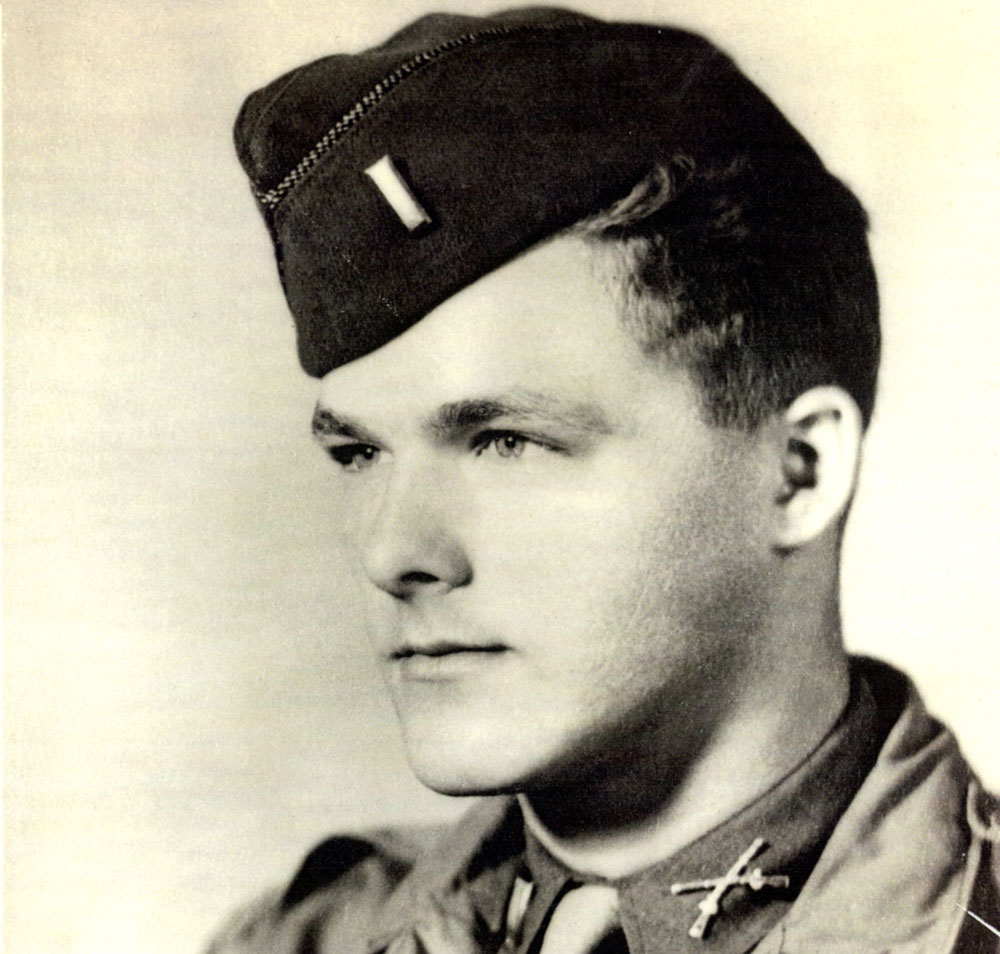

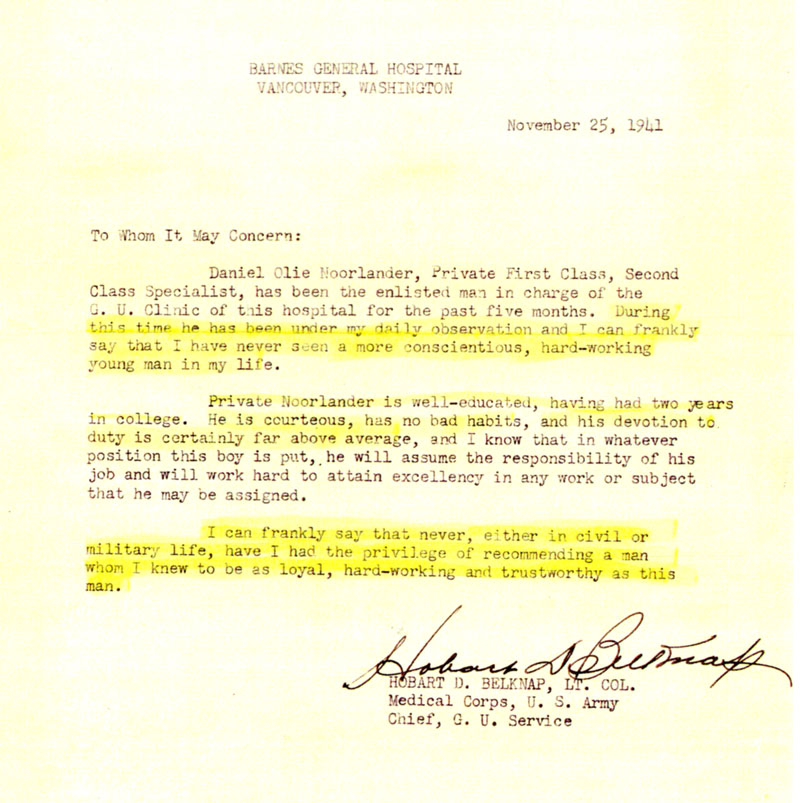

Lieutenant Dan Noorlander

March 12, 1921 — October 3, 1990

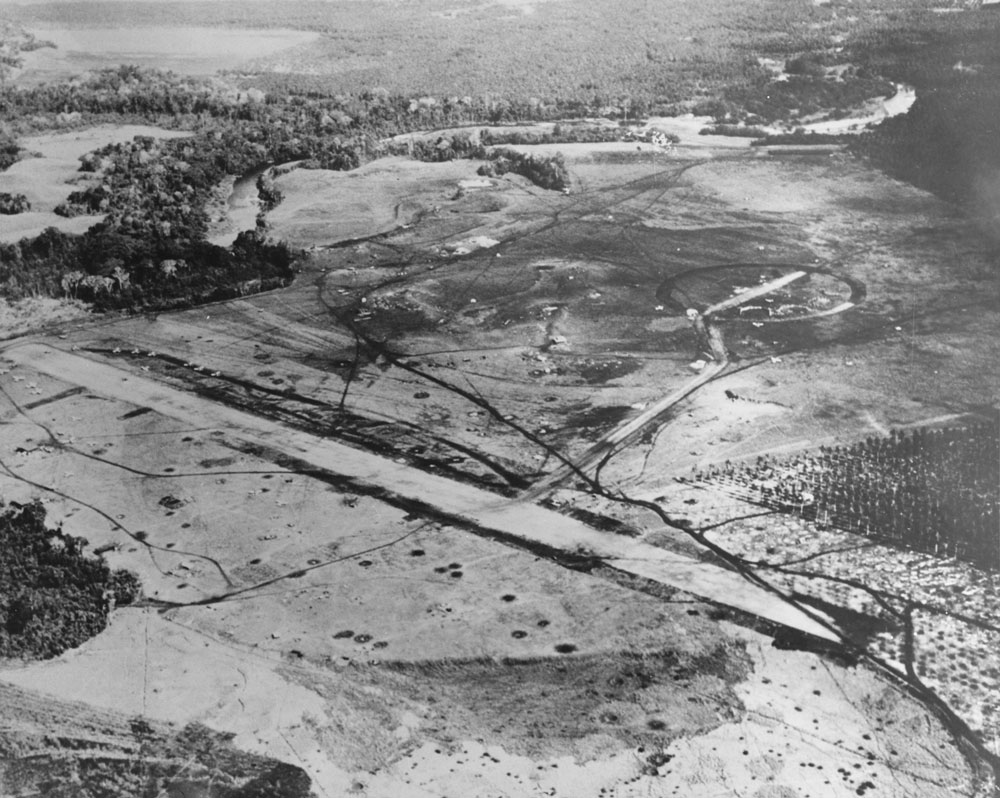

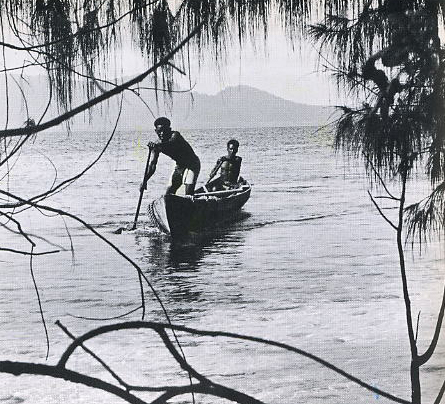

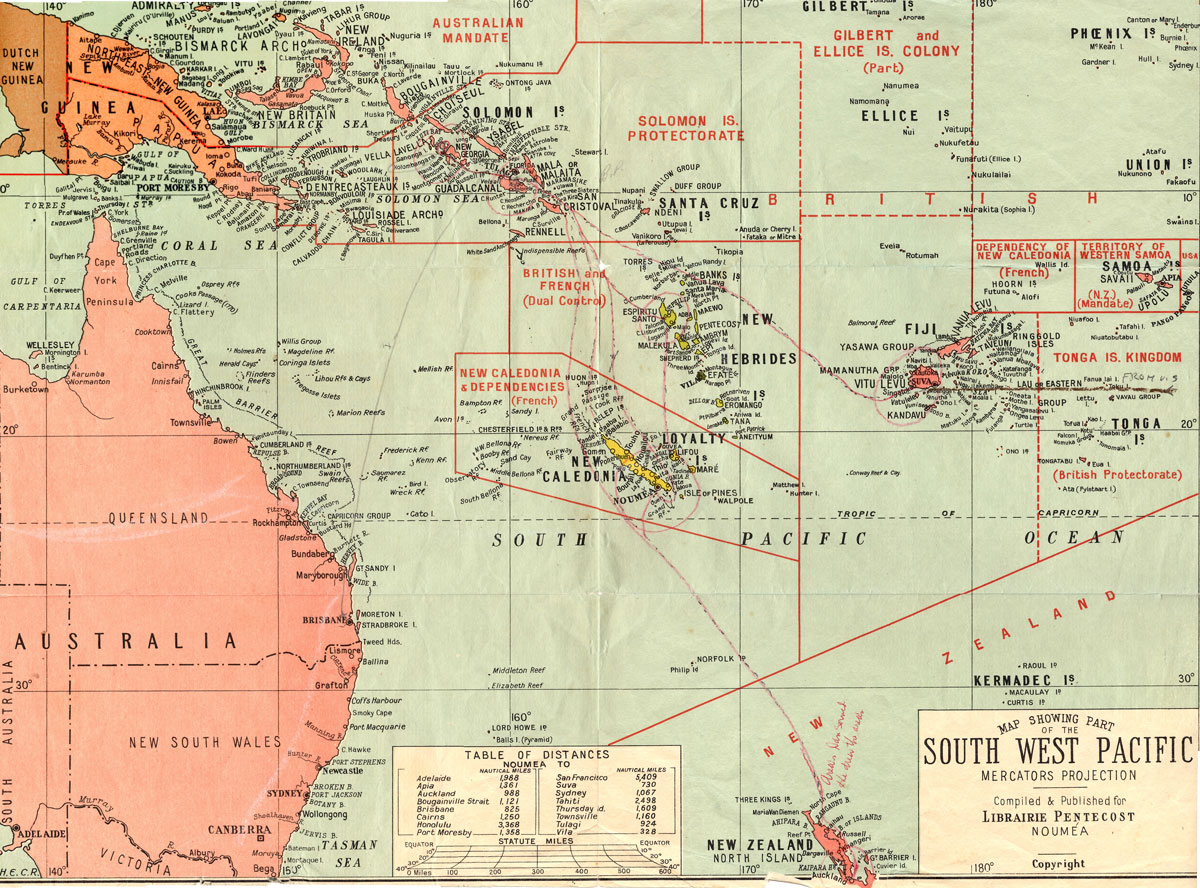

