has written, “The only good thing in the army will be gone when Lt. Noorlander goes home in a few weeks.”

Before you go, I should like to express a little of how much his father and I appreciate your guidance and influence on him and undoubtedly the rest of your boys. I have felt that you have been an answer to all of our prayers for Bob’s safety and for his wholesome attitude while in Japan and Korea. We received at least two long letters each week filled with the accomplishments and virtues of his Lieutenant.

I’m sure Bob will value your counseling and friendship all of his life, and for it we will always be grateful, too.

Sincerely,

(Mrs. Ray) Harriet Gardner

1715 East 80th Street

Seattle 5, Washington

April 3, 1952

Sgt. Monte Rubin with Lt. Noorlander. Korea 1951-1952.