New Georgia

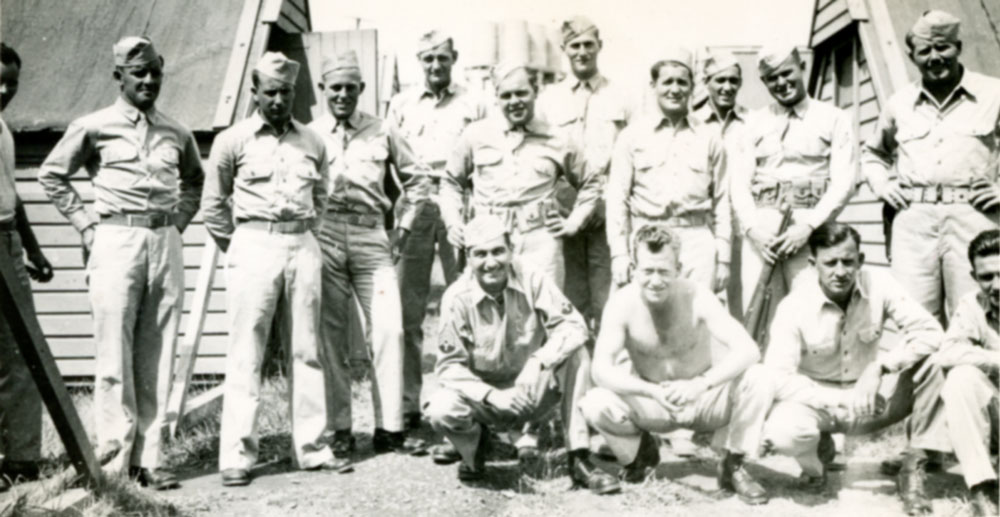

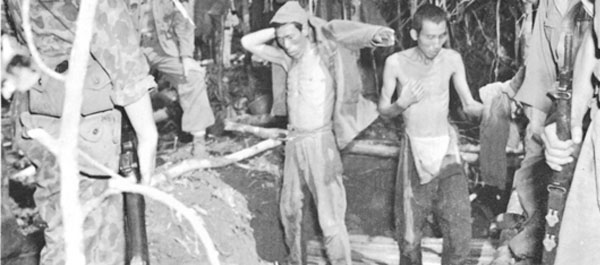

Japanese soldiers on New Georgia Island

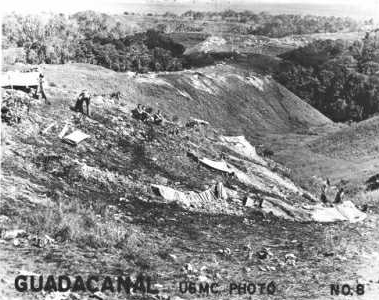

Munda Airfield – New Georgia Island

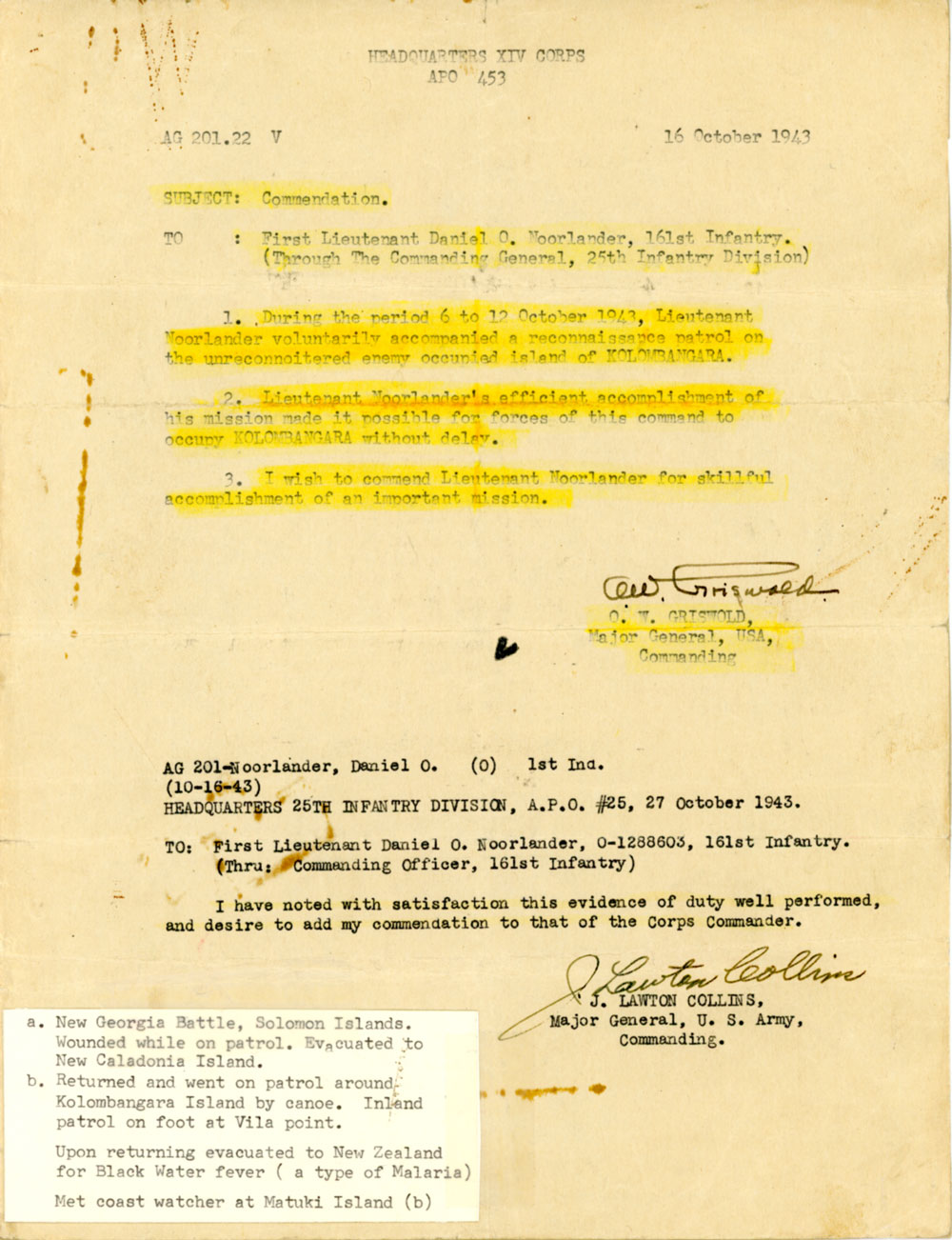

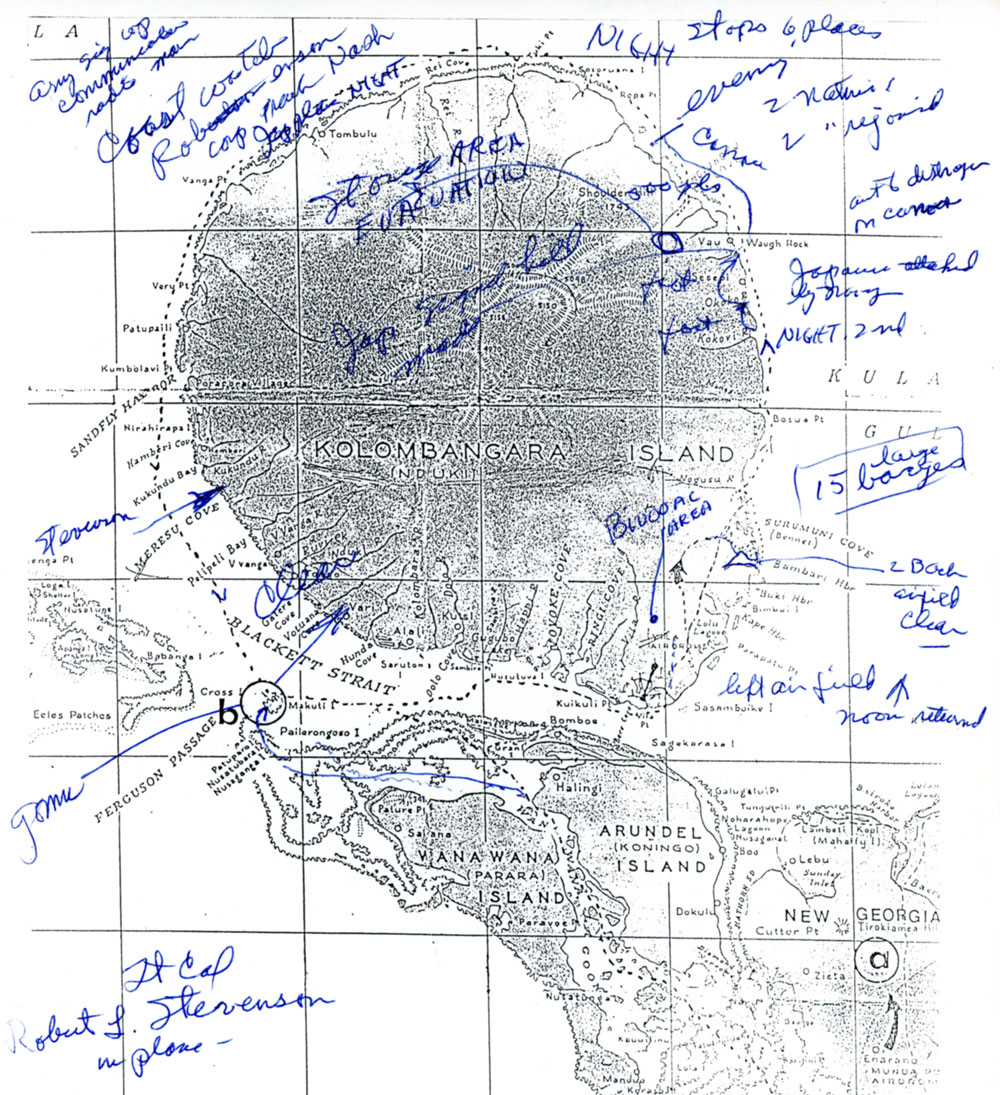

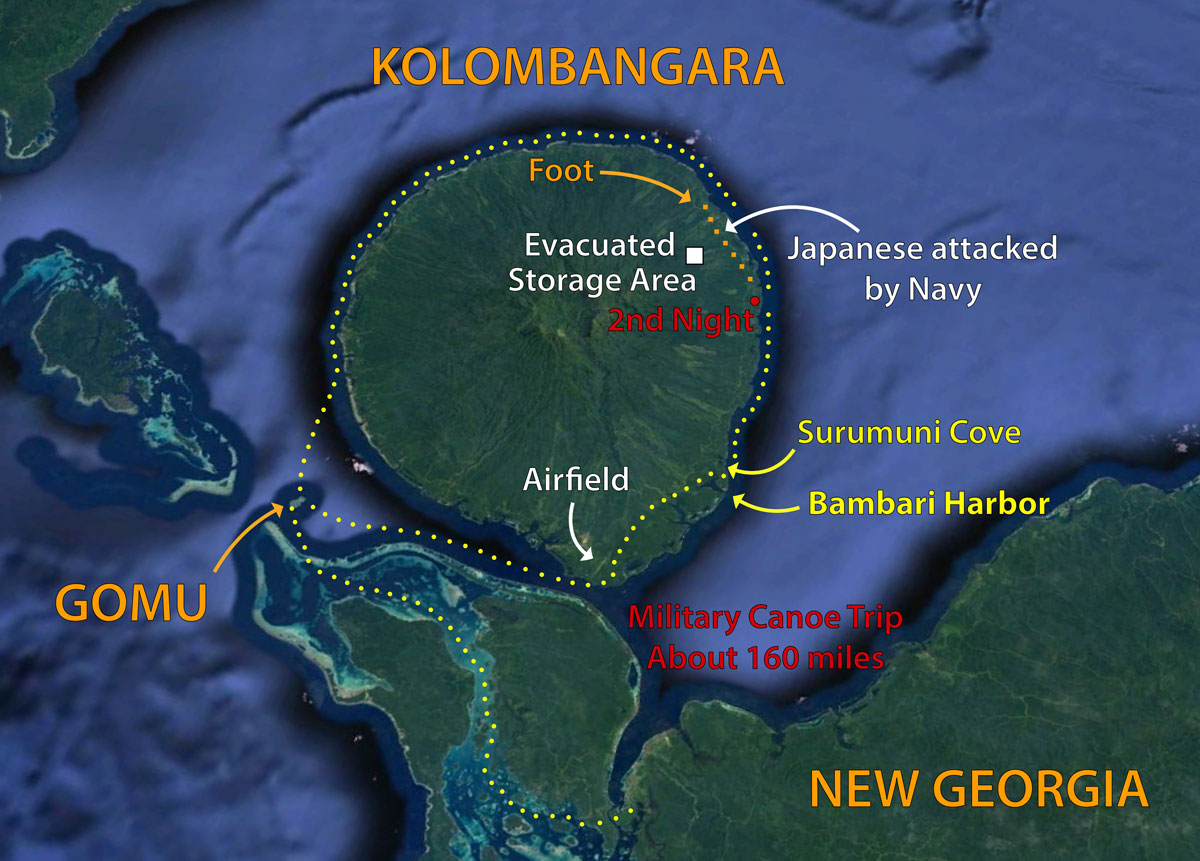

Lt. Noorlander was in the 161st Infantry Regiment, which took part in the campaign for New Georgia. His memory of the campaign matches perfectly the summaries in the next column.

Not only was Lt. Noorlander wounded in this campaign, but he received the Distinguished-Service Cross for “extraordinary heroism.”

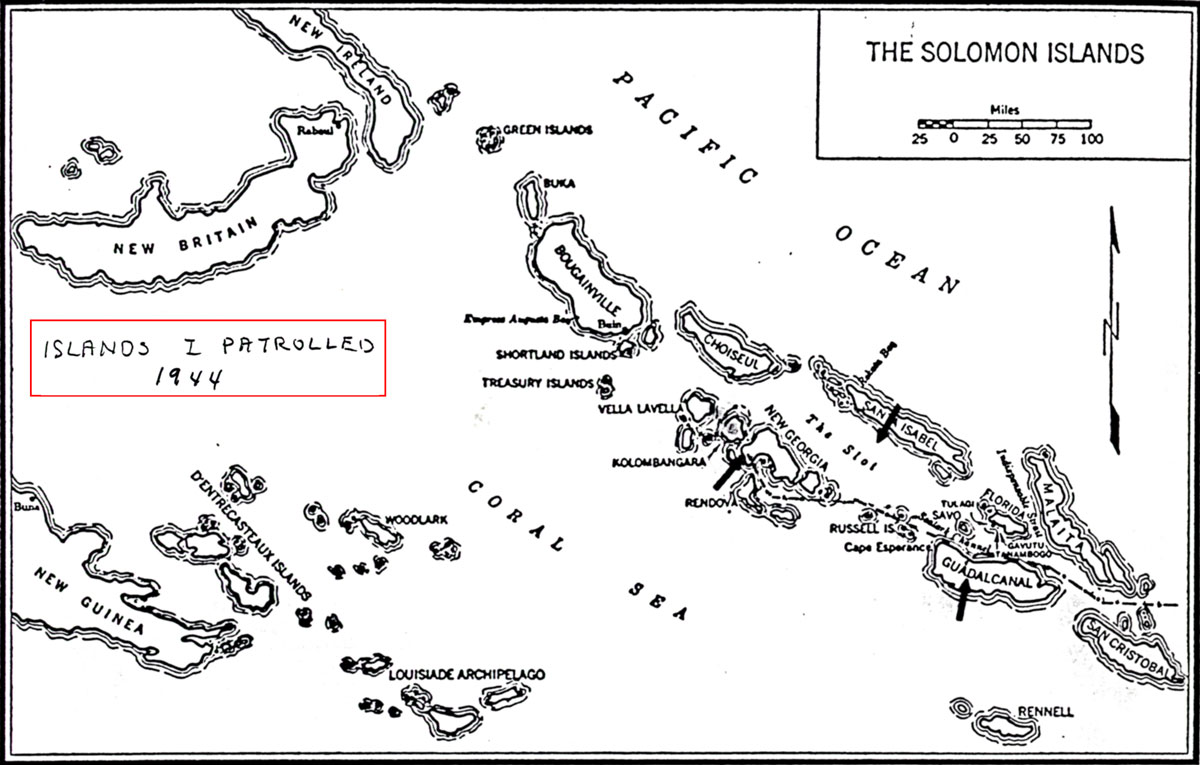

The New Georgia Campaign took place from June 20, 1943 through October 7, 1943. New Georgia is located in the central Solomon Islands. Two historical summaries are presented below. You find out in the second one that Lt. Noorlander’s Division earned the title Tropic Lightning Division for its work on Guadalcanal.

New Georgia Campaign

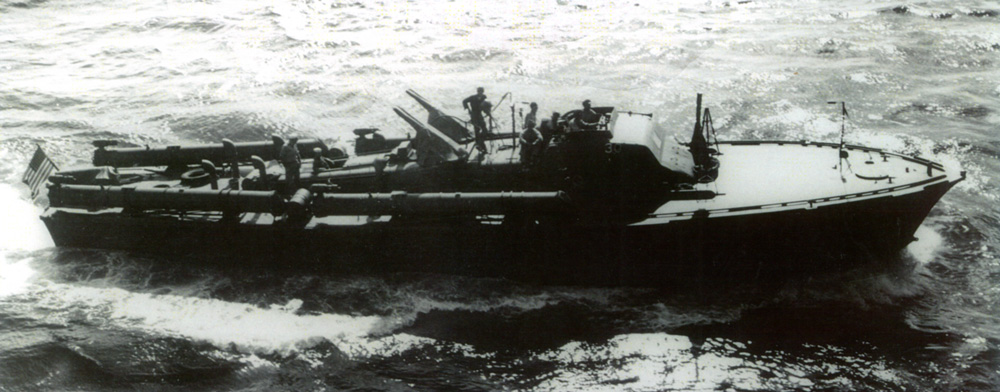

“The Allied base at Guadalcanal continued to suffer from Japanese bombing raids even after the island was declared secured on 9 February 1943. The Japanese airfield at Munda made these raids easier by giving Japanese planes a convenient place to refuel on the way to and from their main base at Rabaul. The Allies attempted to neutralize Munda with repeated bombing raids and naval shelling, but the Japanese were always able to repair the airfield in short order. The Allied command thus determined that Munda had to be captured by ground troops.”

161st Infantry Regiment

“With Guadalcanal secured, attention turned to recapturing the remaining Solomon Islands, particularly the island of New Georgia where the Japanese had built a key airfield at Munda. Initially the 25th Division, now known as the Tropic Lightning Division for its swift combat actions on Guadalcanal, was not included in the invasion plans for New Georgia as resistance was anticipated to be light. However, once US forces landed on New Georgia, Japanese resistance stiffened and Corps requested a regiment from the 25th Division. The 161st was selected, landing on New Georgia on 22 July 1943, and was attached to the 37th Division.”

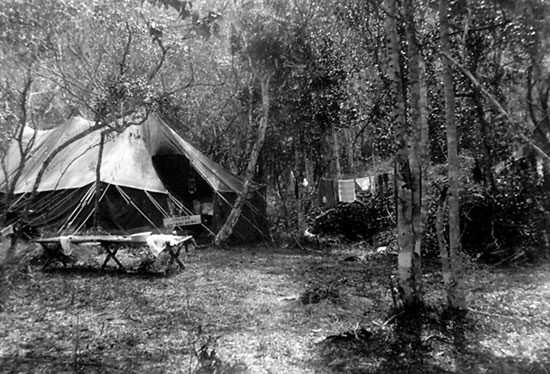

Landing on the Island

New Georgia Island is one of many found in the Solomon Island group. I landed on New Georgia in July 1943, after an initial assault by the army, and after General MacArthur had his picture taken wading ashore. The Japanese, however, were dug in and taking their toll of American soldiers.

General Douglas MacArthur wading ashore in the Philippines.

As we landed, I was struck with a momentary anxiety or fear from the smell of dank and moldy jungle growth. It brought me back to the realities of combat. I had a similar experience in New Caledonia on maneuvers when I came across a dead deer. I fell to the ground immediately as the smell of dead flesh came to my nostrils. It was an automatic reflex of self preservation. Mentally I associated various smells with battle conditions and took the first step for protection, which in this case was to hit the ground.

Army soldiers invading the New Georgia Island, July 1943.

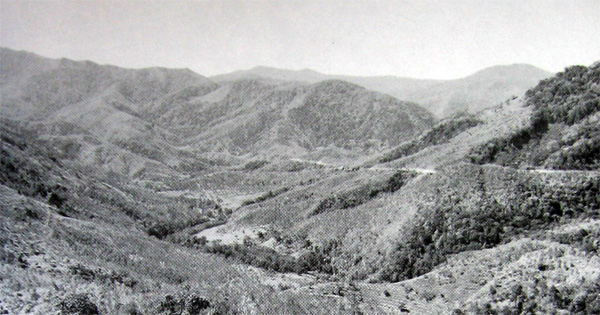

After we got ashore, however, discipline and activity took over. Our regiment pushed inland and headed for the Japanese lines. My platoon, as usual, was lead platoon. As such, I was out in front overlooking a bombed-out valley when I spotted a Japanese soldier running to their front lines. I suspected him to be a scout who had just discovered our presence and emptied a clip of ammunition at him. I didn’t see him get up.

The battalion commander seemed to get a little excited and wanted to know what was going on. He didn’t have much combat experience, and still expected those under him to get permission for every decision.

“We are at war Major,” I explained. “Mind if I shoot a few of the enemy in the process,” which ended the questions.

That evening we dug in, forming a circular perimeter of defense. During night we experienced some sniper and harassing fire as the Japanese tried to probe our defensive positions.

First Assignment

The next morning I heard my name called by my company commander. My heart started to pound, because I knew what was coming.

Evacuating casualties on New Georgia, July 12, 1943. This jeep was converted into an ambulance, capable of carrying three litters and one sitting patient.

I was ordered to take my platoon and attack from our flanks the Japanese who were in front of our positions. This necessitated circling around our own positions to the rear. To me it sounded like another Guadalcanal repeat. There was no preparatory fire—just a man-to-man confrontation like in the Civil War. The Japanese, however, had the advantage. All they had to do was wait for the sacrificial lambs. As they picked us off, the front lines could determine their position and hit them with heavy artillery.

I gathered my squad leaders around me and gave them what is known as a five-paragraph field order. This included our mission, information about the enemy, medical helps, supplies and other information they would need. As I prepared myself and my men, the initial fear left me. We left the perimeter of defense and went around to the flank where my platoon lined up for the assault.

One of my flank scouts ran over to me and reported the presence of a patrol coming in on our flank. With an upright hand, I signaled my squad leaders to wait. I walked over to the area where the patrol was reported, to warn them they were about to walk into a major crossfire area.

I had gone only 50 yards when I spotted six soldiers dressed in our uniforms and helmets. I whistled softly to them to get their attention. They appeared not to hear me, so I repeated my whistle. They turned around and looked at me. Initially I thought they were Mexicans. They all had brown eyes, and some had a few chin hairs.

Wounded in Action

My initial observation was soon dispelled, when one of them leveled his rifle at me and opened fire. I leaped forward to hit ground. As I did, a second round snapped off my helmet strap. The bullet spun around inside my helmet with such force that it snapped the helmet backward, causing it hit the back of my neck. Fragments of the bullet, I later learned, came from a high velocity dumb-dumb bullet made of aluminum, which penetrated my neck. Almost thirty years later I had an operation to repair some damage done to my spine. At the time, however, I had only one thought, which was to get out of there.

I emptied my clip of ammunition directly at the group without taking time to aim. As the enemy hit the ground, I jumped up and leaped to my rear where I was protected by a small rise in the ground. I felt a sting at the back of my neck and placed my hand over the sting. I didn’t know that I was wounded until I saw the blood on my hand. I stopped the bleeding with a compression bandage every soldier carries with him. I walked over to my platoon who, by then, had also taken cover, because the whole Japanese front line opened up on our battalion with heavy fire. We didn’t have to expose their positions.

This was no place to mess around, so I ordered my platoon to withdraw to our own lines knowing what we would find. If we stayed, we would have been caught in a massive crossfire from both sides.

Japanese Counterattack

When we approached our lines, I witnessed panic and fear from soldiers as they started to retreat from what appeared to be a desperate Japanese attempt at a last stand against the growing military might of the U.S. Army.

Japanese soldiers in the South Pacific.

A soldier ran toward me in obvious panic. I placed my rifle in his stomach, which brought him back to reality. “Where you going, soldier?” I asked him calmly. “After some ammunition,” he replied. I spotted a pile of webbed 30-caliber machine gun ammunition to his side. “There’s plenty right by you. Here, let me help you,” I said.

I placed several lengths of ammunition around his neck and motioned some of my men toward me. I placed several lengths of ammunition belting around their necks and some around my own. And then, thinking this was the right time and place—my men had never heard me swear before because of my Mormon background—I said rather firmly so all could hear: “Let’s go after these S.O.Bs.”

The Reality of War

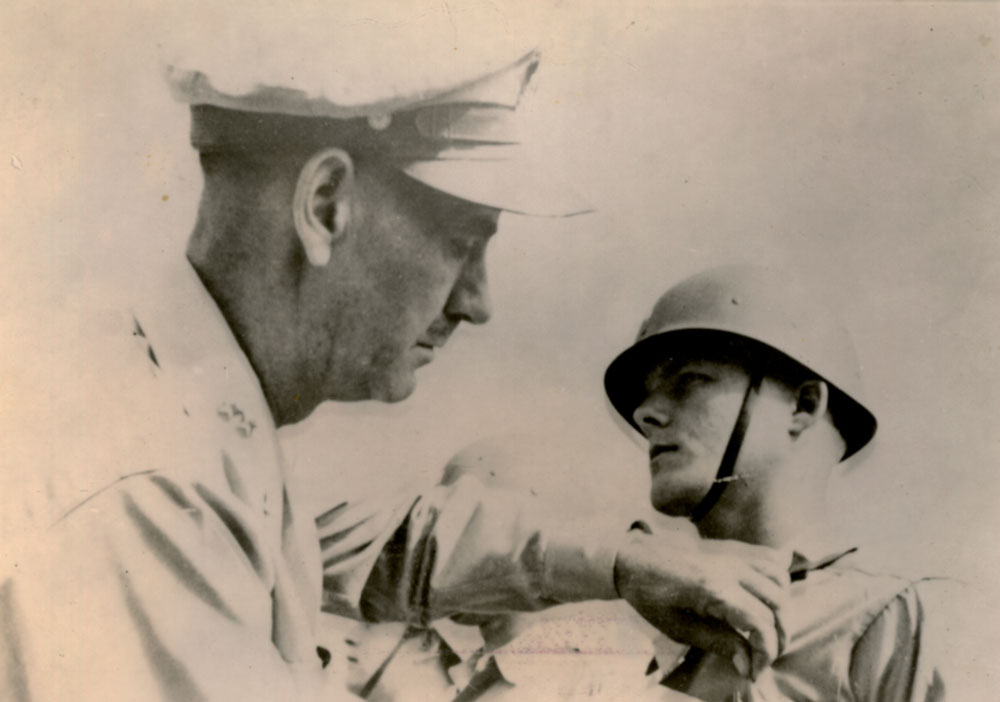

Distinguished-Service Cross

My men followed me back to our own front lines where we removed dead bodies so other soldiers could fire their weapons. I reorganized the defense and crawled back and forth to our own headquarters to arrange for defensive firepower. Soon our artillery started to land. Some shells fell short in the tall trees, and I witnessed one soldier crying in fright as he tried to dig in the ground with his hands. It was the first time I had seen a soldier cry in the process. I knew he would have to recover in some hospital for mental problems.

I reached out to one soldier who was wounded in the leg as he ran backward. He limped in a circle until he fell into one of the slit trenches. A single rifle shot from the trees made a small red hole in his forehead and silenced his pain.

A Great Compliment

Toward nightfall the enemy let up. I was tired and hungry. I had not eaten all day. One of my corporals came over to me, and paid me one of the finest compliments one man can bestow upon another in war. Somehow he had saved a can of sardines that his family had sent to him through the mail. He shared half his food with me after our own food supply was cut off because of the attack. He then said: “Lieutenant, I know you didn’t have time, so some of us have already dug a slit trench for you to lie in.” No one had ever dug my foxhole or trench before. I thanked him, ate the sardines, and slid down into the trench where I fell fast asleep. Only the rain on my body woke me momentarily, but I found that if I did not move, the water between my uniform and body would remain warm.

By morning I was sleeping in about an inch of water. When I attempted to get up, I couldn’t. My body was paralyzed from my waist up. Infection had set in from the pieces of metal in my neck. I looked up as four of my men reached down to lift me out of my foxhold. They knew I was in trouble.

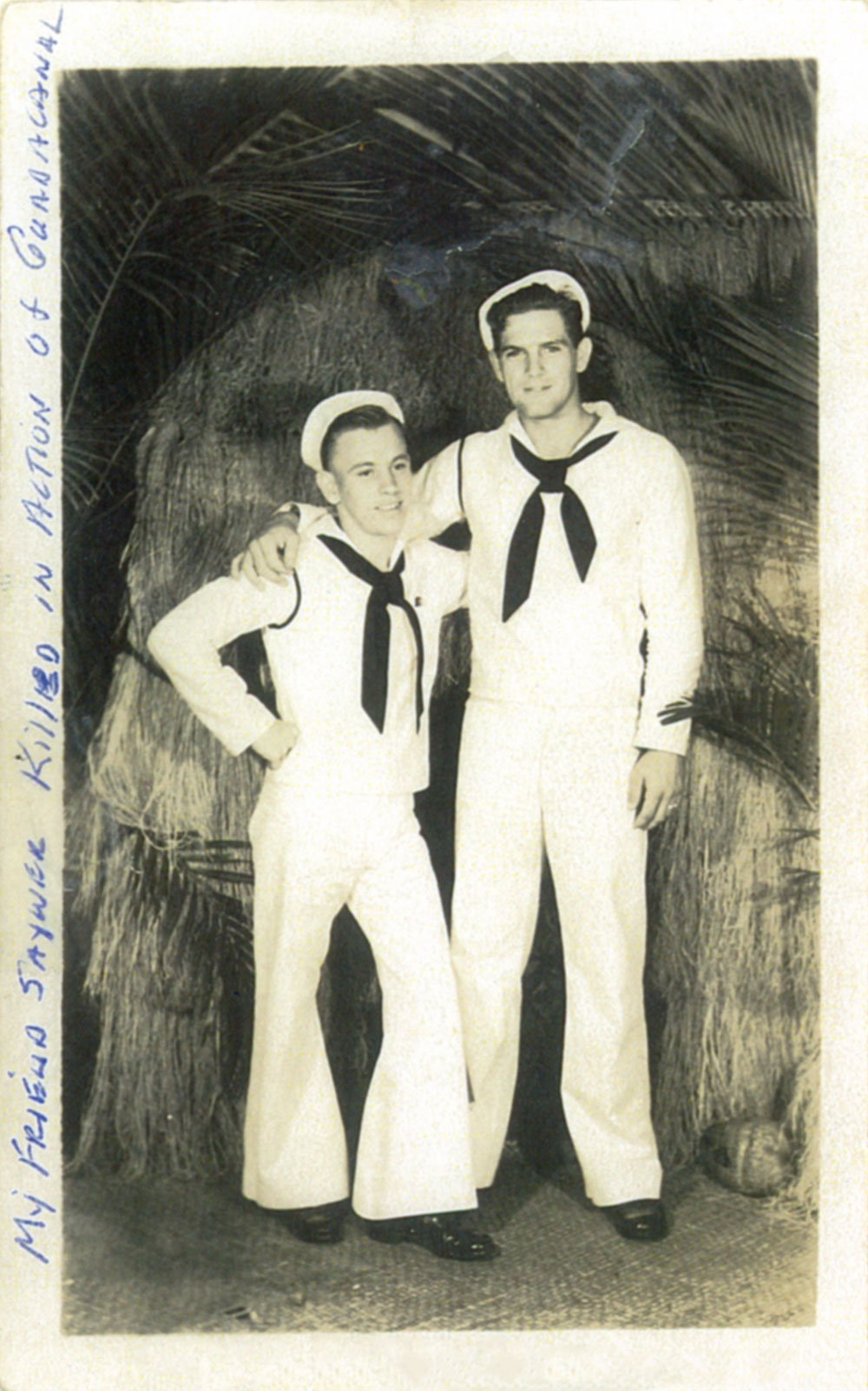

Friend Is Killed

Japanese fire power had subsided, and our artillery had taken its toll. As I walked toward the aid station to our rear with the help of my men, a friend from another battalion came toward me on the trail. I asked him if he had any contact with Fred Scheunman. Fred and I were the only Mormons in the regiment and had come to be good friends. We met when we were at Fort Benning in Georgia. Here in the Pacific we served in different battalions so didn’t get to see each other very often.

Soldiers taking cover from Japanese machine gun fire.

I soon learned that his battalion was also attacked. Fred was shot down with a machine gun burst while leading his platoon against a Japanese position, just on the other side of our battalion defenses. Fred was married only two weeks before entering the army, and a good man. When he was on leave in Hawaii, he would send flowers to both his wife and my girl friend Dorothy. I did the same when I was on leave. I learned later that Fred’s death and my wound completed the list of casualties from Fort Benning’s class of ‘39, which was 100 percent. This class graduated almost 200 “Ninety-Day Wonders,” of which I was one.

Because of my wound, I was evacuated to New Caledonia on a flat-bottomed ship the Navy called an LST, and put in a hospital. After a few weeks I received orders to return to New Georgia.

Friend Is Wounded

Years later I was reminded of how lethal and damaging a conventional war can be. I received a letter from one of my former squad leaders, Sergeant Keifer, who told me what happened to him on the island of New Georgia. “You wanted to know how I got hit,” he responded to one of my questions. “I was told that we were on the side of a hill just beyond the Munda Airfield [probably Bibilo Hill]. I was evacuated back to Jackson, Mississippi, and later to Battle Creek, Michigan, after spending time in New Caledonia and New Hebrides. I was in bed for 22 months and had back surgery in ‘53 and ‘68. In January ‘83 I had a total left knee replacement.” He continued, sharing some of his feelings: “A number of lives have been really torn up by the war, so I figure I’m really lucky.”

.jpg)